The Allure and Darkness of Coney Island on Film

Explore Coney Island through historic photographs in the Brooklyn Museum’s collection.

by Imani Williford

June 4, 2024

Embedded along the southwestern tip of Brooklyn’s shoreline is Coney Island. This jewel of enchantment has nourished generations of New Yorkers’ appetite for escapism and wonderment with dizzying rides, entertaining games, and a shimmering beach. Also brewing within this coastal fairyland are elements that prey on its visitors’ fears and anxieties: taunting fortune tellers, unnerving haunted houses, and looming tides of unknown waters.

The Brooklyn Museum’s Photography collection includes more than 200 photographs of Coney Island, which document one of the borough’s most iconic landmarks as it has balanced states of bleakness and bliss. The photographs reflect the ways that Coney Island is a microcosm of the national mood as well as a community unto itself, maintaining its essence through bonds of affection and camaraderie.

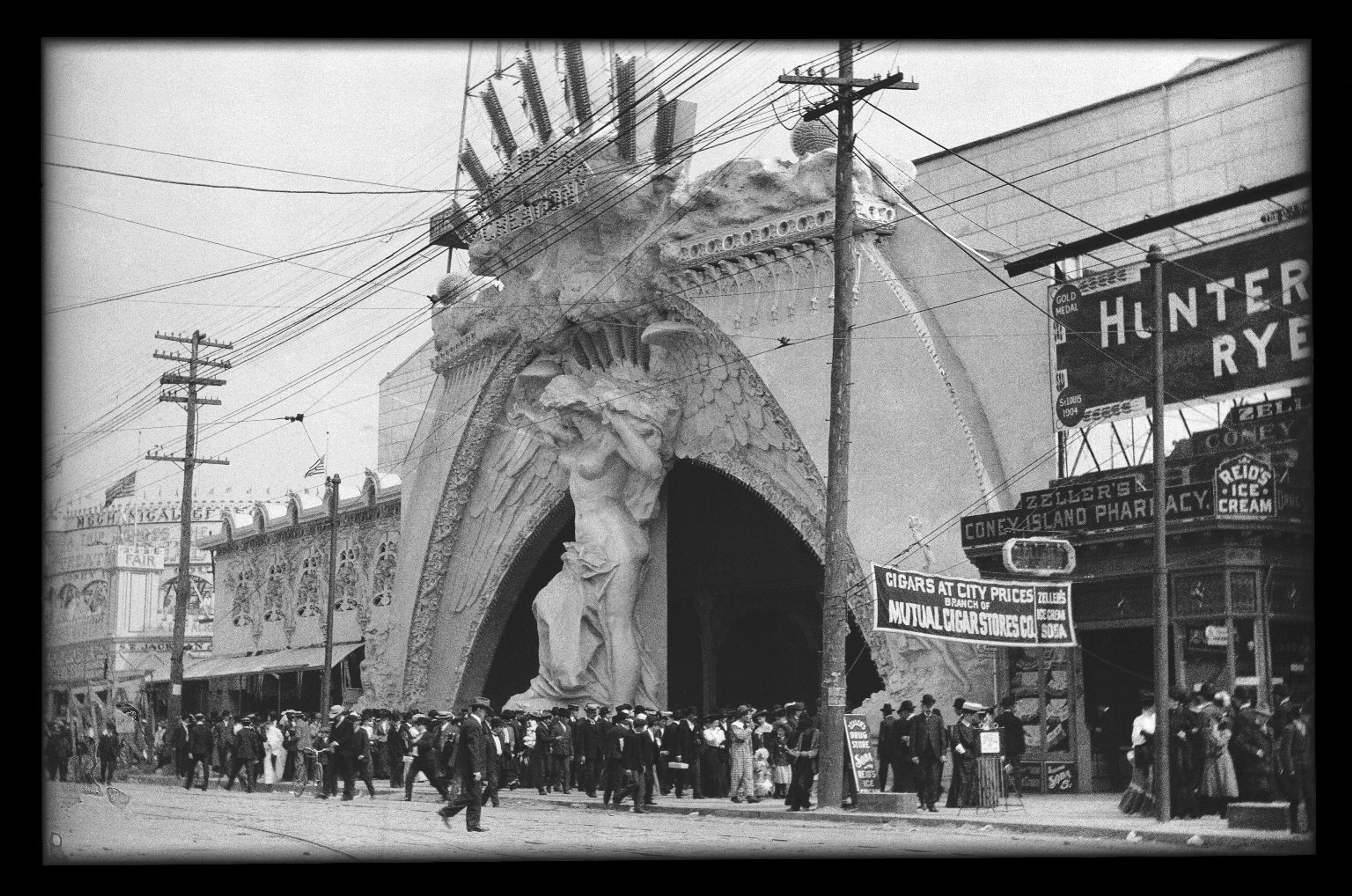

From the late 1800s to the mid-1960s, Coney Island’s iconic boardwalk was made up of a cluster of small amusement parks competing for visitors along Surf Avenue. These parks included Dreamland (1904–11), Luna Park (1903–46), and Steeplechase (1897–1907, 1908–64). Early photographs show the parks as hives of activity, drawing in crowds with dueling fantasies of delight.

The original Steeplechase was a family-friendly park featuring manicured gardens, a Venice-themed boat ride, and the largest ballroom in New York State. The year after half the park was destroyed in a 1907 fire, it reopened in a two-acre, weatherproof glass pavilion that featured a mechanical horse race and a three-tiered carousel. Dreamland was a refined and orderly park, with sterile white buildings (including a 375-foot tower), a Japanese tea pavilion, and a catastrophe rescue ride called Hellgate where riders could watch a simulation of tenements burning and tenants being rescued.

Luna Park was known for its colorful lights and a circus, which included camels and elephants that walked the grounds. The park also featured Trip to the Moon, a simulation ride that allowed visitors to land on a green cheese-like surface by riding a cigar-shaped “aircraft” fitted with motion simulators, propellers, and wings. These amusement parks planted seeds of experiences that would shape generational understandings of Coney Island as a destination for exuberance on Brooklyn’s ocean shore.

This sentiment of delight continues in the postwar photograph Modern Venus of 1947, Coney Island, in which a young beauty-contest winner rides Coney Island’s famous Parachute Jump. Wearing a two-piece bathing suit accessorized with a tiara and sash, she mirrors the glamorous image of swimmer and screen siren Esther Willams, known for her films Bathing Beauty and Thrill of a Romance. The woman’s sleek veneer radiates as she grips the ride’s rope in order to gracefully wave at the sea of people below.

Placing this symbol of beauty and modernity on the Parachute Jump provides insight into America’s postwar spirit. The Parachute Jump had debuted at the 1939 World’s Fair, which began on April 30, just a few months before Germany’s invasion of Poland initiated World War II. The fair emphasized optimism about the future with slogans “The World of Tomorrow” and “Dawn of a New Day,” along with the many technological and architectural inventions it exhibited. The Jump, which mimicked simulators used for paratroopers, exemplified this idealism as the tallest structure at the fair.

The fair ended in 1940, and the next year the Jump was relocated to Steeplechase, where it ushered in a renewed era. Built on the site of another fire, this one in 1939, the ride’s arrival came in the midst of a wartime renaissance for Coney Island. Even as it experienced effects of the war—including blackouts that significantly reduced amusement park lighting, the shutdown of shooting galleries due to ammunition shortages, and canceled beauty contests and other events—Coney Island had a slew of patriotic and war-themed attractions that drew millions. These included a ball-toss that featured caricatures of Hitler and Hirohito, a show called “Axis Atrocities” on the Coney Island Bowery, and, in 1943, a “Back the Attack”–themed carnival and parade that doubled as a war bond drive. Coney Island had additional appeal for residents of New York and nearby states as gas rations restricted long-distance travel. A record 46 million visitors came to Coney Island in 1943, the largest number since 1926. The neighborhood also became a popular spot for the troops, offering cheap rides, big-band clubs, and photo studios with discounted rates for Coast Guard members (at their insistence).

While the Parachute Jump achieved mixed success—it didn’t work on windy days, and the cables would often get tangled, requiring intense rescue efforts—its presence declared the nation’s determination to pursue great heights in the face of an uncertain future. Gripping the Parachute Jump—akin to a scepter or flag—the “Modern Venus of 1947” signifies America’s restored sense of normalcy, return to order, and fresh prosperity two years after World War II.

Taken two decades later, photographs by Stephen Salmieri (American, born 1945) spotlight more conventional elements of life in Coney Island.

An empty roller coaster stands out against a cloudy sky. A woman dressed in a coat, a hat, and a pair of boots lingers on a boardwalk devoid of its usual throngs of people. A group of boys fishes from a rock jetty, with no visual emblems connecting them to Coney Island. There are empty ticket booths, locked-up rides, and fortune tellers waiting in piecemeal, dilapidated booths surrounded by trash. Salmieri’s photography upends the promise of Coney Island’s “dreamland,” instead framing it as a ghost town haunted by those who feed off the morsels of its glory days.

This sensibility is echoed in Sebastian Milito’s photograph Boy in Fur Coat - Coney Island. Shot a year after the Vietnam War ended, Milito’s photograph pulls away from the iconic Parachute Jump—now a skeleton of its former self after it ceased operating in the 1960s—and brings our attention to a sparse Coney Island beach. Milito focuses on a young man standing on a rock and dressed in a long fur coat, flared pants, and platform boots, details that reference the neighborhood’s colder off-season. This contrast to Modern Venus conveys the widespread feelings of despair and deficiency that followed the Vietnam War.

Yet a spirit of solidarity runs through Coney Island amid the booms and busts. Founded in 1903, the Coney Island Polar Bear Club claims to be the “oldest winter bathing club in the United States .” Salmieri’s 1981 photograph of the club shows a group of bathers and onlookers gleefully posing on the snowy beach—an intergenerational declaration of continuity in a place that fluctuates between myth and the material world.

Unity is also underscored in Victor Friedman’s Three Women and Flag, Coney Island. The image shows three older women smiling and supporting each other, with the American flag waving behind them. Their age and unified stance characterize the perseverance of Coney Island’s community.

The Hug: Closed Eyes and Smile by Harvey Stein (American, born 1941) similarly shows people cultivating a sense of belonging in Coney Island’s evolving environment. The photograph captures two people embracing on the beach with the Parachute Jump in the background, an image that balances the optimism of Modern Venus with the desolation of Boy in Fur Coat. The beach is sparsely occupied despite the obvious good weather (as evidenced by the swimming attire and sun hat worn by one of the subjects and people in the background). Unbothered by Coney Island’s decay, the central pair embrace as a hand reaches to them from outside the frame, an invitation to further connect.

One of the few color photographs of Coney Island in the Museum’s collection comes from Lynn Hyman Butler’s series Coney Island Kaleidoscope. The series comprises photographs of Coney Island in color and motion. The Gossips shows two sets of friends walking along the boardwalk, talking and lugging their belongings to or from the beach.

Butler (American, born 1953) immerses the beachgoers in a colorful haze, creating an aura of disorientation. The intensity and vigor of the image foregrounds Coney Island’s uncertain history, an intrinsic part of its atmosphere, while highlighting the groundedness that comes from the community of this storied neighborhood.

Read more about Coney Island’s history in the sources that informed this piece.

Charleston, Beth Duncuff. “The Bikini.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. Last modified October 2004. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/biki/hd_biki.htm .

Denson, Charles. Coney Island: Lost and Found. Berkeley: Ten Speed Press, 2004.

Homeberger, Eric. The Historical Atlas of New York City: A Visual Celebration of 400 Years of New York City’s History. New York: Holt Paperbacks, 2004.

Immerso, Michael. Coney Island: The People’s Playground. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2002.

“Welcome to the Fair! The 1939 and 1964 New York World’s Fairs.” New York State Library, July–August 2014. https://www.nysl.nysed.gov/collections/worldsfair/ .

Imani Williford is Curatorial Assistant of Photography, Fashion, and Material Culture at the Brooklyn Museum Brooklyn Museum.