Rachel Kneebone: Regarding Rodin, January 27, 2012 through August 12, 2012 (Image: DIG_E_2012_Rachel_Kneebone_01_PS4.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2012)

Rachel Kneebone: Regarding Rodin, January 27, 2012 through August 12, 2012 (Image: DIG_E_2012_Rachel_Kneebone_02_PS4.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2012)

Rachel Kneebone: Regarding Rodin, January 27, 2012 through August 12, 2012 (Image: DIG_E_2012_Rachel_Kneebone_03_PS4.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2012)

Rachel Kneebone: Regarding Rodin, January 27, 2012 through August 12, 2012 (Image: DIG_E_2012_Rachel_Kneebone_04_PS4.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2012)

Rachel Kneebone: Regarding Rodin, January 27, 2012 through August 12, 2012 (Image: DIG_E_2012_Rachel_Kneebone_05_PS4.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2012)

Rachel Kneebone: Regarding Rodin, January 27, 2012 through August 12, 2012 (Image: DIG_E_2012_Rachel_Kneebone_06_PS4.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2012)

Rachel Kneebone: Regarding Rodin, January 27, 2012 through August 12, 2012 (Image: DIG_E_2012_Rachel_Kneebone_07_PS4.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2012)

Rachel Kneebone: Regarding Rodin, January 27, 2012 through August 12, 2012 (Image: DIG_E_2012_Rachel_Kneebone_08_PS4.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2012)

Rachel Kneebone: Regarding Rodin, January 27, 2012 through August 12, 2012 (Image: DIG_E_2012_Rachel_Kneebone_09_PS4.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2012)

Rachel Kneebone: Regarding Rodin, January 27, 2012 through August 12, 2012 (Image: DIG_E_2012_Rachel_Kneebone_10_PS4.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2012)

Rachel Kneebone: Regarding Rodin, January 27, 2012 through August 12, 2012 (Image: DIG_E_2012_Rachel_Kneebone_11_PS4.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2012)

Rachel Kneebone: Regarding Rodin, January 27, 2012 through August 12, 2012 (Image: DIG_E_2012_Rachel_Kneebone_12_PS4.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2012)

Rachel Kneebone: Regarding Rodin

-

RACHEL KNEEBONE Regarding Rodin

This exhibition sets up a thematic and visual dialogue between new works by the British artist Rachel Kneebone and iconic works by the nineteenth-century French master Auguste Rodin (1840–1917). This pairing brings together the Brooklyn Museum’s exceptional Rodin collection, a gift of the Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Foundation in 1984, and the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art, which is dedicated to presenting art that addresses feminist issues from a range of historical perspectives. The exhibition highlights the interest shared by two artists born more than 130 years apart in exploring and representing the human experiences of sexuality, desire, loss, and despair through figurative sculpture. The conversation between these creative voices continues the Brooklyn Museum’s commitment to fostering expanded readings of works of art across traditional collections and historical boundaries.

Kneebone’s work engages directly with the histories of art and literature. She regularly draws her titles from literary and biblical sources, and was particularly influenced by the work of the poet Rainer Maria Rilke, who served as Rodin’s secretary, in choosing the thematic pairings of artworks and quotations for this presentation. Her formal allusions to the history of sculpture, including genres such as funerary statuary, commemorative monuments, and triumphal towers, have led to comparisons with artists ranging from Michelangelo to Louise Bourgeois, but this exhibition marks the first time Kneebone’s work has been presented alongside one of her important historic referents.

Rodin, who stated that “sculpture is the art of the hole and the lump,” made daring use of negative spaces and rough-hewn surfaces. These techniques are also characteristic of Kneebone’s work, and they invite metaphorical readings that allude to the hole, or the absence of the phallus, that defines womanhood in Freudian thought and to the biblical lump of earth that gave birth to Adam. These multiple points of reference within both artists’ work—from the art of modeling figures to the psychosexual formation of the individual—are the focus of Rachel Kneebone: Regarding Rodin.

Catherine J. Morris

Curator, Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art -

REPETITION AND PROCESS

The inner life that makes up this age is formless and intangible; it is, in short, in flux.... [Rodin] took hold of everything that was vague, developing, and constantly changing—all of which was in him too—and gave form to it.

—Rainer Maria Rilke, Auguste Rodin, 1902

A fluidity of thought imbues my practice with an almost photographic quality, making permanent through material a moment; capturing what is always, and can only ever exist, in a state of flux.

—Rachel Kneebone, 2011

In their smaller works, one can appreciate how Rodin’s and Kneebone’s chosen materials dictate their working processes, and how repetition plays very different roles in their respective oeuvres. Rodin’s The Burghers of Calais, First Maquette shows the sculptor roughly working out ideas in clay for a large bronze memorial. Rodin arrived at his final composition after numerous rounds of experimentation, but because these clay models were also cast as bronze multiples, his process ultimately produced an array of repeated or slightly modified Burghers. Kneebone’s works, on the other hand, are always unique, because porcelain sculpture cannot be cast in editions. Nevertheless, within each piece and within her practice, there is a compulsive repetition, exemplified by the profusion of figures, body parts, and organic matter seen in When I doubt I exist again. Thus, despite working in a medium that arrests movement, both artists incorporate flux and mutation into their artistic processes. -

EXPRESSION AND THE BODY

No part of the body was insignificant or trivial, for even the smallest of them was alive. Life, which appeared on faces with the clarity of a dial, easily read and full of signs of the times, was greater and more diffuse in bodies, more mysterious and more eternal. —Rainer Maria Rilke, Auguste Rodin, 1902

Recently I have taken to isolating limbs, the torso. Why am I blamed for it? Why is the head allowed and not portions of the body? Every part of the human figure is expressive.

—Auguste Rodin, interview in The Englishwoman, April 1910

In works such as Mine heart is turned within me and Eyes that look close at wounds themselves are wounded, both from her Lamentation series, Kneebone seeks to produce the same pathos and visceral connection that Rodin introduced into modern memorial sculpture more than a century earlier with his The Burghers of Calais. Mourning, loss, and despair—experiences of the most profound and universal nature—find their expression here through the body. The Burghers was controversial in its time for showing the struggle that accompanied self-sacrifice, thereby honoring heroism as the product of a difficult human choice rather than as a superhuman capacity. In Eyes that look close, a traditional shroud of mourning hoods a seated figure resembling the Madonna in Michelangelo’s Pietà, but the body beneath the garment is an amorphous mass of organs and orifices, projecting strength and vulnerability at the same time. -

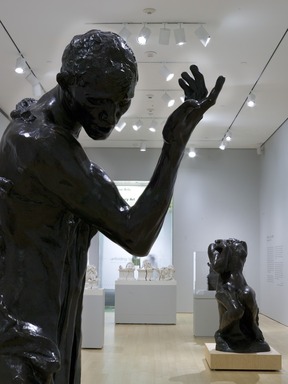

MASTERY AND MONUMENTALITY

This was a man whose eyes needed nothing; had the world been empty, he would have filled it with his gaze.... This was Creation itself, in all its presumption, arrogance, frenzy, and ecstasy, making use of Balzac to appear in this form.

—Rainer Maria Rilke, Auguste Rodin, 1902

I know I will never make a definitive work; sometimes I think—at best—I aim for a “triumphant failure.”

—Rachel Kneebone, 2011

Here Rodin’s proud, naked figure of the realist French novelist Honoré de Balzac appears alongside Kneebone’s two newest works, The Paradise of Despair and For Beauty’s nothing but beginning of Terror we’re still just able to bear. In these large-scale towers covered with writhing forms, Kneebone combines and subverts two conventions of sculpture: the triumphal column, a classical monument to military victory dating back to ancient Rome, and the theme of the male artist’s generative power, often associated with phallic iconography and metaphors of sexual virility. In The Paradise of Despair, the two traditions are twisted together, undermining or parodying the fantasy of military invincibility and artistic mastery inherent in these cultural precedents. Headless bodies climb the base to join a teeming mass, but rather than ascending to great heights, they fall back, a jumbled heap of arms and legs, suggesting both orgiastic frenzy and corpses piled up after battle. -

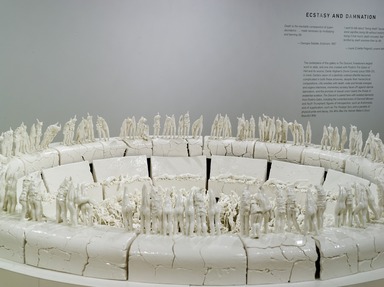

ECSTASY AND DAMNATION

Death is the inevitable consequence of superabundance . . . made necessary by multiplying and teeming life.

—Georges Bataille, Eroticism, 1957

I want to talk about “loving death” because this alone signifies loving life without restriction, loving it that much, death included. Not being terrified by death anymore than by life.

—Laure (Colette Peignot), unsent letter, 1936

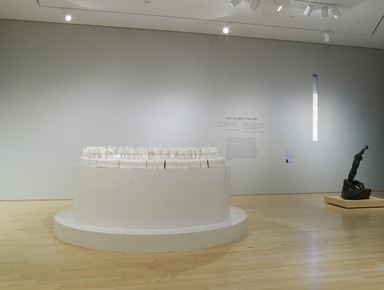

The centerpiece of this gallery is The Descent, Kneebone’s largest work to date, and one she created with Rodin’s The Gates of Hell and its source, Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy (circa 1308–21), in mind. Dante’s vision of a carefully ordered afterlife becomes complicated in both these artworks, despite their hierarchical compositions. Life wrestles with death, male and female energies and organs intertwine, momentary ecstasy faces off against eternal damnation, and the promise of sexual union meets the threat of existential isolation. The Descent is paired here with isolated elements from Rodin’s Gates, including the contorted lovers of Damned Women and Youth Triumphant; figures of introspection, such as Andromeda, and of supplication, such as The Prodigal Son; and a parable of physical pride and decay, She Who Was the Helmet Maker’s Once- Beautiful Wife.

-

November 1, 2011

Rachel Kneebone: Regarding Rodin, an exhibition featuring new works by the British artist Rachel Kneebone shown alongside iconic works from the nineteenth-century French master Auguste Rodin, will be on view January 27 through August 12, 2012 in the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art. Kneebone’s first major museum presentation, the exhibition will include eight intricately wrought, large-scale porcelain sculptures paired with fifteen Rodin sculptures from the Brooklyn Museum’s collection.

Rachel Kneebone: Regarding Rodin will focus on Kneebone’s and Rodin’s shared interest in the examination of gender and sexuality, the nature of sculptural form, and the formal representation of mourning, ecstasy, death, and vitality in figurative sculpture. This pairing will also offer a visual comparison of their sculptural materials and processes. Kneebone’s porcelain sculptures make reference to the history of sculpture including comparisons to Michelangelo, Gianlorenzo Bernini, and Louise Bourgeois. Her simultaneously pristine and agitated artworks, which integrate human forms that merge into odd mutations, provide a stark contrast to Rodin’s heavy, dark, yet equally animated bronzes. Whereas Rodin cast his sculpture, Kneebone creates unique artworks that she fires in a small kiln in her studio. Her larger sculptures are fired in sections and then assembled later into completed pieces.

This exhibition marks the first time that Kneebone will present her artwork along with one of her significant historical referents. The centerpiece of the exhibition and the largest work that she has created to date, The Descent (2008), was inspired by Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy, as was Rodin’s masterpiece The Gates of Hell (1880–1917). The Descent is a highly theatrical sculpture consisting of hundreds of hybrid figures tumbling into an abyss of teeming with bodies and flesh. Both Kneebone’s and Rodin’s sculptures take thematic inspiration from The Inferno, the first section of the Divine Comedy, and highlight the charged emotion and the tensions that emerge from life wrestling with death and momentary ecstasy mixed with eternal suffering.

Kneebone was born in 1973, in Oxfordshire, England, and graduated in 1997 from University of The West of England, Bristol. In 2004, Kneebone graduated with an M.A. in sculpture from the Royal College of Art, London. She currently lives and works in London.

Born in Paris in 1840, Auguste Rodin is often considered the founder of modern sculpture. The Brooklyn Museum’s collection includes well-known masterpieces such as The Age of Bronze, The Burghers of Calais, The Gates of Hell, and the Monument to Balzac. The Rodin collection was generously gifted to the Brooklyn Museum in 1984 by the Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Foundation.

Rachel Kneebone: Regarding Rodin is organized by Catherine Morris, Curator of the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art, Brooklyn Museum. The fully illustrated catalogue, Lamentations, published by White Cube gallery in 2010, will accompany the exhibition. This exhibition has been supported by the Elizabeth A. Sackler Foundation.

Press Area of Website

View Original