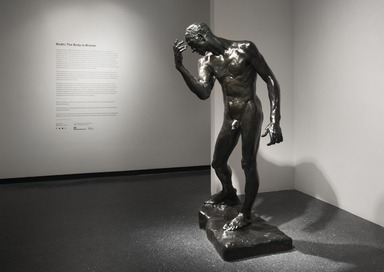

Rodin at the Brooklyn Museum: The Body in Bronze, Friday, November 17, 2017 through Sunday, April 22, 2018 (Image: DIG_E_2017_Rodin_01_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2017)

Rodin at the Brooklyn Museum: The Body in Bronze, Friday, November 17, 2017 through Sunday, April 22, 2018 (Image: DIG_E_2017_Rodin_02_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2017)

Rodin at the Brooklyn Museum: The Body in Bronze, Friday, November 17, 2017 through Sunday, April 22, 2018 (Image: DIG_E_2017_Rodin_03_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2017)

Rodin at the Brooklyn Museum: The Body in Bronze, Friday, November 17, 2017 through Sunday, April 22, 2018 (Image: DIG_E_2017_Rodin_04_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2017)

Rodin at the Brooklyn Museum: The Body in Bronze, Friday, November 17, 2017 through Sunday, April 22, 2018 (Image: DIG_E_2017_Rodin_05_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2017)

Rodin at the Brooklyn Museum: The Body in Bronze, Friday, November 17, 2017 through Sunday, April 22, 2018 (Image: DIG_E_2017_Rodin_06_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2017)

Rodin at the Brooklyn Museum: The Body in Bronze, Friday, November 17, 2017 through Sunday, April 22, 2018 (Image: DIG_E_2017_Rodin_07_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2017)

Rodin at the Brooklyn Museum: The Body in Bronze, Friday, November 17, 2017 through Sunday, April 22, 2018 (Image: DIG_E_2017_Rodin_08_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2017)

Rodin at the Brooklyn Museum: The Body in Bronze, Friday, November 17, 2017 through Sunday, April 22, 2018 (Image: DIG_E_2017_Rodin_09_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2017)

Rodin at the Brooklyn Museum: The Body in Bronze

-

Rodin: The Body in Bronze

Auguste Rodin (1840–1917) began his career in a challenging era for sculpture. For centuries, the academic tradition trained sculptors to produce edifying but often obscure historical subjects in the polished, impersonal style preferred by church and government patrons. By the nineteenth century, allegiance to this classical formula—which remained the typical path to professional success—had drained much sculpture of vitality and relevance in the eyes of many critics. Rodin studied outside this elite and idealizing fine art system and, even while seeking official recognition and accepting civic commissions, chose to emulate and interpret the art of the past in his own unconventional way. In so doing, he radically reimagined the practice and vocabulary of sculpture in ways that would profoundly influence a new generation of modern artists.

The human body was at the heart of Rodin’s sculptural practice. He rendered its form in clay and plaster sculptures; bronze casts of his modeled works were then made by the highly skilled artisans who worked for him. This exhibition focuses on his sculptures cast in bronze, an ancient medium prized in the nineteenth century for public monuments as well as for commercial works.

In Rodin’s art, the body is not deployed in service of the stale narratives, static forms, or lifeless exhortations to virtue that had come to characterize much public sculpture. Instead, it is expressive, vigorously modeled not only to look like, but to feel like, a body—shaped by the artist to suggest an emotive, subjective quality. His figures’ turbulent surfaces, along with their contorted poses and allusive gestures, can convey emotional, carnal, and psychological experiences in all their felt complexity. These are among the qualities that mark Rodin as the first modern sculptor.

Rodin: The Body in Bronze is organized by Lisa Small, Senior Curator, European Art, Brooklyn Museum.

This exhibition is made possible through the generous support of the Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Foundation.

The works in the exhibition are by Auguste Rodin and from the collection of the Brooklyn Museum, Gift of the Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Foundation, unless otherwise indicated. -

Multiples in Bronze

All but one of the bronze sculptures in this exhibition were cast after Rodin’s death. Just before he died, in 1917, he willed his estate, and the right to continue to cast his work after his death, to the French nation. By law, the Musée Rodin in Paris must approve any posthumous casts.

During Rodin’s lifetime, artists did not number their casts and rarely limited the number of casts that could be made of an individual piece. Nearly forty years after his death, France enacted a law limiting the number to twelve. Another law, passed in 1981, makes these multiples subject to a specific numbering system: Eight of the twelve casts are available to the public to purchase and are numbered 1 through 8; the other four, numbered I through IV, are reserved for cultural institutions. In 1986 a French court ruled that bronze casts produced in a limited edition from models crafted by the artist are “considered the artist’s handiwork” and “the sculptor’s death in no way affects the casts’ character as original works and personal creations.” Such casts are termed “original editions.”

When possible, the exhibition labels include the date Rodin originally modeled the work in clay or plaster, and identify which foundry cast the work in bronze. The labels also include the edition and cast numbers, when known. -

Auguste Rodin

Born in Paris in 1840 to a modest family, Rodin enrolled at age fourteen in the École Impériale Spéciale de Dessin et de Mathématiques, a government school for craft and design. It was better known as the “Petite École,” to distinguish it from the far more prestigious École des Beaux-Arts—the official fine arts school of the French Academy, whose entrance examination Rodin failed three times in a row. At the Petite École, he studied drawing and sculpture, while also spending time studying and drawing at the Louvre, the Botanical Garden, and the Museum of Natural History.

From the late 1850s through the 1870s, Rodin supported himself by working for a variety of decorative and ornamental sculptors, as well as for the Sèvres Porcelain Factory. In 1864 he met his lifelong companion, Rose Beuret, and set up a solo studio in Paris. He first exhibited at the Paris Salon in 1875, and the next year traveled to Italy to study the works of Michelangelo. At the 1877 Salon he showed The Age of Bronze, a sculpture of a male nude that garnered tremendous attention for Rodin, who was falsely accused of having made the plaster cast directly from the body of his model.

The last twenty years of the nineteenth century were a time of great artistic output and recognition for Rodin. In addition to the many portraits he made of friends, family, colleagues, and paying customers, this was the period of his most important public works. In 1880 he moved to a new studio in Paris, and he was awarded the commission for The Gates of Hell, a project he never completed but that remained a creative wellspring for him for the rest of his career. In 1885 and 1891 he received two other significant commissions: The Burghers of Calais and the Monument to Balzac. He worked on a number of other public commissions, some ultimately unrealized, and then in 1900, to coincide with the Exposition Universelle, he organized his first solo exhibition to be held in Paris.

Rodin continued to travel and exhibit around the world in the early years of the twentieth century, receiving many official honors. In 1895 he purchased a villa in the Paris suburb of Meudon, where he lived and had additional studio space. In 1902 he met the Bohemian-Austrian poet Rainer Maria Rilke, who served as the artist’s personal secretary for eight months in 1905 and published an influential monograph about him. In 1908 he moved into an eighteenth-century mansion called the Hôtel Biron, in Paris, which he used as a showroom rather than a studio.

In 1916 Rodin suffered a stroke, and by the end of that year the seriously ill artist offered to donate all his works to the French nation if it agreed to convert the Hôtel Biron into a museum in his honor. An agreement was reached eleven months before the artist’s death on November 17, 1917. The Musée Rodin opened in 1919. -

Inspired by Antiquity

In my studio I have fragments of gods for my everyday delight; they are the blessing upon my spiritual life, and every day I stand in ardent admiration before their joyous divine sensuality.

—Auguste Rodin (1904)

The same completeness is conveyed in all the armless statues of Rodin; nothing necessary is lacking. One stands before them as before something whole.

—Rainer Maria Rilke (1903)

Rodin created numerous fragments and partial figures, and considered them to be independent works of art, a strategy that challenged prevailing sculptural standards and was often received with incomprehension and insult.

In 1893 the artist began to collect Egyptian, Greek, and Roman antiquities, eventually accumulating more than six thousand marble and bronze fragments, as well as vessels and other figurines in terracotta or stone, all of which are now in the collection of the Musée Rodin. He particularly esteemed the lifelike modeling of the ancient Greek sculptors whose works he drew at the Louvre, believing them to be “the most admirable observers of Nature that ever lived.” He saw a precedent for his own exploration of the evocative human figure in their works, as well as in those of Michelangelo— the artist, Rodin claimed, who “revealed me to myself, revealed to me the truth of forms.”

Rodin found symbolic and aesthetic inspiration in ancient sculptures that were missing arms or heads. Like the Romantic generation before him, he saw such works as rich metaphors for a vanished past and the ravages of time. He also appreciated them as self-sufficient forms that did not require any narrative context to be powerfully expressive. When Rodin exhibited his own partial figures, often roughly modeled and retaining the marks and accidents inherent to the sculpting and casting process, they were criticized as “unfinished.” But Rodin deemed them complete, believing that a part could convey the emotive essence of a larger whole. He also believed that partial figures and roughly modeled surfaces that seemed to pulse with inner movement added a temporal dimension to a sculpture, allowing it to “become part of life, to which there is no beginning nor end, but only perpetual development.” This radical reassessment of the meaning and form of sculpture is fundamental to Rodin’s widely recognized legacy as the first modern sculptor.

The antique fragments on view in this gallery, drawn from the Brooklyn Museum’s permanent collection, are similar to those Rodin collected. -

Heads and Portraits

There is no artistic work that requires as much penetrating insight as the bust and the portrait. People sometimes believe that the profession of the artist demands more manual skill than intelligence. It suffices to look at a good bust to redress this error. Such a work is the equivalent of a biography.

—Auguste Rodin (1911)

Rodin created many heads and portrait busts throughout his career. Whether capturing family, friends, artists, or public figures, he studied his subjects and their expressions from all angles and profiles, took multiple skull measurements, made sketches, and typically requested as many as twelve sittings. In the case of Honoré de Balzac, who was dead when Rodin received the commission for his portrait, the artist consulted photographs and observed living models who he thought resembled his subject.

He worked after live models even for heads destined to be decorative or allegorical, or for historical figures whose faces were unknown, as in The Burghers of Calais.

For Rodin, this was the only way he felt he could invest them with the same sense of emotional life and vitality he conferred on his individual portraits: “I can only work with a model. . . . I declare that I have no ideas when I have nothing to copy; but when nature shows me her forms, right away I find something worth saying and even developing.”

Although he excelled at capturing likenesses, Rodin was perhaps more concerned with rendering the essential, internal energy of his sitters. This was particularly true of his portraits of fellow artists: famed author Victor Hugo’s furrowed brow and composer Gustav Mahler’s hair haloing his high forehead give physical form to their intellectual and creative vigor. His incisive portrayals of Hugo and of the handyman who posed for Man with the Broken Nose show the influence of ancient Roman portrait busts, which Rodin considered exemplars of naturalism. -

Thank You, Iris and B. Gerald Cantor

Nearly all of the works in this exhibition were generously given to the Brooklyn Museum by the Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Foundation. Collectors and philanthropists, the Cantors made it their mission to preserve and disseminate the legacy and work of Auguste Rodin. Their Foundation, established in 1978, supports this goal, as well as providing substantial funding for a variety of medical, educational, and cultural institutions and projects.

B. Gerald Cantor purchased his first Rodin sculpture in 1946. By the time of his death in 1996, he had acquired more than seven hundred works by Rodin and had donated hundreds of them to museums across the United States. Iris Cantor, his widow and now president of the Foundation, is a Brooklyn native who, as her husband once noted, experienced “her first joys of aesthetic discovery” here at the Brooklyn Museum.

We are deeply grateful to the Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Foundation not only for the Rodin sculptures we are privileged to share with our audiences, but also for their significant support of our institution and its programming through the years. -

Monument to Balzac

I am happy to announce to you officially that the Committee of the Société des Gens de Lettres . . . selected you . . . to execute the statue of Balzac, which is to be erected on the Square of the Palais Royal. . . .We all expect from your great talent a superb work.

—Émile Zola to Rodin (1891)

“Balzac” . . . remains the incontestable point of departure for modern sculpture.

—Constantin Brancusi (1952)

As soon as Rodin received the commission to portray the French realist author Honoré de Balzac (1799–1850), he immersed himself in extensive research on his subject’s appearance. Since he could not study Balzac in person, he consulted photographs and portraits, read descriptions of the writer, and visited his birthplace in Tours, France, to sketch its inhabitants. He even ordered a robe and trousers from Balzac’s tailor in the author’s size.

Rodin made more than fifty studies of Balzac during the seven years he devoted to the project, including portrait heads and clothed and nude figures. As the work evolved, he began to move away from a realistic vision of the portly author and toward a more conceptual evocation of his creative genius: “For me, Balzac is before everything a creator, and this is the idea I would wish to make understood in my statue.”

Just as his Burghers of Calais introduced a new kind of public memorial sculpture that emphasized the heroism of despair instead of triumph, Rodin’s monument to Balzac was a radical departure from traditional commemorative portraiture. The commission committee had already been uneasy with the preliminary studies, which presented a decidedly unidealized man. Rodin’s final, full-size plaster depicted the author’s large body casually enveloped in an abstracted dressing gown, with only his roughly modeled face and disheveled hair to give any indication of his identity. Rodin conceived of a Balzac in the throes of creation:

. . . in his study, breathless, hair in disorder, eyes lost in a dream . . . Balzac truly heroic who does not stop to rest for a moment, who makes night into day . . . who is transported by passion. . . . It seems to me that such a Balzac . . . seen in a public place would be greater and more worthy of admiration than just any writer who sits in a chair or who proudly poses for the enthusiastic crowd . . . there is nothing more beautiful than the absolute truth of real existence.

Critics did not agree and were merciless in their ridicule and condemnation, comparing the work to “a sack of potatoes” and “a lump of plaster kicked together by a lunatic.” The monument was rejected. The first bronze cast of it was not installed in Paris until 1939. -

The Body in Pieces

Rodin changed how we think about sculpture by insisting that just a part of a figure—such as a torso or a hand—could by itself convey meaning and thus be a complete work of art. A related practice at the heart of Rodin’s creative process was known as marcottage: reusing and reconfiguring existing sculptural forms to generate new figural compositions, a technique that can be seen as a precursor to modern assemblage art.

As a first step in a sculpture to be cast in bronze, Rodin would sculpt the form in clay, typically working from a live model, and then have one or more plaster casts made of the work. He also might sculpt directly in plaster. One of his studio assistants described the centrality of these plasters to Rodin’s working method:

He had several plasters made. One was kept intact, the others were cut apart, and the sections numbered and catalogued, so that they might be drawn out of the cupboards to serve in other figures, perhaps years later. Thus dissected, limb from torso, they would be set, again and again, in new arrangements and further thoughtful groupings. Until at last the work had his full-hearted consent.

This process had its roots in Rodin’s early training in commercial sculpture studios, where he made models of decorative works destined to be mass-produced in series and variations. During the course of his work on The Gates of Hell, his inventory of sculpted body “ready-mades” grew, filling his studio in the Paris suburb of Meudon. By selecting and recombining his own plaster fragments and figures (sometimes in enlarged or reduced form), Rodin explored new juxtapositions and latent meanings, redefining sculpture as always in flux and never finished—a very modern concept. -

In the Workshop

For centuries and through to the present day, creating sculpture has been a collaborative process between the artist and a range of artisans and craftspeople. In the late nineteenth century, both public and domestic sculpture were in high demand, and Rodin maintained a large workshop to ensure that he captured as much of that market as possible. By 1900 he employed as many as fifty people, including models, plaster casters, marble carvers, bronze founders, patinators, and reduction and enlargement technicians, as well as studio assistants and pupils.

Working in his studio from live models, Rodin typically generated concepts for sculptures in clay, as one eyewitness recounted: “We often saw naked women and men who walked around him. He paid them to live and move before his eyes. If he caught one of them in a pose that struck him, he asked the model to stop walking and quickly he fashioned a small sculpture in clay.” Skilled assistants would then make a plaster cast of the sculpted clay figure that captured every bump and depression in its surface. This plaster, or an enlargement or reduction of it produced by another skilled artisan, represented Rodin’s vision for a completed work. Professional founders used the plaster cast as the basis for creating bronze sculptures. A video depicting the process of bronze casting can be seen in this gallery.

Rodin supervised the translation of his clay models into other materials, but like most sculptors of his generation, he was never directly involved in the casting process. Even the signatures on his bronzes were stamped by the foundries, a gesture that demonstrates their central role within his process. -

The Burghers of Calais

After France’s humiliating defeat in the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71), the government took a renewed interest in public monuments to valor that would have patriotic appeal. In 1884 the city of Calais commissioned Rodin to create a monument commemorating the heroism of six men from that French port in the fourteenth century, during the Hundred Years’ War. According to a contemporaneous account, in 1347 the English king Edward III agreed to lift his yearlong siege of Calais and spare its inhabitants further suffering if six burghers (wealthy and prominent citizens) offered themselves to him in exchange. They left their city—barefoot, bareheaded, with ropes around their necks, conflicted but steadfast—and surrendered to the king, fully aware that he meant to execute them. Moved by their bravery and fearing their death would bring bad luck to her unborn child, the English queen Philippa persuaded her husband not to kill the burghers. The six men, and the city for which they would have sacrificed their lives, were saved.

The Burghers of Calais exemplifies Rodin’s ability to convey psychological states through the gesture, posture, and agitated surface of the body. A head bent under the weight of clasped hands; shoulders collapsed in submission; toes that flex or rest tentatively on the ground; tensed muscles and hanging arms; firm lips and open mouths; furrowed brows and hollowed eyes: These corporeal signs forcefully communicate the complex mixture of anguish, ambivalence, and resignation that defines a single moment and captures a timeless, universal humanity.

The depiction of the burghers as vulnerable individuals in a moment of internal turmoil was criticized by the Calais city council, which expected a more conventionally heroic presentation. Rodin was determined to pursue his concept of the famous episode, which established the terms of a modern, anti-monumental tradition of civic sculpture. As he stated:

I have not shown them grouped in a triumphant apotheosis; such a glorification of their heroism would not have corresponded to anything real. On the contrary, I have . . . strung them one behind the other, because in the indecision of the final inner combat which arises between their devotion to their city and their fear of dying, each of them is isolated in front of his conscience. They are still questioning themselves to know if they have the strength to accomplish the supreme sacrifice. . . .Their soul pushes them onward, and yet their feet refuse to walk.

The Brooklyn Museum collection includes bronze casts of three of the six large figures that comprise the final Burghers of Calais monument, as well as a large burgher in the nude (on display at the entrance of this exhibition) and the related maquette, fragments, and reductions on view nearby. -

The Gates of Hell

He has endowed hundreds and hundreds of figures that were only a little larger than his hand with the life of all passions, the blossoming of all delights and the burden of all vices. He has created bodies that touch each other all over and cling together like animals bitten into each other . . . chains of bodies, garlands and tendrils and heavy clusters of bodies . . .

—Rainer Maria Rilke (1903)

This churning mass of bodies described by the poet (and, briefly, Rodin’s personal secretary) Rainer Maria Rilke was part of the most ambitious and prolific project of the artist’s career: a large portal adorned with relief sculptures that was to grace the entrance of a proposed museum of decorative arts in Paris. It was commissioned in 1880 by the state, and for its theme Rodin chose Dante’s Divine Comedy, an epic fourteenth-century poem about a journey through Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise. He initially based his design on the format of Lorenzo Ghiberti’s fifteenth-century Gates of Paradise, massive bronze doors decorated with compartments of narrative reliefs, made for the Baptistery in Florence.

For The Gates of Hell, as it became known, Rodin molded hundreds of figures drawn not only from Dante but also from the Bible, classical mythology, and the poetry of Charles Baudelaire. The design evolved, too, from a formal grid of panels to an amorphous field encrusted with solitary and entangled figures, modeled in high relief and in the round, that Rodin would place and replace as his composition developed. Emerging from the molten surface of the doorway—which was more than twenty feet high and thirteen feet across—Rodin’s restless figures embody the desires and conflicts that define the human condition.

The museum was never built, and as a result the commission was canceled, but Rodin continued to work on The Gates of Hell for the rest of his life. It became for him a site of profound artistic inquiry, experimentation, and invention, with many of the plaster figures he modeled for it recycled, enlarged, reduced, fragmented, or recombined and then cast as new, independent sculptures, several examples of which are on view nearby. The Gates of Hell was so consuming that even figures and groups that have never been identified within Rodin’s evolving composition may still be considered part of its lineage.

The Gates of Hell was never cast in bronze during Rodin’s lifetime. According to his wishes, a limited number of bronze casts have been made posthumously.