Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland, 1861–2008, January 31, 2015 through September 11, 2016 (Image: DIG_E_2015_Coney_Island_Visions_01_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2015)

Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland, 1861–2008, January 31, 2015 through September 11, 2016 (Image: DIG_E_2015_Coney_Island_Visions_02_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2015)

Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland, 1861–2008, January 31, 2015 through September 11, 2016 (Image: DIG_E_2015_Coney_Island_Visions_03_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2015)

Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland, 1861–2008, January 31, 2015 through September 11, 2016 (Image: DIG_E_2015_Coney_Island_Visions_04_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2015)

Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland, 1861–2008, January 31, 2015 through September 11, 2016 (Image: DIG_E_2015_Coney_Island_Visions_05_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2015)

Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland, 1861–2008, January 31, 2015 through September 11, 2016 (Image: DIG_E_2015_Coney_Island_Visions_06_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2015)

Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland, 1861–2008, January 31, 2015 through September 11, 2016 (Image: DIG_E_2015_Coney_Island_Visions_07_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2015)

Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland, 1861–2008, January 31, 2015 through September 11, 2016 (Image: DIG_E_2015_Coney_Island_Visions_08_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2015)

Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland, 1861–2008, January 31, 2015 through September 11, 2016 (Image: DIG_E_2015_Coney_Island_Visions_09_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2015)

Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland, 1861–2008, January 31, 2015 through September 11, 2016 (Image: DIG_E_2015_Coney_Island_Visions_10_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2015)

Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland, 1861–2008, January 31, 2015 through September 11, 2016 (Image: DIG_E_2015_Coney_Island_Visions_11_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2015)

Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland, 1861–2008, January 31, 2015 through September 11, 2016 (Image: DIG_E_2015_Coney_Island_Visions_12_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2015)

Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland, 1861–2008, January 31, 2015 through September 11, 2016 (Image: DIG_E_2015_Coney_Island_Visions_13_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2015)

Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland, 1861–2008, January 31, 2015 through September 11, 2016 (Image: DIG_E_2015_Coney_Island_Visions_14_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2015)

Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland, 1861–2008, January 31, 2015 through September 11, 2016 (Image: DIG_E_2015_Coney_Island_Visions_15_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2015)

Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland, 1861–2008, January 31, 2015 through September 11, 2016 (Image: DIG_E_2015_Coney_Island_Visions_16_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2015)

Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland, 1861–2008, January 31, 2015 through September 11, 2016 (Image: DIG_E_2015_Coney_Island_Visions_17_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2015)

Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland, 1861–2008, January 31, 2015 through September 11, 2016 (Image: DIG_E_2015_Coney_Island_Visions_18_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2015)

Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland, 1861–2008, January 31, 2015 through September 11, 2016 (Image: DIG_E_2015_Coney_Island_Visions_19_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2015)

Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland, 1861–2008, January 31, 2015 through September 11, 2016 (Image: DIG_E_2015_Coney_Island_Visions_20_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2015)

Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland, 1861–2008, January 31, 2015 through September 11, 2016 (Image: DIG_E_2015_Coney_Island_Visions_21_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2015)

Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland, 1861–2008, January 31, 2015 through September 11, 2016 (Image: DIG_E_2015_Coney_Island_Visions_22_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2015)

Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland, 1861–2008, January 31, 2015 through September 11, 2016 (Image: DIG_E_2015_Coney_Island_Visions_23_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2015)

Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland, 1861–2008, January 31, 2015 through September 11, 2016 (Image: DIG_E_2015_Coney_Island_Visions_24_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2015)

Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland, 1861–2008, January 31, 2015 through September 11, 2016 (Image: DIG_E_2015_Coney_Island_Visions_25_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2015)

Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland, 1861–2008, January 31, 2015 through September 11, 2016 (Image: DIG_E_2015_Coney_Island_Visions_26_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2015)

Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland, 1861–2008, January 31, 2015 through September 11, 2016 (Image: DIG_E_2015_Coney_Island_Visions_27_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2015)

Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland, 1861–2008, January 31, 2015 through September 11, 2016 (Image: DIG_E_2015_Coney_Island_Visions_28_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2015)

Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland, 1861–2008, January 31, 2015 through September 11, 2016 (Image: DIG_E_2015_Coney_Island_Visions_29_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2015)

Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland, 1861–2008, January 31, 2015 through September 11, 2016 (Image: DIG_E_2015_Coney_Island_Visions_30_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2015)

Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland, 1861–2008, January 31, 2015 through September 11, 2016 (Image: DIG_E_2015_Coney_Island_Visions_31_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2015)

Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland, 1861–2008, January 31, 2015 through September 11, 2016 (Image: DIG_E_2015_Coney_Island_Visions_32_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2015)

Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland, 1861–2008, January 31, 2015 through September 11, 2016 (Image: DIG_E_2015_Coney_Island_Visions_33_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2015)

Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland, 1861–2008, January 31, 2015 through September 11, 2016 (Image: DIG_E_2015_Coney_Island_Visions_34_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2015)

Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland, 1861–2008

-

Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland, 1861–2008

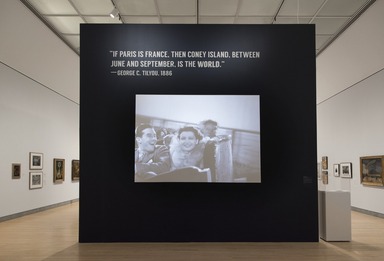

From its inception as an elite seaside resort and evolution into an entertainment mecca for the masses to its decades- long decline and recent revival, Coney Island has inspired a wide range of art, music, literature, and film. Known as America’s Playground, this world-famous amusement center at the southern tip of Brooklyn has become a national cultural symbol.

This exhibition, the first to consider Coney Island’s enduring status as artistic subject, brings together paintings, drawings, photographs, prints, banners, architectural artifacts, and carousel animals—as well as film clips and ephemera—to examine how artists have used this iconic place as a prism through which to view the American experience. Divided into five chronological sections with titles that reflect changing popular perceptions of Coney Island, the exhibition traces the resort’s rise, decline, and struggle to be reborn.

The artistic visions on display—at first imagining the future, and later recalling the past—convey changing ideas about leisure while exploring issues of race, ethnicity, and class. Ultimately, they also reveal how and why this historic destination became part of the collective memory of the American people. -

Down at Coney Isle 1861–1894

The wealthy and adventurous had been vacationing in hotels at Coney Island, one of America’s earliest seaside resorts, since 1829. At first, visitors traversed a road paved with oyster shells and crossed a wooden bridge over Coney Island Creek to get to the site. By the beginning of the Civil War, Coney Island had become a destination for a wide spectrum of tourists from New York, the nation’s most congested and diverse city. From 1861 to 1894, advances in transportation—steamboats, regular ferry service, horse trams, and steam rail links—made it increasingly easier and cheaper to reach the resort.

Artists pictured Coney Island from the Civil War era through the early decades of the Gilded Age as a growing leisure and entertainment locale. Charles Fremont’s nineteenth-century song “Down at Coney Isle” described the city’s sandy backyard as a place to meet people from different neighborhoods in a leisurely setting that promised romance: “There’s the Bow’ry boys with Nellie, and the East Side girls in style. / The girls from up in Harlem, too, and Johnny with his smile.” -

The World's Greatest Playground 1895–1929

At the turn of the twentieth century, extravagant amusement parks—Steeplechase, Luna, and Dreamland—transformed Coney Island into the “World’s Greatest Playground,” the most famous mechanical amusement center in the world. The enclosed parks combined the earlier traditions of the dime museum, circus, fairground, and world’s fair. By imaginatively transporting visitors to foreign countries, throwing strangers together on high-speed rides, and extending leisure time far into the night with its blaze of electricity, Coney Island revolutionized the way people played. An emblem of America’s modernity, the site was a laboratory for the invention and testing of social, commercial, and technological ideas that would later shape the nation as a whole.

Coney Island’s parks were built at the buoyant turn of the twentieth century, when incomes were rising and working hours decreasing for many, albeit not all, Americans. The modern American popular-culture industry was born at Coney Island as aggressive mass-advertising techniques were used to promote entertainment venues. America’s Playground became not just an attraction for the crowds but also a seductively liberating subject for artists, photographers, songwriters, and filmmakers. -

Carousel Animals

Carousels were being carved in England and Germany before they became popular in America. The inventor William F. Mangels, who immigrated to New York from Germany, patented the overhead gears that controlled the galloping motion of the carousel horse in 1907. His design became standard in the field. Mangels collaborated with Coney Island’s best wood-carvers, many of whom were also immigrants.

Between 1880 and 1920, Coney Island produced a distinctive style of carved carousel animals characterized by flamboyant decorations and expressive faces. They were the product of Danish-born Charles I. D. Looff and the wood-carvers he inspired, including Solomon Stein, Harry Goldstein, and Charles Carmel, whose horses are shown here. Stein, Goldstein, and Carmel were Jewish wood-carvers who fled anti-Semitism in Eastern Europe and brought to America a tradition of carving symbolic animal imagery for synagogues. They found an outlet for their talent in the American carousel industry. -

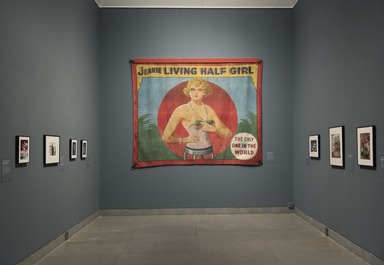

The Nickel Empire 1930–1939

In late October 1929, the stock market crashed, beginning a downward spiral of tightening credit and growing unemployment that plunged the nation into a decade-long depression. As the country’s economic promise waned in the 1930s, Coney Island lost some of its luster. No longer considered the World’s Greatest Playground for the working and middle classes, it instead became known as the Paradise for the Proletariat, the Poor Man’s Riviera, and, most popularly, the Nickel Empire. For five cents, day-trippers could take the subway to Coney Island, where they could enjoy the beach and the longest boardwalk in the world, frequent the rides, watch the bally (sample) performances outside the sideshows, and eat Nathan’s Famous hot dogs, which cost a nickel each.

Over a million visitors a day flocked to Coney Island, among them the poor, those once comfortably middle-class, and, more surprisingly, wealthier customers who learned to relax in democratic style as ostentation went out of fashion. Artists during this turbulent decade captured the vivacity of these crowds, many of whom went to Coney Island as a break from the economic and social realities of life. -

A Coney Island of the Mind 1940–1961

The so-called Beat generation that largely came of age following World War II questioned social conformity as well as literary and artistic traditions. The San Francisco Beat poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s hallucinogenic book A Coney Island of the Mind (1958) took its title from the novelist Henry Miller, who had first used the phrase in Black Spring (1936) and Into the Night Life (1947). These writers adopted Coney Island as a cultural metaphor for beauty, absurdity, and spiritual longing.

Many visual artists saw Coney Island not merely as a place but also as a personal state of mind and a symbol of the collective soul of a nation. Beginning in the 1940s, both magical and maniacal images pictured Coney Island, in Ferlinghetti’s words, as a teetering, tumbling “circus of the soul.” From just before the attack on Pearl Harbor through the early years of the Cold War, artists’ visions of Coney Island mirrored global conflicts abroad along with dramatic changes on the home front. -

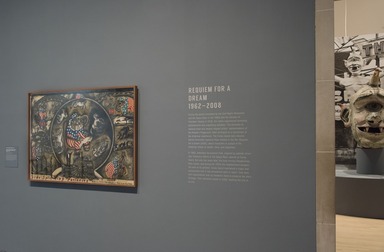

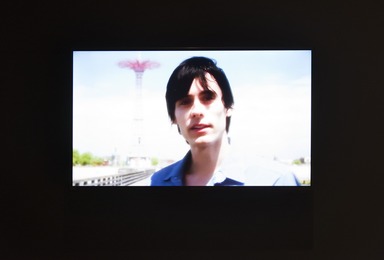

Requiem for a Dream 1962–2008

During the period bracketed by the Civil Rights Movement and the Space Race in the 1960s and the election of President Obama in 2008, the nation experienced promising achievements and anguishing setbacks. The extremes of national hope and despair shaped artists’ representations of the People’s Playground, often portrayed as a microcosm of the American experience. The Coney Island–born director Darren Aronofsky explored these themes in the film Requiem for a Dream (2000), about characters in pursuit of the American dream of wealth, fame, and happiness.

In 1962, Astroland Amusement Park, inspired by patriotic fervor over America’s efforts in the Space Race, opened at Coney Island. But only two years later, the long-running Steeplechase Park closed, and during the 1970s the neighborhood decayed. Yet even at its grittiest, Coney Island maintained a magic that transcended that of any amusement park or resort. Over time, arts organizations took up residence there to preserve the site’s heritage. Then Astroland closed in 2008, marking the end of an era.