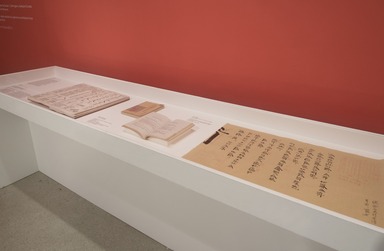

One: Xu Bing, Friday, October 25, 2019 through Sunday, November 29, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_One_Xu_Bing_01_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

One: Xu Bing, Friday, October 25, 2019 through Sunday, November 29, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_One_Xu_Bing_02_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

One: Xu Bing, Friday, October 25, 2019 through Sunday, November 29, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_One_Xu_Bing_03_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

One: Xu Bing, Friday, October 25, 2019 through Sunday, November 29, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_One_Xu_Bing_04_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

One: Xu Bing, Friday, October 25, 2019 through Sunday, November 29, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_One_Xu_Bing_05_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

One: Xu Bing

-

One: Xu Bing

The painting Square Word Calligraphy: Crossing Brooklyn Ferry, Walt Whitman was created specifically for the Brooklyn Museum by Xu Bing, one of China’s most important living artists. This gift celebrates his close relationship with the borough of Brooklyn, where he lived for eighteen years and still has a studio.

The painting also pays homage to the American poet Walt Whitman, who served as an early librarian at the Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library Association (the predecessor of the Brooklyn Museum). Whitman’s now-iconic poem “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry” is part of his collection Leaves of Grass and celebrates the idea that all people are united in our shared human experience. The year 2019 marks the two-hundredth anniversary of Whitman’s birthday, and this exhibition includes material from the Brooklyn Museum Archives and Libraries to highlight the poet’s relationship to the Museum.

Xu Bing first came to the United States in the early 1990s, when language and communication were challenges in his daily life. He discusses the frustrations of that time:

Your thinking ability is mature, but you have the speaking and expressive abilities of a child. You are a respected artist, but in that linguistic context, it’s as if you’re illiterate. Understanding the inner core of a different language helps you understand a different culture. This difference led me to fantasize about being able to “wed” them.

The genesis of the Square Word Calligraphy concept was definitely related to my living environment and conditions. Living in a foreign country means living in a region between two cultures.

In 1993, Xu began developing Square Word Calligraphy, a unique conceptual language organized in square blocks that are shaped like Chinese characters but composed of English letters. He sought to create a system that would demystify calligraphy by combining Chinese calligraphy and English lettering. He has said:

Through this kind of English calligraphy, I gave the West a calligraphic culture with an Eastern form. This text is suspended between two concepts. It belongs, and yet doesn’t belong, to both sides. When people write it, they really don’t know whether they’re writing Chinese or English.

If I had continued living in China, this work would definitely never have appeared, because the cultural conflict wouldn’t have been so direct. And it wouldn’t have become such a vital problem for me. It was a result of my living in New York. But I never would have known about Walt Whitman if I hadn’t lived in Brooklyn.

One: Xu Bing is curated by Susan L. Beningson, Assistant Curator of Asian Art, Brooklyn Museum.

One Brooklyn is made possible by a generous contribution from JP Morgan Chase & Co. -

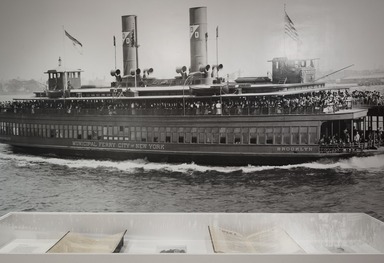

Riding the Brooklyn Ferry

The inauguration of regularly scheduled steam-powered ferry service on May 10, 1814, revolutionized travel between Manhattan and Brooklyn, with the trip taking between five and twelve minutes. The maiden voyage carried 549 passengers, one wagon, and three horses. One of America’s first commuter transportation services, the ferry enhanced access to Lower Manhattan, which was becoming the nation’s business center. The original ferry landing is now part of Brooklyn Bridge Park. Prior to the Brooklyn Bridge’s opening in 1883, the ferry operated eighteen boats carrying 43 million passengers and 1.6 million vehicles annually. After the Bridge opened, the ferry’s importance declined.

The commute of a typical Brooklynite was captured by Walt Whitman in his poem “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry.” In January 1882 he wrote about crossing the East River on the Brooklyn (Fulton) Ferry:

Living in Brooklyn . . . from this time [1840] forward, my life, then and still more the following years, was curiously identified with Fulton ferry, already becoming the greatest of its sort in the world for general importance, volume, variety, rapidity, and picturesqueness. Almost daily, later [1850–60], I cross’d on the boats, often up in the pilothouses where I could get a full sweep, absorbing shows, accompaniments, surroundings. What oceanic currents, eddies, underneath—the great tides of humanity also, with ever-shifting movements. Indeed, I have always had a passion for ferries; to me they afford inimitable, streaming, never-failing, living poems. -

The Chinese American Community in Brooklyn

Brooklyn is home to a large, vibrant, and diverse Asian American community, with Chinese Americans forming the largest portion of this population. Much of Brooklyn’s Asian population is concentrated in three southern Brooklyn neighborhoods: Sunset Park, Bensonhurst, and Avenue U in Sheepshead Bay. The only larger Chinese community within the New York City boroughs is in Queens. An active and economically diverse presence, including professionals, artists, business owners, and laborers, many are recent immigrants. Historically, Chinese immigration to the United States was severely restricted by the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which was repealed in stages beginning in the 1940s. During the exclusion period, a small Chinese community did exist in Brooklyn and elsewhere in New York City, frequently subject to economic and social discrimination. Today, Chinese immigrants compose the second largest group of foreign-born in Brooklyn. Of Brooklyn’s population age 5 and older, almost 46 percent speak a mother language other than English. Census figures show that from 2000 to 2013, the foreign-born Chinese population in New York City jumped 35 percent. During the same period, the foreign-born Chinese population in Brooklyn increased 49 percent. -

Xu Bing

Xu Bing was born in Chongqing, in Sichuan province, in 1955. He spent his childhood years growing up in Beijing; his parents moved there, to work at Beijing University, when he was two years old. His father, to whom the Brooklyn Museum painting is dedicated, was the head of the university’s history department, and his mother worked as a researcher in the department of library science. Xu Bing’s parents instilled in him a love of books and traditional calligraphy. He attributes his fascination with the written word and the physicality and aesthetics of language and books to his parents’ influence. He has written, “To manipulate the written word is to transform the very essence of culture.” Xu studied in the printmaking department at the Central Academy of Fine Arts (CAFA) in Beijing, earning his B.A. in 1981 and M.F.A. in 1987 and later serving as the vice president of CAFA. Among his many awards and honors, in 1999 he was awarded a MacArthur Fellowship (“Genius Grant),” and in 2010 he received the degree Honorary Doctor of Human Letters from Columbia University. -

Walt Whitman

The year 2019 is the two-hundredth anniversary of the birth of the poet Walt Whitman, called the “Bard of Democracy” and considered one of America’s most influential poets. Whitman was born on Long Island and spent his formative years in Brooklyn, attending public schools, and later moved to Camden, New Jersey. He worked as a printer and then a teacher until 1841, when he became a full-time journalist, founding a weekly newspaper, The Long-Islander, and later editing a number of Brooklyn newspapers, including the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. While working for the Eagle, he often visited the Brooklyn Museum and reviewed exhibitions for the newspaper. In 1855 Whitman self-published his collection entitled Leaves of Grass, which was controversial at the time but is now considered a landmark in American literature. The following year he published a revised edition of Leaves of Grass that included a new poem entitled “Sun-Down Poem,” later renamed “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry.” He would continue editing and revising this collection of poetry throughout his life.

-

August 21, 2019

The exhibition features Xu Bing’s Square Word Calligraphy: Crossing Brooklyn Ferry, Walt Whitman, honoring the famous American poet Walt Whitman on his 200th birthday

One: Xu Bing features a new acquisition, Square Word Calligraphy: Crossing Brooklyn Ferry, Walt Whitman (2018), and celebrates the famous American poet’s ties to the Brooklyn Museum during the 200th anniversary of his birth. Xu Bing, widely regarded as one of China’s most important living artists, created this work specifically for the Brooklyn Museum using “square word calligraphy,” a conceptual method of writing English words stylized as Chinese characters that Xu developed while living in Brooklyn in the early 1990s. The resulting painting is a commentary on the immigrant experience of living between two cultures, simultaneously serving as an example of the new traditions and unique perspectives that evolve when cultural experiences are shared. The exhibition, part of the One Brooklyn series focusing on an individual work from the Museum’s collection, is curated by Susan L. Beningson, Assistant Curator, Asian Art, Brooklyn Museum.

Xu Bing was born in China in 1955 and immigrated to the United States in the early 1990s. During his time in the U.S., Xu lived in Brooklyn, where he still maintains a studio today. It was only after arriving in New York that the artist developed his “square word calligraphy” system of writing. Although the form of each rectangular unit resembles a Chinese character, the elements are actually English letters. This unique method of writing is a direct result of his living in the U.S. as an immigrant, straddling two cultures and forming roots in a new “home.”

Square Word Calligraphy: Crossing Brooklyn Ferry, Walt Whitman is a prominent new gift to the Museum’s collection of Chinese art. The large-scale painting features Whitman’s poem Crossing Brooklyn Ferry, which details the narrator’s journey across the East River on a Brooklyn-bound ferry and the excitement he witnessed among his fellow ferry passengers as they came from Manhattan to Brooklyn. Published as part of his famous collection Leaves of Grass, the Whitman poem uses the shared experience of diverse travelers on a crowded ferry to comment on human relationships across time and place. Similarly, Xu Bing’s homage to the poet celebrates the global interconnectedness experienced by immigrants of different ethnic backgrounds melding cultures and creating new traditions.

Whitman, who was known as the American poet of democracy, also served as an early librarian at the Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library Association, the predecessor to the Brooklyn Museum. On view alongside Square Word Calligraphy: Crossing Brooklyn Ferry, Walt Whitman will be material from the Brooklyn Museum Archives celebrating the poet’s relationship to the Museum and the borough. Also included in the exhibition is archival material from Xu Bing illuminating his artistic process in the creation of both “square word calligraphy” and this specific painting. One: Xu Bing will open in conjunction with the newly reinstalled Arts of China and Arts of Japan galleries, highlighting the Museum’s important and diverse collection of works from both countries. Square Word Calligraphy: Crossing Brooklyn Ferry, Walt Whitman was created to honor the reopening of the China collection.

One Brooklyn is made possible by a generous contribution from JP Morgan Chase & Co.

One: Xu Bing

View Original