In Museums, Are Frames Part of the Art?

Find out how paintings in the Brooklyn Museum collection get their frames.

by Elizabeth Treptow

August 19, 2024

Frequent Art Questions

Asked and answered: Frequent Art Questions is a series that addresses frequently asked questions from Brooklyn Museum visitors about art and museum practices.

In art museums, paintings are often displayed in frames. Are all frames part of the artworks? Are they original to the paintings? The answers vary depending on the art and the institution, but we can shed some light on frames in the Brooklyn Museum's collection.

Usually made of a wooden base with varying levels of ornamentation, frames have been a common feature of European and American paintings since at least the Renaissance era. In this tradition, frames can be likened to furniture: they both protect the painting and provide a transition between the image within and the room beyond.

Gilding and silvering have been common throughout much of the history of framing. In addition to demonstrating wealth, these embellishments reflect light, which helped to illuminate dark interiors and even the paintings themselves before the widespread use of electricity.

Popular styles of frames have evolved over time. Early frames mirrored the architecture of the buildings in which the paintings were displayed. Zanobi Strozzi’s Virgin and Child with Four Angels and the Redeemer is in its original frame, which dates to about 1450 and is the oldest of its kind in New York City. The columns at the sides and triangular pediment at the top echo Roman architecture that Renaissance artists looked to for inspiration.

Virgin and Child’s frame is a rare exception: the majority of frames you see in the Museum are not original. Most paintings come with a frame of some sort, but they usually are not appropriate to the painting’s original context. Collectors often have replaced frames to suit their own tastes. Framers, conservators, and curators thus work together to select new frames before the painting is hung in the galleries.

The portrait of Doña María de los Dolores Gutiérrez del Mazo y Pérez was painted in Puerto Rico around 1796; it was acquired by the Brooklyn Museum in 2012. The original frame was long gone, so Museum staff selected one that would match. Even in overseas colonies, far from the royal courts of Europe, the elaborate imagery attached to the top of this frame would have been customary at the time.

Like painting styles, frame styles gradually became increasingly ornate, featuring more and more ornamentation carved from wood or sculpted in plaster. Sculptural frames reached their most ostentatious in the 18th century, especially for portraits.

In the 19th century, frames began to be mass-produced in styles that looked to the past for inspiration. These revival styles were also popular in furniture and architecture. Thanks to extensive documentation on Gilbert Stuart’s 1796 portrait of George Washington, we know that the painting’s current frame (its third one) was purchased in 1856. This custom frame incorporates Greco-Roman elements, such as the acanthus leaves on the interior band and the crossed straps on the convex band—which echo the fasces on the furniture legs depicted in the painting.

Later in the 19th century and into the 20th century, radical innovations in painting called for new approaches to framing. The famously meticulous Claude Monet often carefully selected historical frames—sometimes already 200 years old—for his finished paintings. Monet’s original selection for The Doge’s Palace (top), however, does not survive. In 2001, the Museum commissioned a brand-new frame for the work. Produced by Bark Frameworks , the new design complements the painting by recreating the texture of the water.

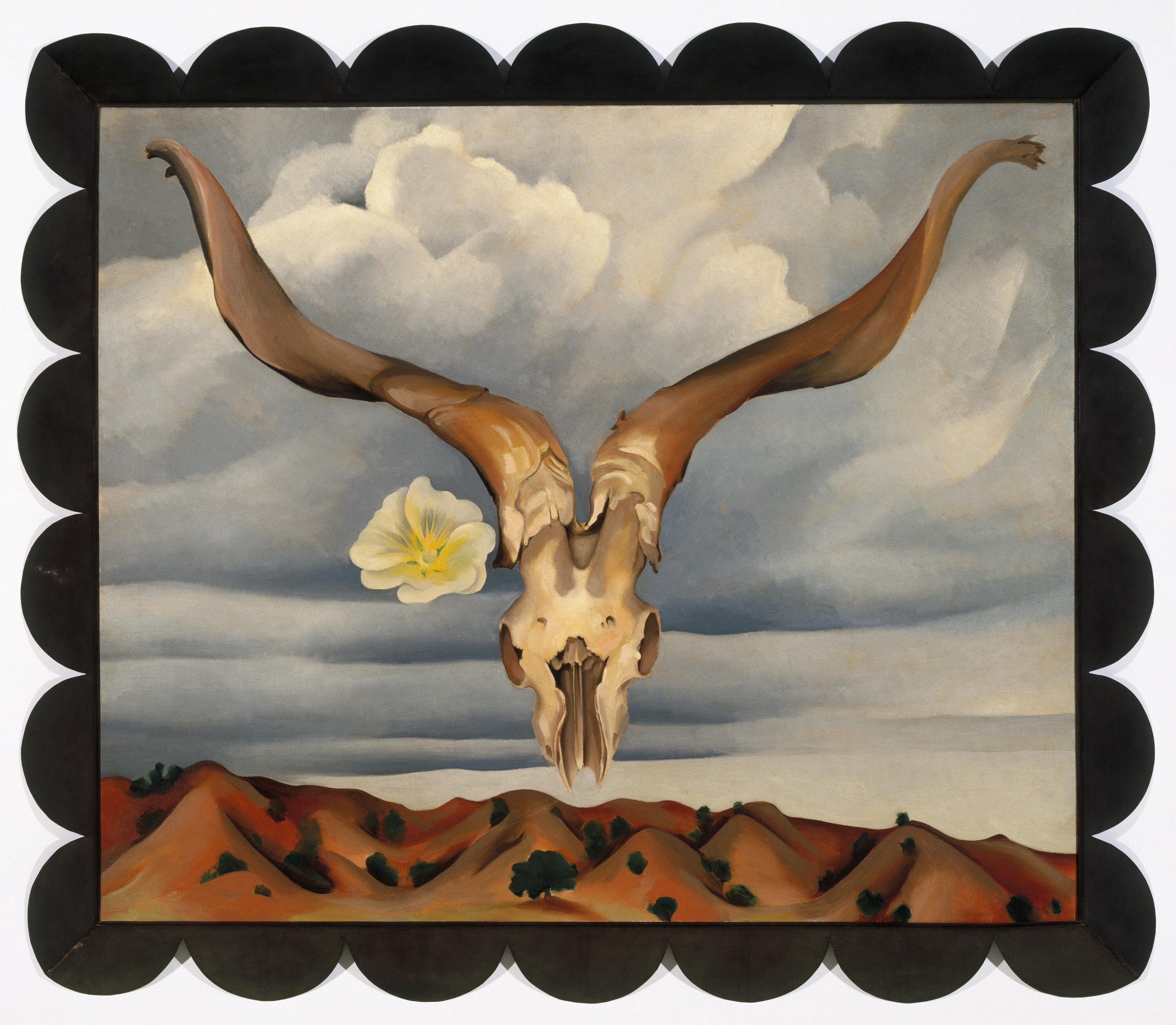

Monet wasn’t the only artist with opinions about frames. Florine Stettheimer personally selected the frame you see around Heat. Georgia O’Keeffe worked closely with framer George Of to create unique frames to complement many of her works, including Ram’s Head, White Hollyhock-Hills. Though fascinating, this frame is quite delicate, so sometimes the painting appears in a simpler frame suitable for travel.

In recent decades, many painters have preferred for their work to remain unframed. But some contemporary artists continue to take a deep interest in frames. The specially designed frame for Kehide Wiley’s Napoleon Leading the Army over the Alps is considered part of the artwork and a direct reference to 18th-century styles.

Today, photographs and prints are often shown in frames with very minimal designs, but even these plain frames can carry a message. For María Magdalena Campos-Pons’s 2023 exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum, mahogany frames were made for the photo series Voyeurs and Beholders of . . ., symbolizing the exploitation of the Caribbean by European imperialism. While artworks have varying relationships to their frames, frames can be considered works of art in and of themselves.

Elizabeth Treptow is a Digital Content Producer at the Brooklyn Museum. Special thanks to Associate Paintings Conservator Lauren Bradley, Assistant Paintings Conservator Ellen Nigro, and Framer Takayuki Umezawa.

More from this series

- Frequent Art Questions

Why Are the Noses Broken on So Many Ancient Egyptian Statues?

By: Elizabeth TreptowAncient texts provide a few clues.

- Frequent Art Questions

When Artists Make Multiples, Which One is “Real”?

By: Elizabeth TreptowExplore several artworks in the Brooklyn Museum collection and learn why they look just like other works you may have seen.

- Frequent Art Questions

How an Ancient Egyptian Blue Has Survived for Thousands of Years

By: Elizabeth TreptowThis brilliant shade of blue unlocks a history of Egyptian glazing technique.