Fine Lines: American Drawings from the Brooklyn Museum, Friday, March 08, 2013 through Sunday, January 18, 2015 (Image: DIG_E_2013_Fine_Lines_001_PS4.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2013)

Fine Lines: American Drawings from the Brooklyn Museum, Friday, March 08, 2013 through Sunday, January 18, 2015 (Image: DIG_E_2013_Fine_Lines_002_PS4.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2013)

Fine Lines: American Drawings from the Brooklyn Museum, Friday, March 08, 2013 through Sunday, January 18, 2015 (Image: DIG_E_2013_Fine_Lines_003_PS4.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2013)

Fine Lines: American Drawings from the Brooklyn Museum, Friday, March 08, 2013 through Sunday, January 18, 2015 (Image: DIG_E_2013_Fine_Lines_004_PS4.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2013)

Fine Lines: American Drawings from the Brooklyn Museum, Friday, March 08, 2013 through Sunday, January 18, 2015 (Image: DIG_E_2013_Fine_Lines_005_PS4.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2013)

Fine Lines: American Drawings from the Brooklyn Museum, Friday, March 08, 2013 through Sunday, January 18, 2015 (Image: DIG_E_2013_Fine_Lines_006_PS4.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2013)

Fine Lines: American Drawings from the Brooklyn Museum, Friday, March 08, 2013 through Sunday, January 18, 2015 (Image: DIG_E_2013_Fine_Lines_007_PS4.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2013)

Fine Lines: American Drawings from the Brooklyn Museum, Friday, March 08, 2013 through Sunday, January 18, 2015 (Image: DIG_E_2013_Fine_Lines_008_PS4.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2013)

Fine Lines: American Drawings from the Brooklyn Museum, Friday, March 08, 2013 through Sunday, January 18, 2015 (Image: DIG_E_2013_Fine_Lines_009_PS4.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2013)

Fine Lines: American Drawings from the Brooklyn Museum, Friday, March 08, 2013 through Sunday, January 18, 2015 (Image: DIG_E_2013_Fine_Lines_010_PS4.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2013)

Fine Lines: American Drawings from the Brooklyn Museum, Friday, March 08, 2013 through Sunday, January 18, 2015 (Image: DIG_E_2013_Fine_Lines_011_PS4.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2013)

Fine Lines: American Drawings from the Brooklyn Museum, Friday, March 08, 2013 through Sunday, January 18, 2015 (Image: DIG_E_2013_Fine_Lines_012_PS4.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2013)

Fine Lines: American Drawings from the Brooklyn Museum, Friday, March 08, 2013 through Sunday, January 18, 2015 (Image: DIG_E_2013_Fine_Lines_013_PS4.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2013)

Fine Lines: American Drawings from the Brooklyn Museum, Friday, March 08, 2013 through Sunday, January 18, 2015 (Image: DIG_E_2013_Fine_Lines_014_PS4.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2013)

Fine Lines: American Drawings from the Brooklyn Museum, Friday, March 08, 2013 through Sunday, January 18, 2015 (Image: DIG_E_2013_Fine_Lines_015_PS4.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2013)

Fine Lines: American Drawings from the Brooklyn Museum, Friday, March 08, 2013 through Sunday, January 18, 2015 (Image: DIG_E_2013_Fine_Lines_016_PS4.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2013)

Fine Lines: American Drawings from the Brooklyn Museum, Friday, March 08, 2013 through Sunday, January 18, 2015 (Image: DIG_E_2013_Fine_Lines_017_PS4.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2013)

Fine Lines: American Drawings from the Brooklyn Museum, Friday, March 08, 2013 through Sunday, January 18, 2015 (Image: DIG_E_2013_Fine_Lines_018_PS4.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2013)

Fine Lines: American Drawings from the Brooklyn Museum, Friday, March 08, 2013 through Sunday, January 18, 2015 (Image: DIG_E_2013_Fine_Lines_019_PS4.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2013)

Fine Lines: American Drawings from the Brooklyn Museum, Friday, March 08, 2013 through Sunday, January 18, 2015 (Image: DIG_E_2013_Fine_Lines_020_PS4.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2013)

Fine Lines: American Drawings from the Brooklyn Museum, Friday, March 08, 2013 through Sunday, January 18, 2015 (Image: DIG_E_2013_Fine_Lines_021_PS4.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2013)

Fine Lines: American Drawings from the Brooklyn Museum, Friday, March 08, 2013 through Sunday, January 18, 2015 (Image: DIG_E_2013_Fine_Lines_022_PS4.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2013)

Fine Lines: American Drawings from the Brooklyn Museum, Friday, March 08, 2013 through Sunday, January 18, 2015 (Image: DIG_E_2013_Fine_Lines_023_PS4.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2013)

Fine Lines: American Drawings from the Brooklyn Museum, Friday, March 08, 2013 through Sunday, January 18, 2015 (Image: DIG_E_2013_Fine_Lines_024_PS4.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2013)

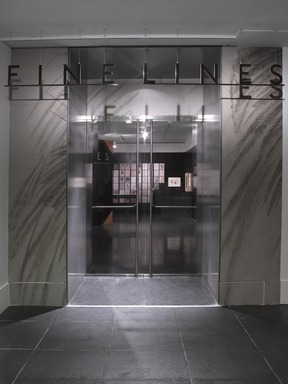

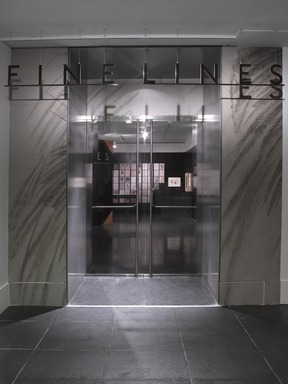

Fine Lines: American Drawings from the Brooklyn Museum

-

Fine Lines: American Drawings from the Brooklyn Museum

Fine Lines: American Drawings from the Brooklyn Museum, the first major presentation of the Museum’s most significant drawings and sketchbooks, showcases the variety and vitality of the graphic arts in the United States between the late eighteenth and the mid-twentieth century. Throughout this period and into the present day, drawing has held an important place in American art. Artists have used drawing as a way of recording the world around them, as an expression of a creative impulse, as preparation for work in other formats, as a vehicle for artistic experimentation, and as an autonomous form of art. Long regarded as the foundation for all other forms of art (including painting, sculpture, and architecture), drawing has been a pillar of artistic training and a fundamental part of the creative process for many American artists. In addition, drawings have a powerful sense of intimacy and immediacy because of their close connection to the artist’s hand.

Fine Lines features more than a hundred drawings and sketchbooks in a wide range of media, subject matter, styles, and practices within the history of American graphic arts. The works are arranged thematically in sections devoted to the human body, costume studies, portraiture, narrative subjects, the landscape, and urban imagery. In addition, a technical section about conservation investigates the distinctive properties of a variety of materials and techniques, shedding light on how artists achieved certain effects. Altogether, this presentation of master drawings from the Museum’s collection affords a rare opportunity to appreciate remarkable works that are infrequently exhibited because of their light sensitivity and fragility. -

Recording Anatomy

The human body has long been considered one of the most challenging subjects for the artist. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, mastering the representation of the figure was a fundamental component of professional training. In art academies, students learned to depict the body by drawing from casts of classical sculpture—regarded as embodying Western ideals of physical perfection—and from live models. Even as progressive artists began to reject the conventional practices and idealized naturalism of academic art in the late nineteenth century, the nude figure maintained a vital presence in American art. Artists used the body to explore new styles and shifting conceptions about the nature of human physicality.

The drawings in this section range from figure studies that reflect the enduring legacy of the academic tradition, to works that take a frank and realistic approach to the nude, to modernist experiments with form and the expressive potential of the human body. -

Fashioning Character

Costume drawings have long served important and multifaceted roles in American art. Some were created as technical exercises for working out the illusionistic fall of drapery over the human figure. In the academic curriculum, artists advanced from representing the nude body to portraying the clothed form.

In figural representation, costume also adds a layer of narrative content. In other words, artists used distinctive clothing and other accessories to construct or fashion a character’s identity. Nostalgic images of peasants and rural folk became popular over the course of the nineteenth century as the United States became increasingly urbanized and industrialized. American artists and audiences were also fascinated with the “exotic” and the “picturesque,” finding a range of interesting character types in far-off lands, as well as closer to home in a transformed modern society. -

Portraying Personalities

The nature of drawing makes it well suited to portraiture, an important genre throughout the history of American art. A portrait drawing can often be made with more ease, speed, and economy than an oil painting or a sculpture, and graphic media can achieve a wide range of pictorial effects. The intimacy of a drawing also enhances the sense of immediacy evoked by the portrait.

The drawings in this section include images of specific individuals, idealized depictions of generalized types, and symbolic or emblematic portraits. Most of these works appear in a conventional bust-length format, capitalizing on the age-old assumption that the face is the most expressive and idiosyncratic part of the body. As a representation of an individual, a portrait functioned not only to record a likeness but also to signify social identity, moral character, mood, and personality. Many artists adopted a naturalistic style to convey a sitter’s distinctive appearance, while others used idealization or abstraction, or included symbolic elements to capture a person’s character. -

Telling Tales

The drawings in this section relate stories through a combination of characters, setting, and action. Narrative pictures present the artistic challenge of conveying an anecdote through pictorial means in a way that is both easily legible and aesthetically engaging. In traditional academic training, artists advanced from figure drawing to multifigural compositions in the Grand Manner, with subjects drawn from history, religion, and literature. Drawings played an important role as preparatory studies for the orchestration of pose, gesture, lighting, and other components in these complex narrative paintings.

Over the course of the nineteenth century, artists often found anecdotal interest in genre scenes of everyday life and used drawings to capture their observations. With the expansion of the publishing industry in this period, many artists worked in commercial illustration, making images to accompany stories in magazines, newspapers, and books.

In these diverse types of narrative drawings—preparatory academic studies, genre subjects, and popular illustrations—artists generally used a style rooted in naturalism to convey their tales clearly, while still manipulating formal elements and revealing details for expressive effect. -

Exploring Nature

The easy portability of drawing materials has historically made this art form well suited to documenting nature through on-the-spot observation. Ranging from panoramic vistas to close-up studies of particular species of flora or fauna, the drawings in this section exemplify various approaches to plein air (open air) sketching.

The rise of the Hudson River School in the second quarter of the nineteenth century established landscape as a significant genre in American art and placed a premium on the direct study of nature. Many artists spent the summer months working outdoors, recording their observations in drawings that were used as source material for paintings made later in the studio.

Plein air sketching remained a vital practice into the twentieth century. Influenced by the French Barbizon School, Impressionism, and other modern movements, artists sought to portray the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere as well as their subjective responses to nature. In addition to providing a respite from the chaos of urban life, nature inspired experiments in new styles and aesthetic concerns. -

Observing the Built Environment

For artists, the impulse to represent the world around them with on-the-spot sketches extended to both the wonders of nature and the constructions of human beings. The drawings of architectural edifices and cityscapes in this section address the structural, spatial, and aesthetic properties of built things, as well as the formal and symbolic relations between organic and synthetic forms.

Throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, depictions of historical architecture documented these structures and invited philosophical musings about the passage of time and humankind’s transformation of the natural world. As the United States developed into a more urbanized and industrialized society during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, artists found aesthetic inspiration in the new vertical thrust of skyscrapers and the gridded geometries of cities and mechanical forms. The dramatically altered landscape of the modern metropolis prompted artists to seek new ways of capturing the urban environment and experience through modern and abstract styles. -

Drawing Materials and Techniques: The Conservator's View

Fine Lines gave conservators the opportunity to study many drawings that had not been exhibited for decades. Each work was examined to understand how the artist created it and to assess its condition. Some objects look much the way they did when first made, whereas others have changed over time. After gaining a greater understanding of the condition of the drawings, the conservators, in conjunction with the curators, decided on a course of treatment to preserve each piece.

A large part of the conservator’s work involves examining the drawing materials and paper. Identifying materials can often help to date works and place drawings within a historical context. Many more materials became available to American artists beginning in the late eighteenth century, owing to scientific advances and increased trade with England after the Revolutionary War. Greater exposure to European artists and artworks stimulated interest in the art of drawing, and numerous art treatises and instruction manuals encouraged its study as a valuable component of a well-rounded education. -

Behind the Scenes in the Conservation Laboratory

Conservation treatments are generally performed to correct changes that occurred in the past or to help prevent further changes in the future. In some cases the goal is to bring the drawing closer to its original appearance. Decisions regarding treatment are made after careful examination of each work and in consultation with the curators. -

Historical Drawing Manuals and Treatises

Today someone interested in learning to draw might take an art class or watch a video on YouTube. In the past, many artists obtained their instruction from books. As drawing became more of a popular artistic discipline in the nineteenth century, thousands of copies of drawing manuals and treatises were sold. These books gave aspiring artists lists of necessary artistic materials, as well as exercises for developing their drawing skills. Treatises provided discourses and instructions on topics ranging from the correct way to hold a pencil, to how to draw different types of lines, to techniques for drawing specific subjects such as the human figure or trees. -

Marks on Paper

Many types of papers, finished in a range of thicknesses, tints, and textures, were produced specifically for artists’ use beginning in the early nineteenth century. This case contains various drawing materials applied to two different sheets—a rough example and a smooth one—to illustrate how the artist’s choice of paper changed the look of the work.

The appearance of drawing materials was also influenced by the instrument used—whether a brush or a pen, a sharp or a dull point—and the amount of pressure applied by the artist’s hand. In addition, the hardness, hue, and blackness of materials varied according to the amount of wax, chalk, or black pigment added to the formula. -

Up Close

As seen here, photographs taken under magnification can help to identify paper and materials, and to reveal the artist’s working method. Some materials, such as charcoal, chalk, and Conté crayon, can appear similar to the naked eye but look different under the microscope. Magnification is also useful to ascertain the fragility of the media; a powdery, soft surface will require special framing materials and specific travel restrictions. -

Drawing Instruments from the Past

The pencils, pastels, and charcoal that are available in art stores today look similar to those of the past, but some instruments, such as ink pens, have changed as technology has improved. Quill pens were used for writing and drawing for centuries. The artist could cut the tip of the quill pen into different shapes to create various types of lines. It would last about one day before it needed to be resharpened with a penknife. Reed pens, also cut by hand, could be used for bold, broad strokes. These implements were slowly replaced by the steel-nibbed pen, first made in 1825 in England, and the fountain pen, whose internal ink reservoir made an inkwell unnecessary. Artists’ manuals often included advice on choosing, preparing, and customizing materials and equipment. -

Laid and Wove Paper

Two types of paper, distinguished by the method of manufacture. Laid paper has a gridlike pattern, caused by the wires of the paper mould on which it is made. Wove paper, available by the end of the eighteenth century, is made on a fine mesh screen and therefore lacks the grid pattern of laid paper. The grid pattern—or its absence—is often visible when a sheet is held up to the light. -

Charcoal

A medium made by burning thin sticks of wood in an airtight container. By the mid-nineteenth century, charcoal particles were often compressed into a stick and called compressed charcoal. -

Chalk

A natural material mined from the earth composed of calcium carbonate (white) and carbonaceous shale (black). Chalk was replaced in the nineteenth century by fabricated media such as Conté crayon and fabricated chalk. -

Ink

A liquid medium generally applied with a pen or brush.

Black ink: A black pigment mixed with water and sometimes animal glue or gums.

Sepia ink: An ink made from the ink bladder of a cuttlefish.

Bister: A transparent, warm-colored ink, commonly applied with a brush, made from wood soot.

Iron gall ink: A common writing ink since antiquity, made from oak-tree galls and iron salts, used mostly with a pen and an ink pot. The ink is often corrosive. -

Graphite

A natural material made of carbon, first mined in Borrowdale, England, in the sixteenth century. Originally, pieces of graphite were cut and trimmed to fit inside hollow wood casings to make sticks. Today, the graphite in artists’ pencils is combined with clay and other additives and then fired. -

Conté Crayon

A fabricated material made of powdered graphite mixed with clay and pigments and baked, invented in France in 1795. -

Pastel

A medium in stick form composed of colored pigments with white chalk and a small amount of gum binder. -

Erasers

Tools used to remove media, both to correct mistakes and to create highlights. Rubber erasers, bread crumbs, chamois cloths, stumps, and scrapers were all employed for these purposes.

-

November 1, 2012

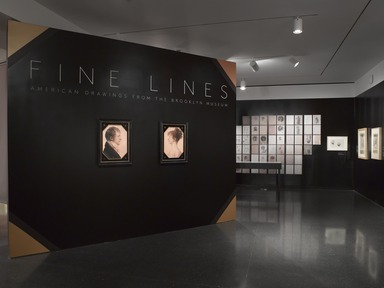

Fine Lines: American Drawings from the Brooklyn Museum presents a selection of more than a hundred rarely seen drawings and sketchbooks produced between 1768 and 1945 from the Brooklyn Museum’s exceptional collection. The exhibition will feature the work of more than seventy artists, including John Singleton Copley, Stuart Davis, Thomas Eakins, William Glackens, Marsden Hartley, Winslow Homer, Edward Hopper, Eastman Johnson, Georgia O’Keeffe, John Singer Sargent, and Benjamin West. Among the works on display will be Gaston Lachaise’s Back of a Nude Woman (1929), Winslow Homer’s Two Girls in Field (1871), and William Merritt Chase’s Shinnecock Hills (circa 1895). Investigating the place of drawing within the broader history of American art before 1945, Fine Lines showcases a variety of subjects, styles, and practices and demonstrates the variety and vitality of the graphic arts in America across nearly two centuries.

The exhibition provides insights into why artists draw through a range of works: carefully transcribed anatomical, portrait, and nature studies; preparatory drawings; quick sketches capturing an artist’s impressions; and highly finished compositions made for display or reproduction. Organized into six thematic categories, Fine Lines draws comparisons among artists of diverse periods and artistic approaches. The exhibition includes one section on portraiture and two sections on the human figure: one focusing on the nude, and the other examining the clothed figure. A section considers narrative subjects and how artists craft a story through the integration of figures, objects, and setting. Natural and urban environments are the focus of two landscape sections. An additional conservation section investigates the distinctive properties of a variety of graphic materials and techniques.

Fine Lines: American Drawings from the Brooklyn Museum is organized by Karen A. Sherry, formerly Associate Curator of American Art, Brooklyn Museum. It is accompanied by a catalogue, published by the London-based firm D Giles Ltd. in association with the Brooklyn Museum, that is the first major publication on the Museum’s holdings of pre-1945 American drawings. The hardcover retails for $59.95; the softcover, exclusively available at the Museum, retails for $42.00.

Generous support for this exhibition and the accompanying catalogue was provided by Leonard and Ellen Milberg. Additional funding for the exhibition was provided by the Robert E. Blum Fund. The catalogue was also supported by Linda E. Scher; Furthermore: a program of the J. M. Kaplan Fund; and a Brooklyn Museum publications endowment established by the Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Foundation and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

Press Area of Website

View Original