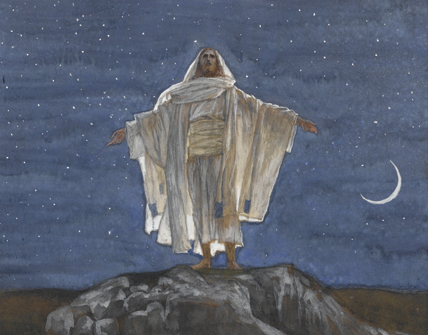

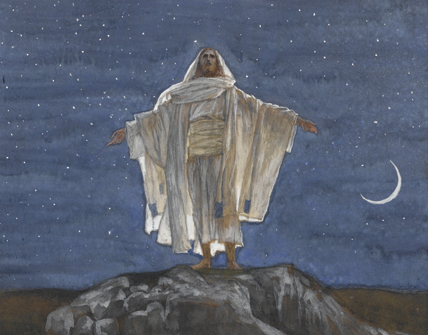

James Tissot (French, 1836−1902). Jesus Goes Up Alone onto a Mountain to Pray (detail), 1886−94. Opaque watercolor over graphite on gray wove paper, 1138 x 61⁄4 in. (28.9 × 15.9 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Purchased by public subscription, 00.159.137

James Tissot (French, 1836−1902). Jesus Goes Up Alone onto a Mountain to Pray (detail), 1886−94. Opaque watercolor over graphite on gray wove paper, 1138 x 61⁄4 in. (28.9 × 15.9 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Purchased by public subscription, 00.159.137

James Tissot (French, 1836–1902). What Our Lord Saw from the Cross, 1886–94. Opaque watercolor over graphite on gray-green wove paper, 93⁄4 x 91⁄6 in. (24.8 × 23 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Purchased by public subscription, 00.159.299

In the most memorable, and even notorious, of Tissot’s biblical images, Christ looks out at the crowd of spectators arrayed before him: Mary Magdalene, in the immediate foreground, with her long red tresses swirling down her back, kneels at his feet, which are clearly visible at the bottom center of the composition. Beyond her, the Virgin Mary clutches her breast, while John the Evangelist looks up with hands clasped.

The artist here adopted the point of view of Christ himself. Few painters have conceived a composition this daring. In his audacity, however, Tissot remained true to his artistic vision for the series: ultimately, the image is an exercise in empathy. Its point is to give viewers, accustomed to looking at the event from the outside, a rare opportunity to imagine themselves in Christ’s place and consider his final thoughts and feelings as he gazed on the enemies and friends who were witnessing, or participating in, his death.

James Tissot (French, 1836–1902). The Daughter of Herodias Dancing, 1886–96. Opaque watercolor over graphite on gray wove paper, 95⁄16 x 75⁄16 in. (23.7 × 18.6 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Purchased by public subscription, 00.159.131

Although Herod had imprisoned John the Baptist for speaking against his marriage to Herodias, the ruler admired the Baptist as a wise and righteous man. On the occasion of Herod’s birthday, Salome, the daughter of Herodias, danced before the guests, pleasing the host so much that he promised her anything she wanted. To Herod’s dismay, the young woman, following her mother’s wish, demanded the head of John the Baptist on a platter. Although loathe to kill the Baptist, Herod acceded to this request.

In a commentary, Tissot noted that he found inspiration for his image of Salome’s acrobatic dance in ancient reliefs from sources as diverse as Egypt, India, and Persia as well as the reliefs of the Cathedral of Rouen in his native France.

James Tissot (French, 1836–1902). Jesus Sits by the Seashore and Preaches, 1886–96. Opaque watercolor over graphite on gray wove paper, 103⁄16 x 79⁄16 in. (25.9 × 19.2 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Purchased by public subscription, 00.159.109

For this scene, Tissot directly integrated one of the motifs from his extensive sketching campaigns in the Middle East into a finished composition for the Gospel narrative. Here, a large boulder that the artist had drawn by the Sea of Tiberias becomes the rock on which Jesus sits as he preaches to his followers.

Such direct correlations between the sketched motif and the Gospel narrative evoke Tissot’s claim for what he termed hyperaesthesia—a combination of direct observation of his surroundings and mystical revelation. In the introduction to his illustrated Bible, he claimed: “It is in the Holy Land itself … that the mind is best attuned alike to receive and grasp the significance of every impression…. I felt that a certain receptivity was induced in my mind which so intensified my powers of intuition, that the scenes of the past rose up before my mental vision in a peculiar and striking manner…. I meditated on any special incident in its own particular sanctuary, and was thus brought into touch with the actual setting of every scene, the facts I was anxious to evoke were revealed to me.…”

James Tissot (French, 1836–1902). Healing of the Lepers at Capernaum, 1886–94. Opaque watercolor over graphite on gray wove paper, 111⁄4 x 63⁄16 in. (28.6 × 15.7 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Purchased by public subscription, 00.159.89

This Gospel episode reveals Jesus’ concern for the outcasts of society: in this case, those afflicted with leprosy, a chronic disease. The leper kneels in the center foreground of the image—dramatically making his plea to Jesus with his bandaged arms upraised. Referring to ancient laws regarding the lepers, Tissot wrote in his commentary that the man occupies the center of the road to permit the healthy to pass with ease on either side of the path.

Jesus not only healed the afflicted man but also contravened the laws regarding the “impure.” In the Gospel text, Jesus later urges the healed man to keep quiet about the specifics of the miracle but to seek the priests, to acknowledge his cure and regain his place in society and in the Temple.

James Tissot (French, 1836–1902). Jesus Ministered to by Angels, 1886–94. Opaque watercolor over graphite on gray wove paper, 611⁄16 x 93⁄4 in. (17 × 24.8 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Purchased by public subscription, 00.159.54

Following his deprivations in the wilderness, Jesus here receives the care of angels who restore his strength. Rejecting art-historical traditions in which Jesus takes material sustenance in the form of dates and pomegranates, Tissot insisted on otherworldly agency. Here blue-hued, flame-haired angels extend their fingers to touch the prostrate form of the exhausted Jesus, who appears to assume a cruciform position.

James Tissot (French, 1836–1902). The Annunciation, 1886–94. Opaque watercolor over graphite on gray wove paper, 611⁄16 x 89⁄16 in. (17 × 21.7 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Purchased by public subscription, 00.159.16

According to Saint Luke, an angel appeared to Mary and announced that she would bear the Son of God. Tissot adhered to art-historical precedents for this biblical episode, placing the Angel Annunciate at left and Mary at right. Her white robes, symbolizing purity, set her apart from the pattern-on-pattern furnishings that the artist used to signal the “authenticity” of the exotic Eastern setting. Mary sits on the floor with head bowed and hands open, humbly accepting her role.

In a later commentary in his illustrated edition of the New Testament, Tissot wrote extensively about the hierarchies and anatomies of angels. Citing biblical texts, he indicated that the cherubim, the angelic messengers he depicted in some of his images, were endowed with the face of a man and three pairs of wings: one pair to veil the face, another to cover the body, and the last used for flight on divine missions.

James Tissot: “The Life of Christ”

October 23, 2009–January 17, 2010

The exhibition James Tissot: “The Life of Christ” includes 124 watercolors selected from a set of 350 that depict detailed scenes from the New Testament, from before the birth of Jesus through the Resurrection, in a chronological narrative. It marks the first time in more than twenty years that any of the Tissot watercolors, a pivotal acquisition that entered the collection in 1900, have been on view at the Brooklyn Museum.

Born in France, James Tissot (1836−1902) enjoyed great success as a society painter in Paris and London in the 1870s and 1880s. While visiting the Church of St. Sulpice, he experienced a religious vision, after which he abandoned his former subjects and embarked on an ambitious project to illustrate the New Testament. In preparation for the work, he made expeditions to the Middle East to record the landscape, architecture, costumes, and customs of the Holy Land and its people, which he recorded in photographs, notes, and sketches. Unlike earlier artists, who had often depicted biblical figures anachronistically, Tissot painted his many figures in costumes he believed to be historically authentic, carrying out his series with considerable archaeological exactitude.

First presented in Paris in 1894, the watercolors were received with great enthusiasm, and a highly publicized exhibition later traveled to London and the United States, visiting Manhattan, Brooklyn, Boston, Philadelphia, and Chicago. In 1900, at the suggestion of John Singer Sargent, the Museum decided to acquire the series; the purchase funds were raised primarily by public subscription, spurred on, in part, by exhortations in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle newspaper urging readers to contribute to the campaign.

This exhibition has been organized by Judith F. Dolkart, Associate Curator, European Art. It is accompanied by a fully illustrated catalogue of the complete set of 350 images, published by the Museum in association with Merrell Publishers Ltd, London.

The exhibition was made possible, in part, with a generous award from the National Endowment for the Arts.