Tiraz: Nine Early Islamic Textiles

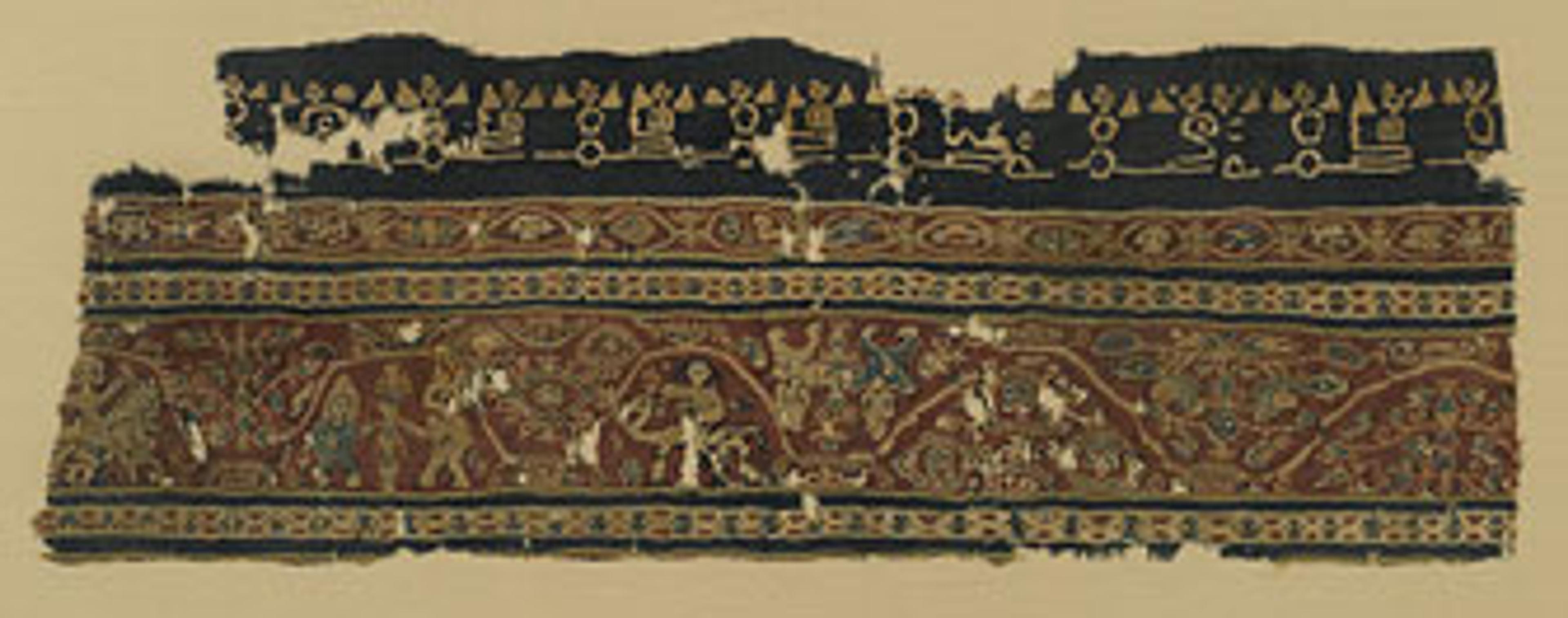

This focused installation of works rarely on view includes nine of the Museum’s most exquisite tiraz textile fragments and an important pictorial Iranian ceramic. Derived from the Persian word for embroidery, the term tiraz refers to a kind of textile originally produced as a gift of honor from the earliest rulers of the Islamic world as well as to the special factories that produced these textiles. Often, tiraz textiles were inscribed with the names, reign dates, and praises of the ruler who ordered their production, and have thus provided scholars with invaluable historical information.

The nine textiles on view, mostly from North Africa, are breathtaking in their range of style and decoration, from austere examples with black-on-white embroidered inscriptions to textiles depicting animals and human figures. Included in the installation is a fragment from the earliest datable textile from the Islamic world, containing the name of the Umayyad caliph Marwan II (reigned 744–50). The exhibition is presented in conjunction with Tree of Paradise: Jewish Mosaics from the Roman Empire.

Organizing department

Arts of the Islamic World