The Photographers Who Captured a World of Play on New York City’s Streets

Explore how images from the Brooklyn Museum’s photography collection reveal the playscape of New York City children.

by Imani Williford

December 13, 2024

Brooklyn Snapshots

Brooklyn Snapshots is a column that uncovers stories within the Brooklyn Museum’s Photography collection.

Growing up in New York City provides an unofficial second education. As historian Deborah Dash Moore notes, “urban living fosters a sense of awareness about people and place.” Between the Great Depression and the mid-20th century, a generation of street photographers applied knowledge from this “second education” to their images, many of which center on children. These works are part of a tradition of street photography that spotlights childhood playtime on the streets and sidewalks of New York City—a tradition we can trace through images in the Brooklyn Museum’s collection.

Several of these artists were members of the Photo League (1936–51), a photography cooperative founded by Sid Grossman and Sol Libsohn. This cooperative aimed to reject the exclusive and bourgeois notions of photography that dominated magazines in the 1930s and to make photography a democratic, progressive, and socially conscious art form. These values would inspire generations of photographers to follow.

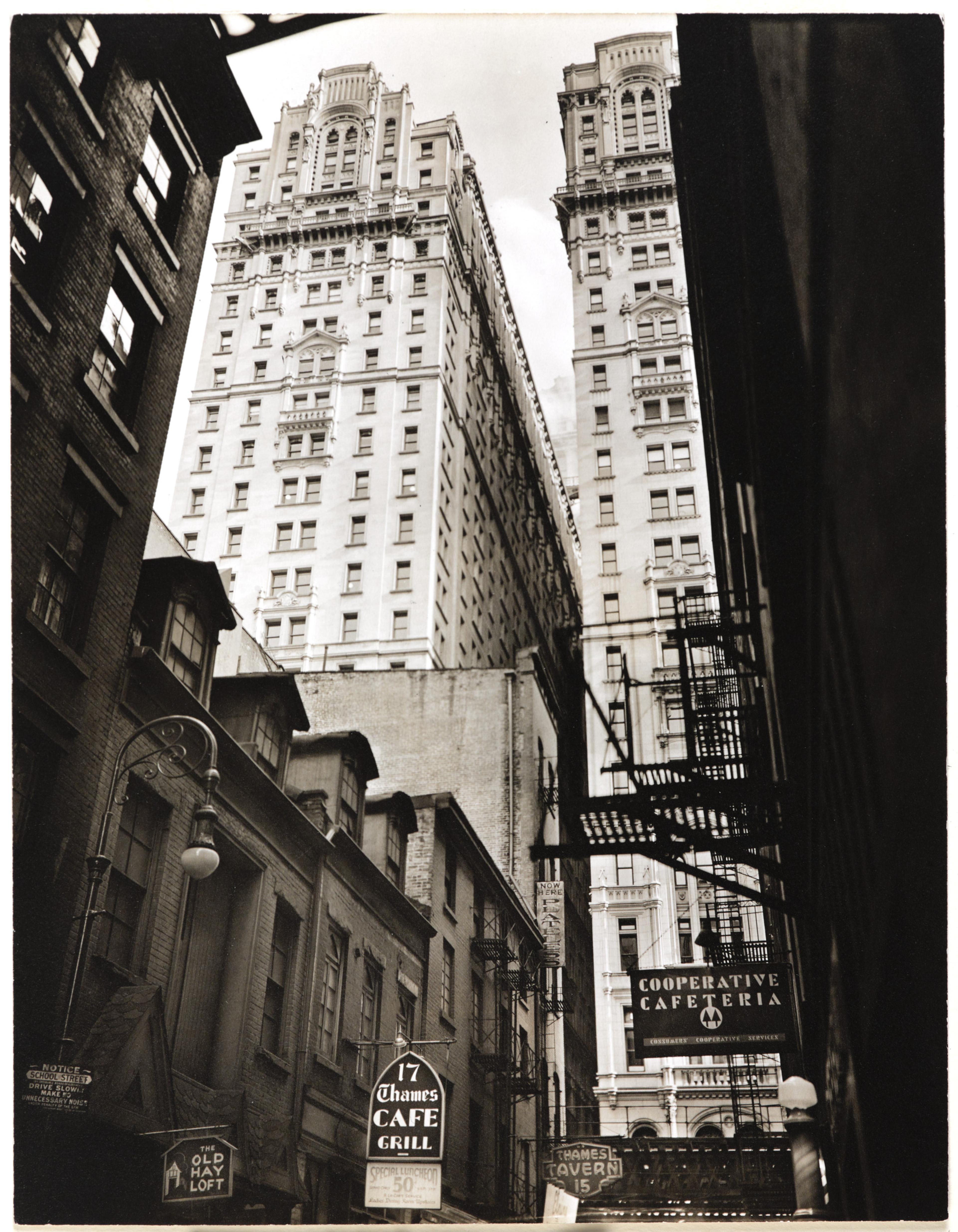

Portrayals of the city and the children

Despite the Depression, New York City’s urban landscape flourished in the 1920s and ’30s with the construction of the Chrysler and Empire State Buildings as well as the newly overhauled subway system. Still, New Yorkers, many packed in tenements, faced economic uncertainty and unstable race relations. Members of the Photo League expressed unease about the portrayal of the city in the upcoming 1939 World’s Fair; they wanted their fellow Americans to see New York City as a place with “problems and possibilities,” Dash Moore writes in Walkers in the City: Jewish Street Photographers of Midcentury New York . In their authentic documentation of the streets, these New Yorkers seized some control over their city’s image, by providing “social solidarity and cultural communication rather than false images and stereotypes” found in popular media.

But why did they often focus on children? American culture in the 1930s and ’40s was saturated with child-conscious media, activities, and study. Child actors such as Shirley Temple and Mickey Rooney were box office stars. The Hardy Boys and Nancy Drew book series were popular staples of children’s literature. In an essay for the Museum of Modern Art’s 1981 exhibition American Children , Susan Kismaric observed that postwar economic and population changes also contributed to the country’s newfound focus on children. The combination of the baby boom and economic prosperity emphasized the role of family by encouraging Americans to spend money on activities such as graduations, communions, birthday parties, and other familial gatherings.

Moreover, the field of child psychology had expanded greatly with contributions from Anna Freud and Melanie Klein; consequently, the topic of child psychology was circulated in the popular press. Dr. Benjamin Spock’s Baby and Child Care (1946) sold 500,000 copies in its first six months, which grew to a million copies in a year; it ended up becoming one of the best-selling books of all time. These elements—New York street smarts, a socially conscious mindset, and a child-focused public—created a recipe for a distinct form of documentary photography that centered urban childhood as a form of solidarity and shared experience.

Aaron Siskind

Public school teacher Aaron Siskind joined the Photo League in 1936 and helmed “The Harlem Document ” (1932–40). This collaborative project between Siskind, other Photo League photographers, the Federal Writers Project , and Black sociologist Michael Carter represented Harlem residents in their domestic life, work life, and social organizations.

Siskind also photographed Harlem children at play. In Wishing Tree, three boys surround a tree stump; one boy looks on as a girl stands against a pole and faces Siskind’s camera. Wedged on an island between two streets, the boys’ eyes are obscured from the viewer as they study the stump and its endless narrative possibilities. Siskind’s photograph calls attention to the lives of Harlem’s youngest residents as they carve out a space for themselves.

Arthur Leipzig and Walter Rosenblum

When Photo League member Arthur Leipzig saw a print of Renaissance painter Pieter Bruegel’s Children’s Games (1560), he was amazed at the similarities between children’s games played in 1940s New York and in 14th-century Flanders. The work inspired a new Children’s Games (1943), Leipzig’s first major photography essay, and sparked a long-standing interest in capturing youthful leisure against an urban backdrop.

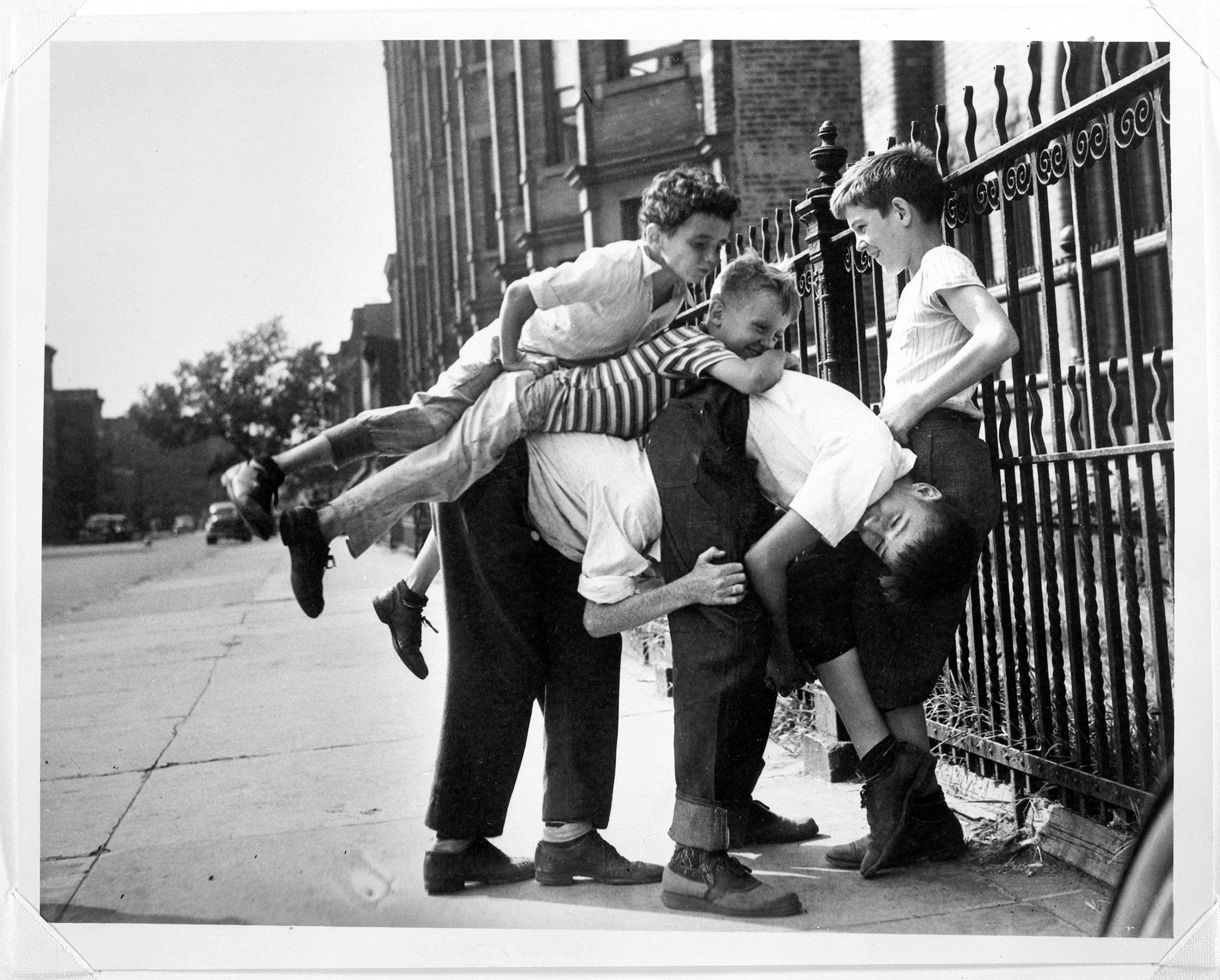

In Rover, Red Rover, four children smile and laugh while playing the titular game. Leipzig foregrounds the children as the point of action and emotional tenor on an otherwise unremarkable New York City corner. With their arms linked and the sun shining on them, the children’s fluidity counters the rigidity of the buildings, cars, and adults in the background. Similarly, in Johnny on the Pony, a group of boys piled atop each other mimics the sidewalk’s bricks and blocks, albeit in a disorderly and playful manner. Photographing Children’s Games allowed Leipzig to capture New York’s youngest citizens exercising control over the city’s domineering landscape.

At this time in New York City’s history, the streets were, as Leipzig wrote in his 1995 book Growing Up in New York, “the living rooms and the playgrounds, particularly for the poor whose crowded tenements left little room for play. The children occupied the streets, now and then allowing a car or truck to pass.” This is illustrated in Tops, in which two boys play with spinning tops on a street as a woman walks past them. Leipzig angled his camera to reveal an expansive view of a city block with plenty of territory left to conquer. The angle also makes the boys look larger than they would at eye level; they appear nearly the same height as the woman walking by. From this point of view, Leipzig stresses their command of the street.

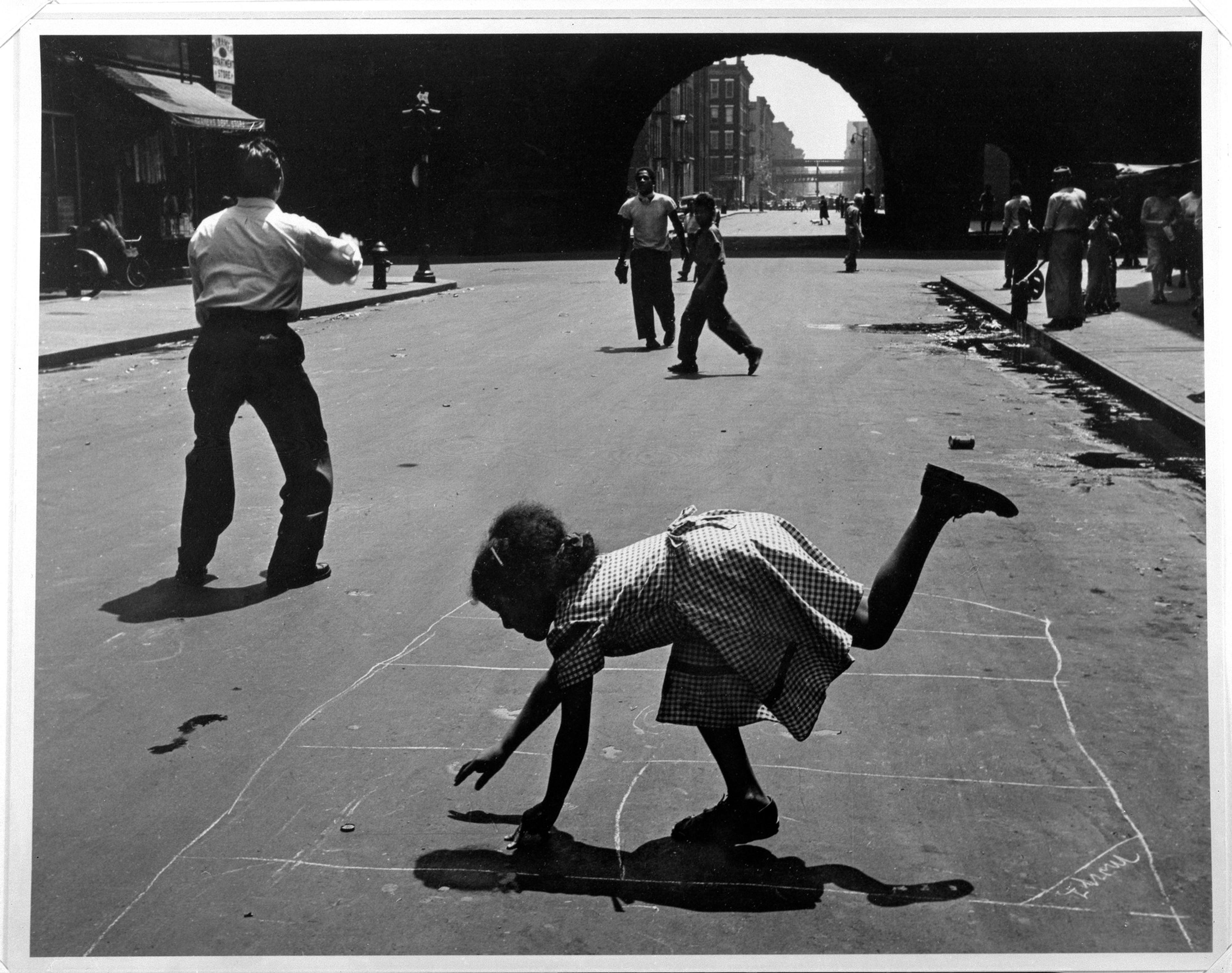

Photo League member Walter Rosenblum similarly frames the streets as a place of limitless possibilities for children. In Hopscotch. 105th St., New York, Rosenblum directs his camera to foreground a girl playing hopscotch in front of a game of catch. Much like Leipzig’s Tops, Rosenblum’s viewpoint prompts us to look at the vast slab of asphalt, untouched by cars, as imbued with great potential for playtime. His camerawork also puts the viewer just slightly above the hopscotching girl, inviting them to engage with a child’s perspective.

Leipzig continues this exploration of youth street dominance in Stickball. The photograph features a group of youngsters playing a game of stickball, a variation on baseball which, as Leipzig notes in Growing Up in New York, displayed the creativity of New York’s youth: “They played games that had been handed down for generations, as well as others they made up. If one kid had a ball, someone else found a bat—a broomstick or a piece of wood.” The main group takes up the street in a range of motions, including hitting, catching, sitting, and standing, while two other kids prepare to cross the street and a butcher stands outside a chicken market, looking away from the camera.

As Dash Moore writes, these photographers often captured interracial play to magnify the “social interactions across ethnic and racial boundaries” that local neighborhoods produced. Stickball shows the activities and energies that can coexist in the street, underscoring the significance of street play as a place to develop social codes and rules.

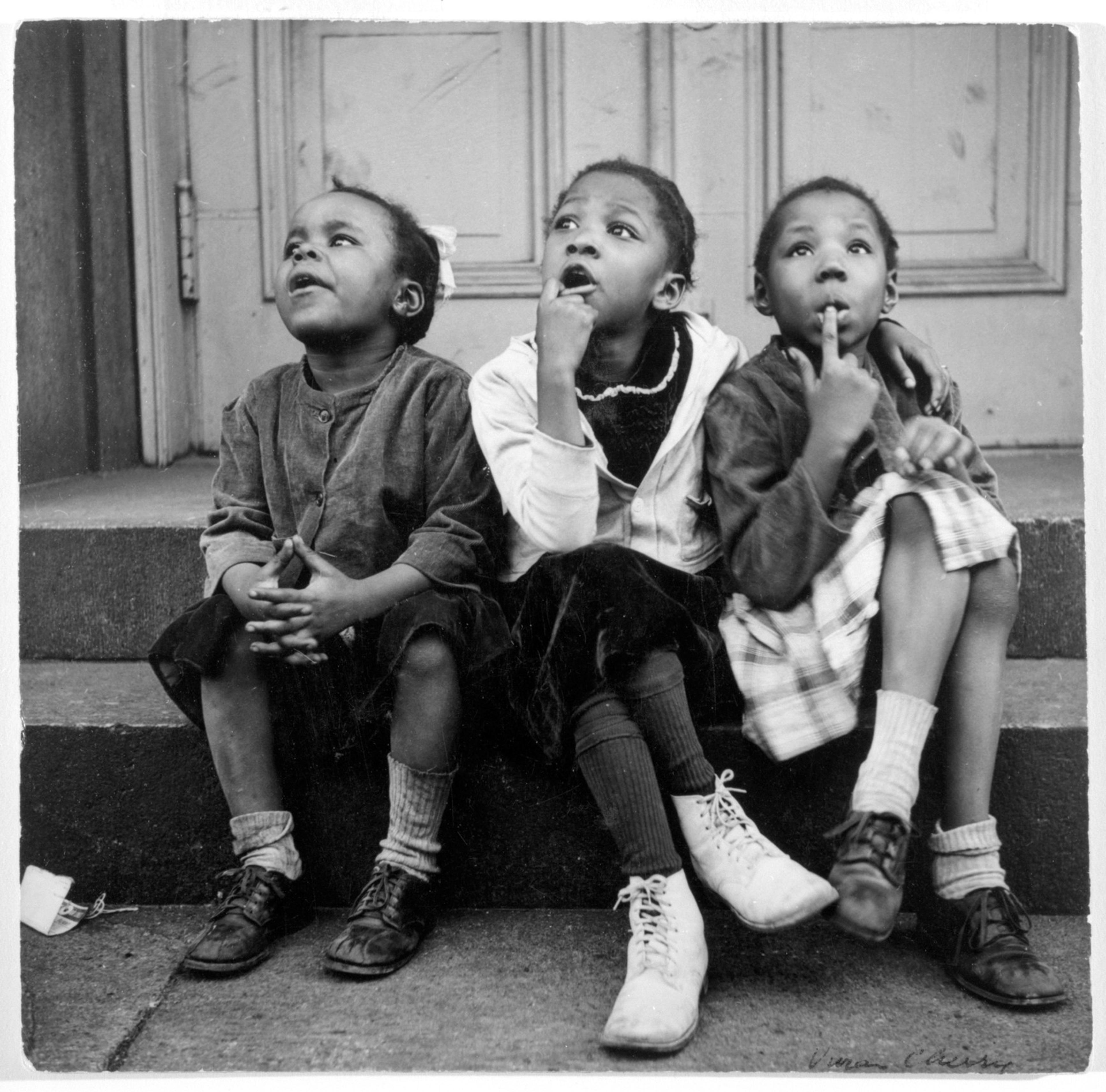

Vivian Cherry

Photographer Vivian Cherry joined the Photo League in the late 1940s. Initially a Broadway and nightclub dancer, Cherry became a photographer after working as a darkroom technician. In Harlem, Watching a Sky Writing Plane, Cherry’s experience with performance shows as she directs our attention to the three girls, who are as attentive as an audience watching a show. Sitting on a step in scuffed shoes, with trash on the corner and a dirty door behind them—the girls stare upward; their eyes reveal that each girl is engrossed by a distinct part of the skywriting. The photograph echoes Siskind’s Wishing Tree in that the children are transfixed in wonder.

In [Untitled] (Buddy Tomatoes—Three Boys Playing Cops and Robbers), two boys play with toy guns, one of them pointing his play weapon at a third boy who stares down its barrel. The photograph shows a disturbing side of playtime while calling attention to the influences of film and news on children’s daily lives, as Cherry points out in the book Helluva Town: New York City in the 1940s and 50s . Whereas in Stickball, Leipzig emphasizes children’s ability to create their own social environment, Cherry’s photograph reveals how children’s games can mirror societal conflict.

Garry Winogrand

Garry Winogrand was slightly younger than the Photo League photographers, but his work reveals league-like approaches. Winogrand started his career in photojournalism and advertising during the 1950s but eventually renounced that work because he felt both forms “were designed to manipulate the audience,” as noted in the book Public Relations . During the 1960s, Winogrand began to shift his focus to documenting candid moments of everyday life.

In his photograph New York City, NY, two girls play a hand game on a sidewalk as two women and another child hail taxis. This photograph is strikingly different from the earlier era of childhood street photography: Winogrand removes us from lower-income neighborhoods with tenements and brownstones and takes us to a commercial street in Manhattan surrounded by skyscrapers. In previous photographs, open streets illustrate a sense of possibility; here they evoke a ghost town, marking the absence of life that elsewhere characterizes the space.

Similar to Cherry, Winogrand comments on the relationship between adults and children. A closer look shows that the child standing between the two women mimics their gestures of hailing the cab. With the young girls and women differing in hand gestures and even sidewalk colors, the photograph highlights children’s ability to create their own space, even as they are influenced by adults.

Helen Levitt

Though photographer Helen Levitt was not an official member of the Photo League, she socialized there, exhibited her works in league shows, and shared its left-leaning politics. She began her career as a teenage darkroom assistant. In Helen Levitt: New York , the artist is quoted as saying that she was initially drawn to taking photographs of children’s chalk drawings and graffiti, as well as people on the street in the warm weather.

Boy with Bubble actually depicts two boys. One, dressed in a button-down shirt with a jacket, carefully holds a soap bubble. He is out of focus, and we are unable to see the details of his eyes or the unidentifiable object (possibly a cigarette) hanging from his mouth. The other boy—shot in focus, wearing a wrinkled and stained shirt, and with black sludge smeared on his face—is fixated on the bubble.

While Levitt’s photograph is in color—distinct from the black-and-white examples we’ve seen from her peers—it too emphasizes the children’s viewpoint. However, as writer Shamoon Zamir notes in Helen Levitt: New York, Levitt liked to document “ambiguous actions” between people, whereas the other photographs’ titles tend to reveal the game or activity they portray. With focus manipulation, cropping, and vague subject matter, Levitt creates a cramped and uncertain perspective.

Similar to Cherry and Winogrand, Levitt emphasizes the ways adult influences seep into children’s worlds. But unlike the gleeful and eternal images by Photo League members, Levitt’s photograph foreshadows the ominous world of adulthood that will inevitably replace childhood innocence.

Imani Williford is Curatorial Assistant of Photography, Fashion, and Material Culture at the Brooklyn Museum.