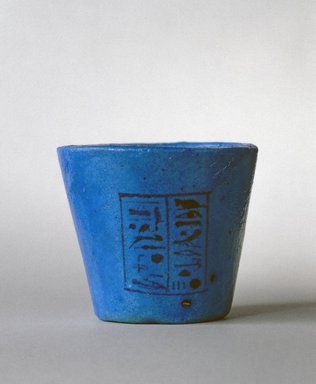

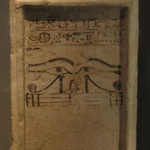

Cup

Egyptian, Classical, Ancient Near Eastern Art

On View: 19th Dynasty to Roman Period, Martha A. and Robert S. Rubin Gallery, 3rd Floor

This cup comes from the burial of a woman named Nesikhonsu. She was the daughter of one high priest of the god Amun-Re, the Wife of another, and herself an important priestess of that deity.

MEDIUM

Faience

DATES

ca. 985–974 B.C.E.

DYNASTY

second half of Dynasty 21

PERIOD

Third Intermediate Period

DIMENSIONS

2 5/16 x Diam. 2 11/16 in. (5.9 x 6.9 cm)

(show scale)

ACCESSION NUMBER

16.73

CREDIT LINE

Gift of Evangeline Wilbour Blashfield, Theodora Wilbour, and Victor Wilbour honoring the wishes of their mother, Charlotte Beebe Wilbour, as a memorial to their father, Charles Edwin Wilbour

CATALOGUE DESCRIPTION

Small faience cup with brilliant blue glaze. Hieroglyph inscription in dark blue, probably manganese, contained in a two column oblong. The inscription proclaims it to the property of Nesi-Khonsu. The entire inscription reads, "Osiris, Foremost of the Great Ones of the Musical Troupe of Amun-Re, Nesi-Khonsu”.

Condition: There are ancient defects in firing, otherwise perfect.

CAPTION

Cup, ca. 985–974 B.C.E. Faience, 2 5/16 x Diam. 2 11/16 in. (5.9 x 6.9 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Evangeline Wilbour Blashfield, Theodora Wilbour, and Victor Wilbour honoring the wishes of their mother, Charlotte Beebe Wilbour, as a memorial to their father, Charles Edwin Wilbour, 16.73. Creative Commons-BY (Photo: Brooklyn Museum, 16.73_SL1.jpg)

IMAGE

overall, 16.73_SL1.jpg. Brooklyn Museum photograph

"CUR" at the beginning of an image file name means that the image was created by a curatorial staff member. These study images may be digital point-and-shoot photographs, when we don\'t yet have high-quality studio photography, or they may be scans of older negatives, slides, or photographic prints, providing historical documentation of the object.

RIGHTS STATEMENT

Creative Commons-BY

You may download and use Brooklyn Museum images of this three-dimensional work in accordance with a

Creative Commons license. Fair use, as understood under the United States Copyright Act, may also apply.

Please include caption information from this page and credit the Brooklyn Museum. If you need a high resolution file, please fill out our online

application form (charges apply).

For further information about copyright, we recommend resources at the

United States Library of Congress,

Cornell University,

Copyright and Cultural Institutions: Guidelines for U.S. Libraries, Archives, and Museums, and

Copyright Watch.

For more information about the Museum's rights project, including how rights types are assigned, please see our

blog posts on copyright.

If you have any information regarding this work and rights to it, please contact

copyright@brooklynmuseum.org.

RECORD COMPLETENESS

Not every record you will find here is complete. More information is available for some works than for others, and some entries have been updated more recently. Records are frequently reviewed and revised, and

we welcome any additional information you might have.

Wow. How did the vase get this rich blue color?

That is made of a really interesting material called faience, considered by Egyptologists as the first high-tech ceramic. The material is made of pure ground quartz, which has a dazzling, white look to it, which is why the ancient Egyptians called it tjehenet (dazzling). The quartz would have several other ingredients added to it; a small part of lime or calcium oxide and soda, all found in the rich desert sands and quarries in their landscape. These ingredients were either added to it before firing in the kiln, so that the beautiful blue would rise to the surface, or it would be put in a vessel of this powder so it would be coated from the outside while fired. Faience is glazed in many different shades of green and blue, which you'll see throughout the galleries.

Do you know anything about the ancient Egyptians using colors for health?

Certain colors were associated with certain meanings, though not directly with health in a medicinal way. Light blue and turquoise, for instance, were seen as interchangeable with green. This meant these colors were linked to the color of water, plants, and vegetation, and were associated with life.

So light blue and green were connected to health, rather than serving as a means to health.