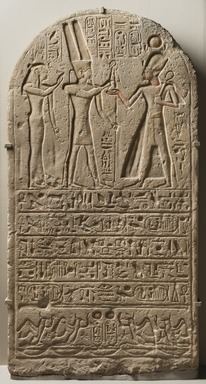

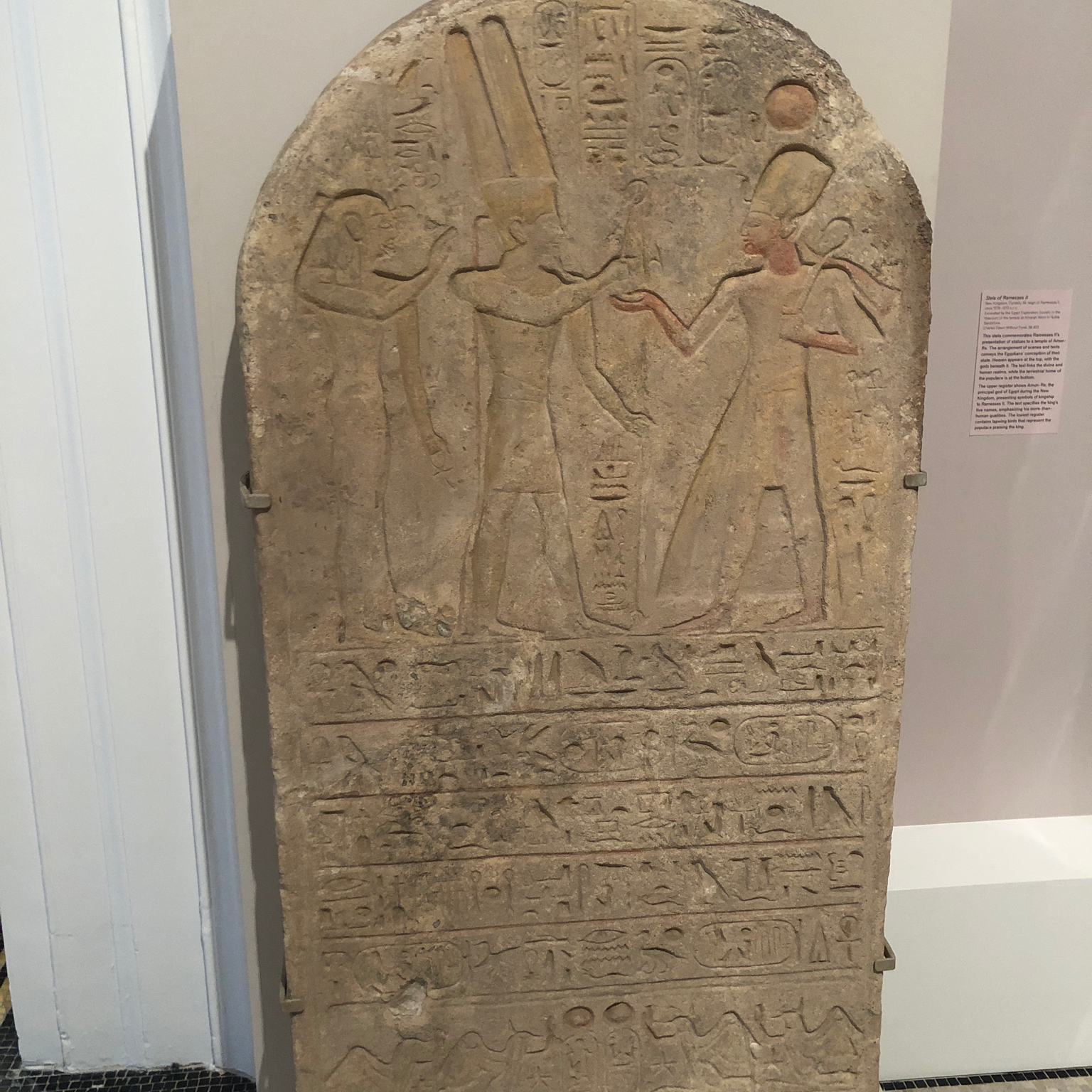

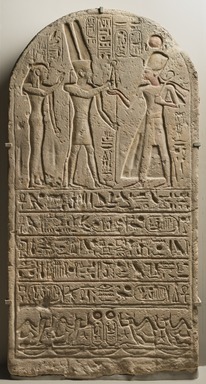

Stela of Ramesses II

Egyptian, Classical, Ancient Near Eastern Art

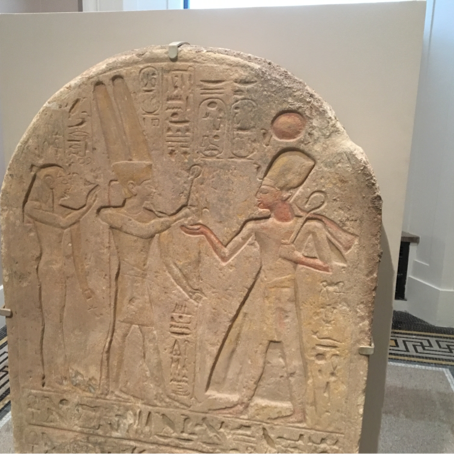

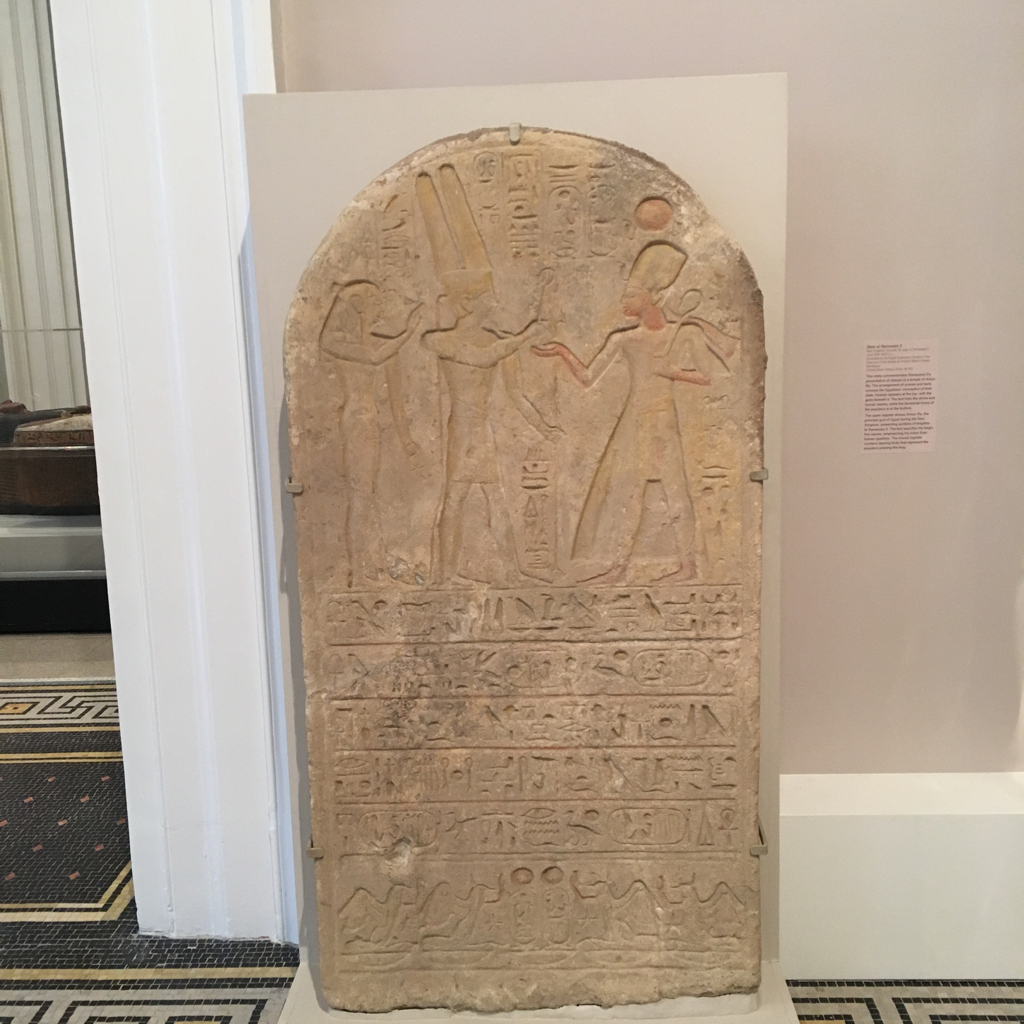

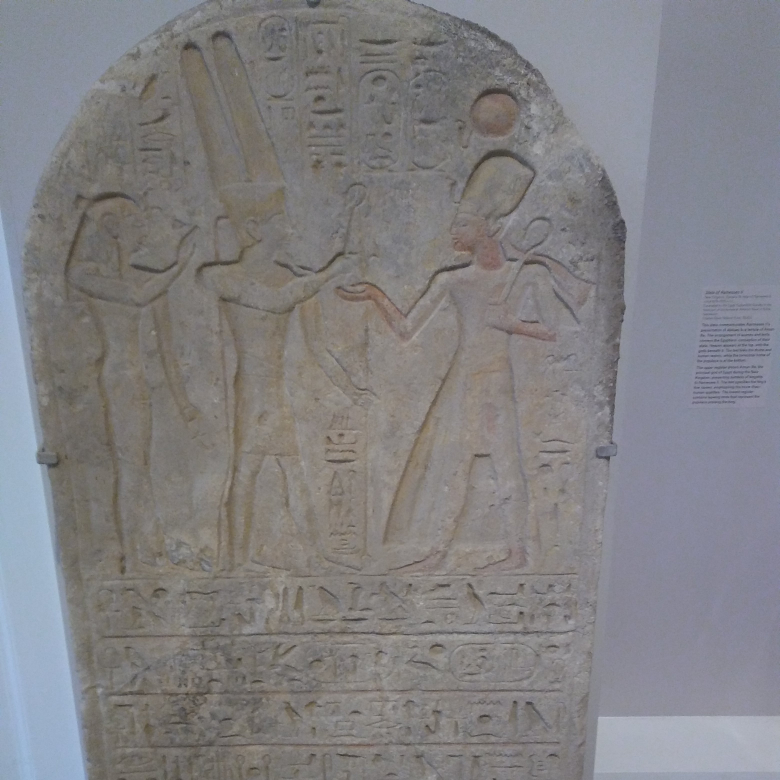

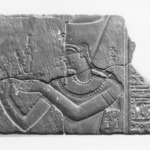

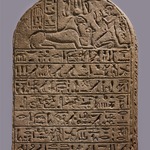

This stela commemorates Ramesses II’s presentation of statues to a temple of Amun-Re. The arrangement of scenes and texts conveys the Egyptians’ conception of their state. Heaven appears at the top, with the gods beneath it. The text links the divine and human realms, while the terrestrial home of the populace is at the bottom.

The upper register shows Amun-Re, the principal god of Egypt during the New Kingdom, presenting symbols of kingship to Ramesses II. The text specifies the king’s five names, emphasizing his more-than-human qualities. The lowest register contains lapwing birds that represent the populace praising the king.

The upper register shows Amun-Re, the principal god of Egypt during the New Kingdom, presenting symbols of kingship to Ramesses II. The text specifies the king’s five names, emphasizing his more-than-human qualities. The lowest register contains lapwing birds that represent the populace praising the king.

MEDIUM

Sandstone

DATES

ca. 1279–1213 B.C.E.

DYNASTY

Dynasty 19

PERIOD

New Kingdom

DIMENSIONS

66 5/16 x 34 5/16 x 7 5/16 in. (168.5 x 87.2 x 18.5 cm) (show scale)

COLLECTIONS

Egyptian, Classical, Ancient Near Eastern Art

ACCESSION NUMBER

39.423

CREDIT LINE

Charles Edwin Wilbour Fund

CATALOGUE DESCRIPTION

Large sandstone stela of Ramesses II, in sunk relief. Upper part shows Ramesses II standing on the right receiving the insignia of kingship from Amun, behind him stands Mut, five rows of hieroglyphs below.

The figures are executed in good XIXth dynasty style and the stela is a good example of conventional work of the period.

Above the figures are six columns of hieroglyphs, and there is one column between the king and Amun.

According to Fairman, "The text gives the titulary of the king and contains a reference to what may be the official name of the town - 'the house of Ramesses - Meriamen'. The ordinary name of the town not recorded on this stela may have been Khenemwaset, 'she-who-unites-with-Thebes'.

At the base of the stela are two cartouches surmounted with disks and flanked on each side with a pair of Rhkyet birds.

Condition: When excavated, the stela was found face down, broken into four parts, but complete. Surface slightly weathered, but in general condition excellent. Faint traces of paint on the bodies and details of upper portion. At the lower left corner is a small depression, but probably ancient.

EXHIBITIONS

MUSEUM LOCATION

This item is not on view

CAPTION

Nubian. Stela of Ramesses II, ca. 1279–1213 B.C.E. Sandstone, 66 5/16 x 34 5/16 x 7 5/16 in. (168.5 x 87.2 x 18.5 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Charles Edwin Wilbour Fund, 39.423. Creative Commons-BY (Photo: Brooklyn Museum, 39.423_overall01_PS22.jpg)

IMAGE

overall, 39.423_overall01_PS22.jpg. Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2024

"CUR" at the beginning of an image file name means that the image was created by a curatorial staff member. These study images may be digital point-and-shoot photographs, when we don\'t yet have high-quality studio photography, or they may be scans of older negatives, slides, or photographic prints, providing historical documentation of the object.

RIGHTS STATEMENT

Creative Commons-BY

You may download and use Brooklyn Museum images of this three-dimensional work in accordance with a Creative Commons license. Fair use, as understood under the United States Copyright Act, may also apply.

Please include caption information from this page and credit the Brooklyn Museum. If you need a high resolution file, please fill out our online application form (charges apply).

For further information about copyright, we recommend resources at the United States Library of Congress, Cornell University, Copyright and Cultural Institutions: Guidelines for U.S. Libraries, Archives, and Museums, and Copyright Watch.

For more information about the Museum's rights project, including how rights types are assigned, please see our blog posts on copyright.

If you have any information regarding this work and rights to it, please contact copyright@brooklynmuseum.org.

RECORD COMPLETENESS

Not every record you will find here is complete. More information is available for some works than for others, and some entries have been updated more recently. Records are frequently reviewed and revised, and we welcome any additional information you might have.