American High Style: Fashioning a National Collection

1 of 10

To mark the new relationship between the Brooklyn Museum and the Costume Institute at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Brooklyn Museum presents an exhibition of some of the most renowned objects from its costume collection. American High Style consists of approximately eighty-five dressed mannequins and a selection of hats, shoes, sketches, and other fashion-related material that will reintroduce the collection, long in storage, to the public. The exhibition is organized in groups representing the most important strengths of the collection. Works by the first generation of American women designers such as Bonnie Cashin, Elizabeth Hawes, and Claire McCardell are featured, as well as material created by Charles James, Norman Norell, Gilbert Adrian, and other important American designers. Also included are works by French designers who had an important influence on American women and fashion, such as Charles Frederick Worth, Elsa Schiaparelli, Jeanne Lanvin, Jeanne Paquin, Madeleine Vionnet, and Christian Dior. The Metropolitan Museum of Art will celebrate the arrival of the Brooklyn Museum costume collection at the Met with a related exhibition, American Woman: Fashioning a National Identity, on view May 5–August 15, 2010.

American High Style: Fashioning a National Collection is supported by Lisa and Dick Cashin, Barbara and Richard Debs, Cheryl and Blair Effron, Arline and Norman M. Feinberg, Stephanie and Tim Ingrassia, Barbara and Richard Moore, Martha A. and Robert S. Rubin, and Barbara M. and John L. Vogelstein.

Media sponsor

Online media sponsor

Organizing department

Special Exhibition

Media

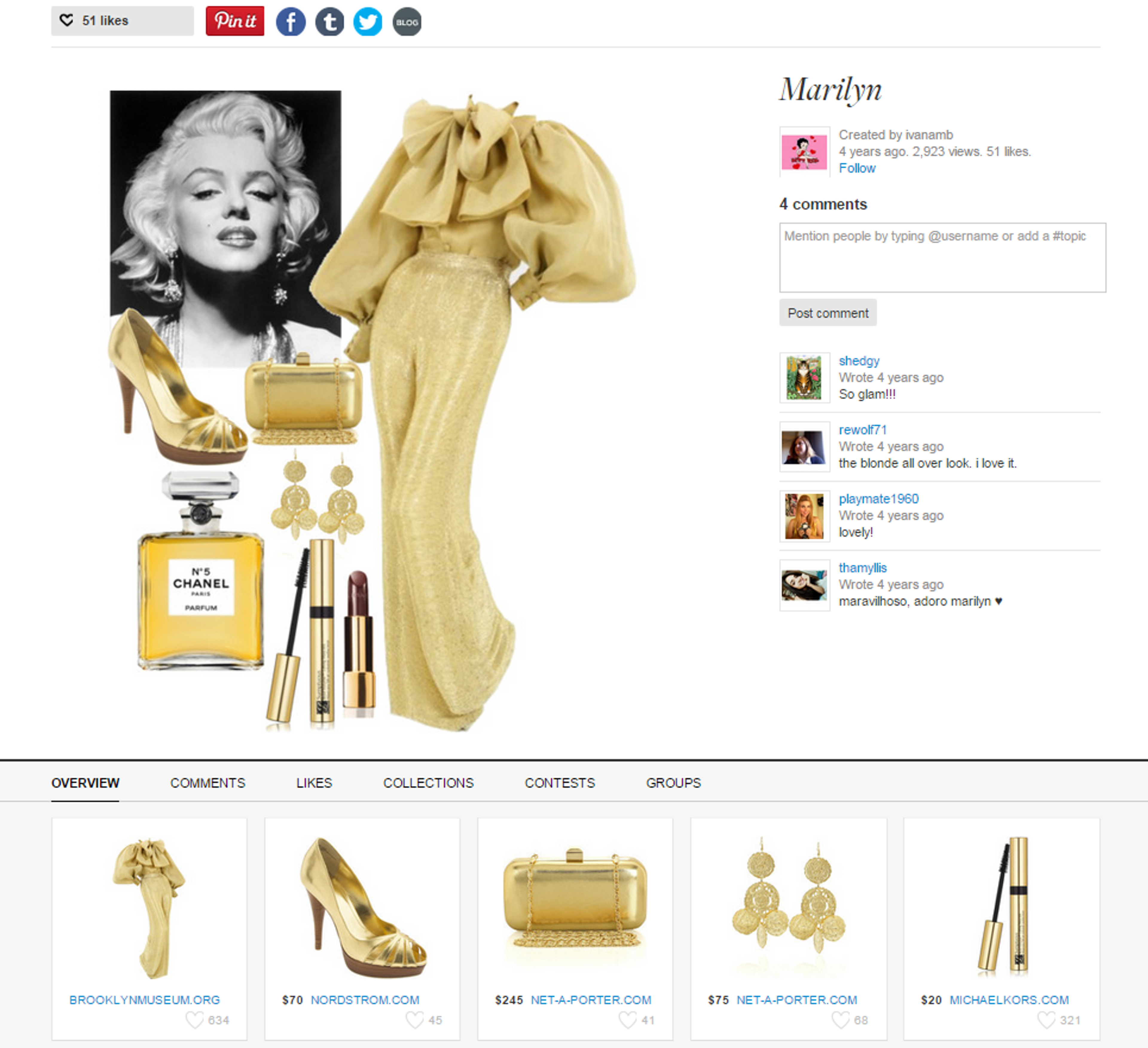

During the exhibition, Web and gallery visitors remixed fashions from American High Style using Polyvore’s virtual styling tool.