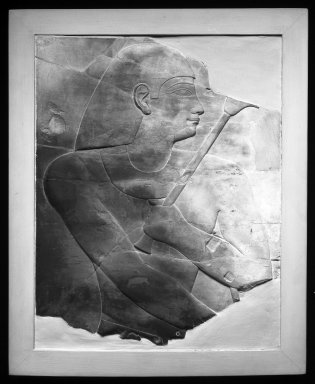

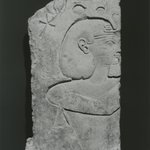

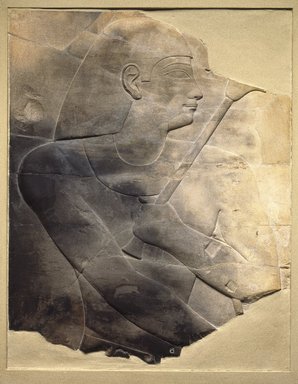

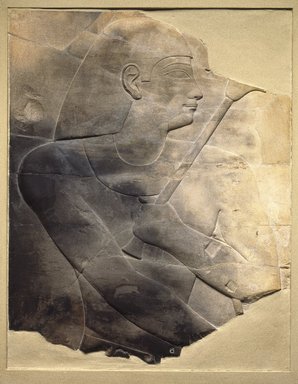

Egyptian. Raised Relief of Montuemhat(?), ca. 670–650 B.C.E. Limestone, 14 15/16 x 12 in. (38 x 30.5 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Bequest of Mrs. Carl L. Selden, 1996.146.3. Creative Commons-BY (Photo: Brooklyn Museum, 1996.146.3_SL1.jpg)

Raised Relief of Montuemhat(?)

Egyptian, Classical, Ancient Near Eastern Art

On View: 19th Dynasty to Roman Period, Martha A. and Robert S. Rubin Gallery, 3rd Floor

As perhaps the most powerful official of his time in southern Egypt, Montuemhat had one of the largest and most lavishly decorated nonroyal tombs known. Although this relief is probably of the man himself, it is not a portrait. Rather, It is an idealizing, archalzing image reflecting the style of Theban works of Dynasty XVIII and possibly also the Middle Kingdom. The fortuitous blackening of the relief's surface is the result of a burning of unknown date.

CULTURE

Egyptian

MEDIUM

Limestone

DATES

ca. 670–650 B.C.E.

DYNASTY

late Dynasty 25 to early Dynasty 26

PERIOD

Late Third Intermediate Period to early Late Period

DIMENSIONS

14 15/16 x 12 in. (38 x 30.5 cm) (show scale)

COLLECTIONS

Egyptian, Classical, Ancient Near Eastern Art

ACCESSION NUMBER

1996.146.3

CREDIT LINE

Bequest of Mrs. Carl L. Selden

CATALOGUE DESCRIPTION

Raised relief in limestone. Upper half of a figure of a nobleman facing right. The figure wears a plain wig and broad-collar necklace. His far hand is raised to his chest and holds a floral scepter (partially preserved). His near arm is extended forwards and downwards, and his missing near hand held an object (staff?) of which is preserved below the far forearm.

Condition: Far elbow missing. Large chips in near forearm and before and behind head. Numerous long cracks, and much of the surface blackened by smoke. Object is set in plaster frame.

EXHIBITIONS

MUSEUM LOCATION

This item is on view on the 19th Dynasty to Roman Period, Martha A. and Robert S. Rubin Gallery, 3rd Floor

CAPTION

Egyptian. Raised Relief of Montuemhat(?), ca. 670–650 B.C.E. Limestone, 14 15/16 x 12 in. (38 x 30.5 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Bequest of Mrs. Carl L. Selden, 1996.146.3. Creative Commons-BY (Photo: Brooklyn Museum, 1996.146.3_SL1.jpg)

IMAGE

overall, 1996.146.3_SL1.jpg. Brooklyn Museum photograph

"CUR" at the beginning of an image file name means that the image was created by a curatorial staff member. These study images may be digital point-and-shoot photographs, when we don\'t yet have high-quality studio photography, or they may be scans of older negatives, slides, or photographic prints, providing historical documentation of the object.

RIGHTS STATEMENT

Creative Commons-BY

You may download and use Brooklyn Museum images of this three-dimensional work in accordance with a Creative Commons license. Fair use, as understood under the United States Copyright Act, may also apply.

Please include caption information from this page and credit the Brooklyn Museum. If you need a high resolution file, please fill out our online application form (charges apply).

For further information about copyright, we recommend resources at the United States Library of Congress, Cornell University, Copyright and Cultural Institutions: Guidelines for U.S. Libraries, Archives, and Museums, and Copyright Watch.

For more information about the Museum's rights project, including how rights types are assigned, please see our blog posts on copyright.

If you have any information regarding this work and rights to it, please contact copyright@brooklynmuseum.org.

RECORD COMPLETENESS

Not every record you will find here is complete. More information is available for some works than for others, and some entries have been updated more recently. Records are frequently reviewed and revised, and we welcome any additional information you might have.