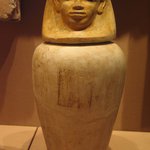

Statuette of Striding Man, ca. 1938–1759 B.C.E. Copper, 4 5/16 x 1 1/4 in. (11 x 3.2 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Charles Edwin Wilbour Fund, 34.1181. Creative Commons-BY (Photo: Brooklyn Museum, CUR.34.1181_erg456.jpg)

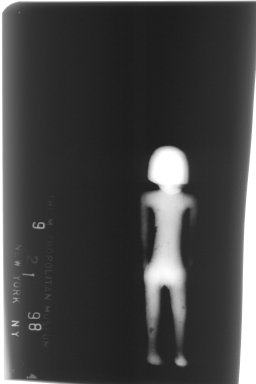

Statuette of Striding Man, ca. 1938–1759 B.C.E. Copper, 4 5/16 x 1 1/4 in. (11 x 3.2 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Charles Edwin Wilbour Fund, 34.1181. Creative Commons-BY (Photo: Brooklyn Museum, CONS.34.1181_1998_xrs_view01.jpg)

Statuette of Striding Man, ca. 1938–1759 B.C.E. Copper, 4 5/16 x 1 1/4 in. (11 x 3.2 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Charles Edwin Wilbour Fund, 34.1181. Creative Commons-BY (Photo: Brooklyn Museum, CUR.34.1181_NegA_print_bw.jpg)

Statuette of Striding Man

Egyptian, Classical, Ancient Near Eastern Art

On View: Egyptian Orientation Gallery, 3rd Floor

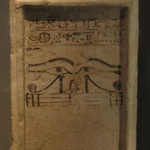

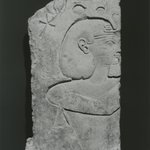

Egyptian artisans used both local and imported metals to make jewelry, vessels, tools, and other objects like the ones displayed here.

Gold existed as a pure metal in the desert east of Luxor and farther south in Nubia, whose name means “Gold Land,” but silver had to be imported from Crete, Cyprus, and Mesopotamia. Most electrum (a natural alloy of gold and silver) was brought from Nubia, but some was made in Egypt. Copper was the most commonly used metal in ancient Egypt.

Beginning in the late Middle Kingdom or shortly thereafter, workers learned how to produce bronze, an alloy of copper and tin, from metalsmiths in western Asia. By the New Kingdom, metalworkers had mastered techniques that are still practiced today, including hammering, soldering, burnishing, engraving, repoussé (creating a raised image on a metal sheet), sheetworking, and casting. In sheetworking—used to make bowls, basins, and some thin jewelry— rough metal slabs called ingots were hammered into thin sheets and shaped into the desired form. Individual sheets could be joined with rivets or by soldering. Workers made tools, statues, and thick jewelry such as rings by pouring molten metal into molds. While many Middle Kingdom objects were solid cast, by the end of the period artisans had learned the lost-wax method of casting, producing hollow metal pieces around a clay core.