Curatorial Overview

The Dinner Party by Judy Chicago is an icon of feminist art, which represents 1,038 women in history—39 women are represented by place settings and another 999 names are inscribed in the Heritage Floor on which the table rests. This monumental work of art is comprised of a triangular table divided by three wings, each 48 feet long. Millennium runners, silk coverings inspired by altar cloths, fit over the apexes of the table. They are embroidered in white thread on a white ground, each with a subtle letter “M,” as it is the thirteenth letter of the alphabet, signifying the break in each group of place settings. Arranged chronologically along the wings are thirteen place settings; each includes a unique runner and plate, as well as a chalice, napkin, and utensils. Wing One of the table begins in prehistory with the Primordial Goddess setting and continues chronologically with the development of Judaism, to early Greek societies, to the Roman Empire, marking the decline in women’s power, signified by the Hypatia plate. Wing Two represents early Christianity through the Reformation, depicting women who signify early articulations of the fight for equal rights, from Marcella to Anna van Schurman. Wing Three begins with Anne Hutchinson and addresses the American Revolution, Suffragism, and the movement toward women’s increased individual creative expression, symbolized at last by the Georgia O’Keeffe place setting.

Genesis

Judy Chicago’s The Dinner Party began modestly, in both concept and form. From the start, her aim was “to teach a society unversed in women’s history something of the reality of our rich heritage.”1 At first, she conceived of it as a series of twenty-five china-painted plates to hang on a wall, titled Twenty-five Women Who Were Eaten Alive, a reference to the ways in which women had historically been “swallowed up and obscured by history instead of being recognized and honored.”2 Eventually, this idea expanded to include 100 abstract portraits of women on plates.

While planning the project, she visited the home of a professional china-painter who had spent several years producing an elaborate dinner service for 16 people. The settings were arranged in order on the painter’s dining room table. Chicago claims she had an epiphany at that moment, “realizing that plates are meant to be presented on a table.”3 Afterwards, she began to think of the work exclusively within the context of a table setting. The idea appealed to her on many levels because the dinner table itself carried symbolic meaning for women historically. It was the place upon which the meals women prepared were served; and it was located in the private, domestic, “feminine” space versus the public, “masculine” one.

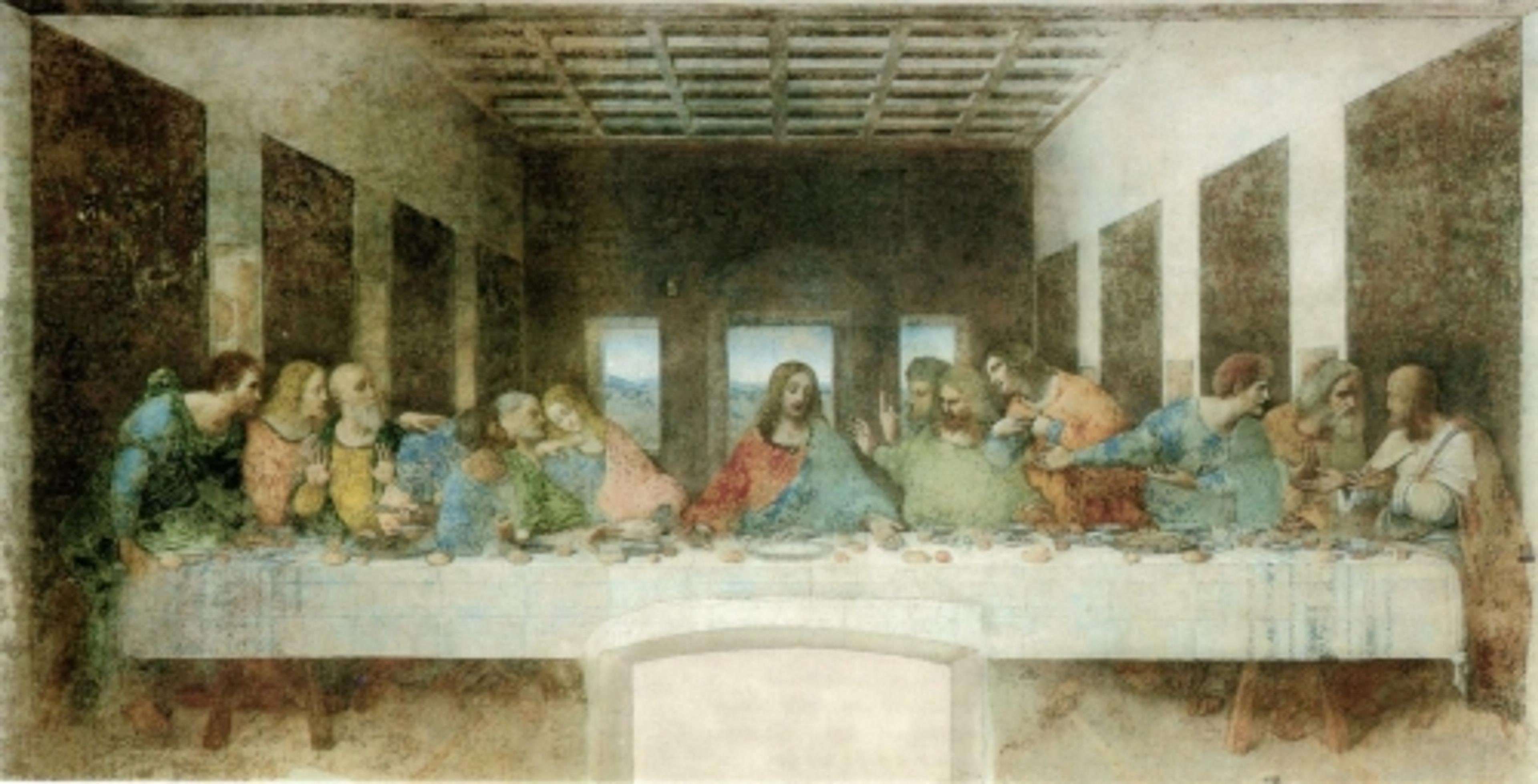

When Chicago began thinking of historical precedents for the table, she was immediately drawn to Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper, representing Christ at his last meal surrounded by his twelve disciples. As Chicago explained, “I became amused by the notion of doing a sort of reinterpretation of that all-male event from the point of view of those who had traditionally been expected to prepare the food, then silently disappear from the picture or, in this case, from the picture plane.”4 She began envisioning a reinterpretation of the canonical work with famous women as the honored guests.

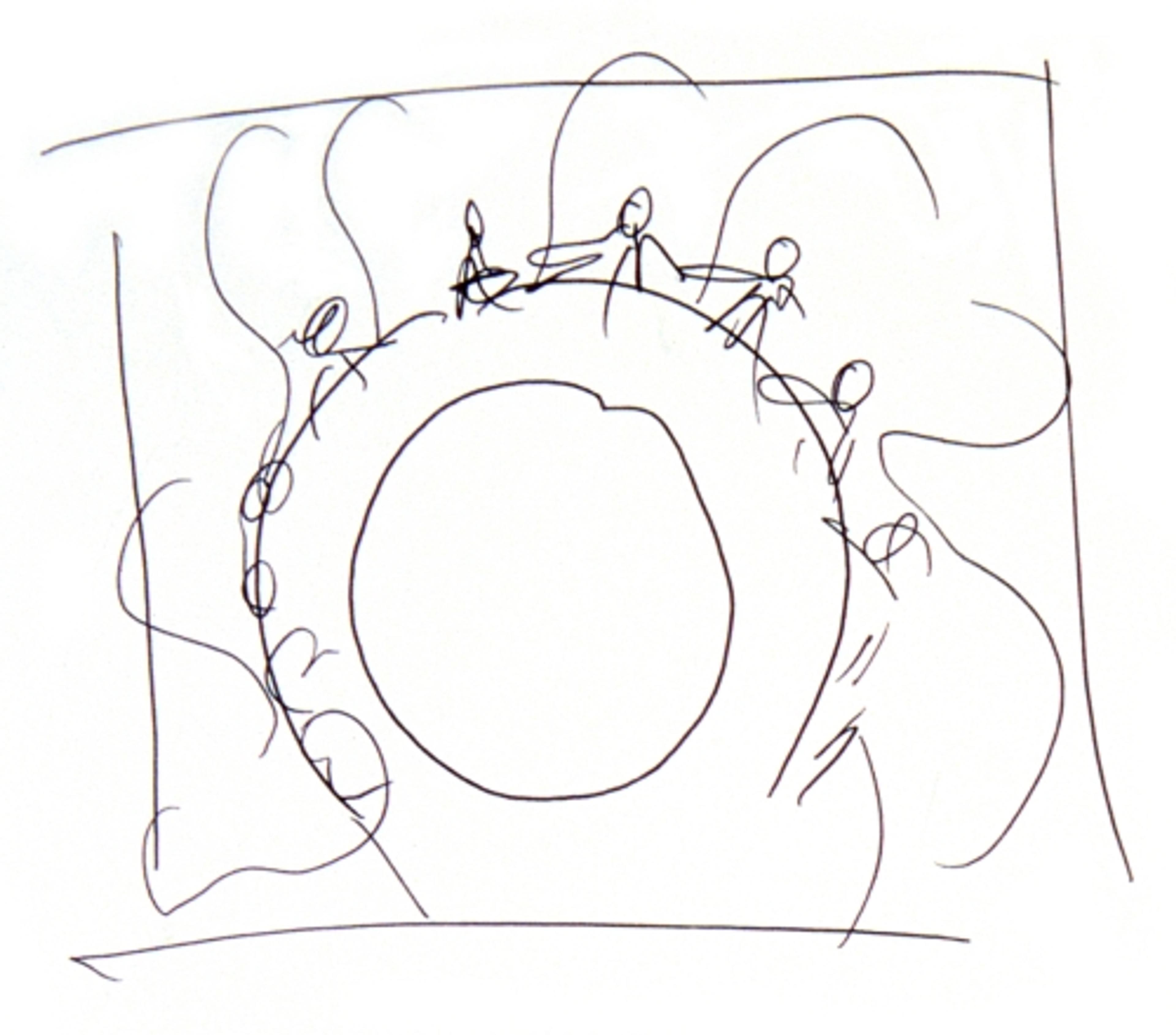

The earliest sketch in Chicago’s notebooks for The Dinner Party shows that her first idea was to have a circular table with a hollow center around which the guests would be seated. This idea was later modified to become a triangular table, a form having great significance for the artist. The equilateral triangle, interpreted by Chicago as reflecting the “goal of feminism—an equalized world,” is also a centered form recalling “one of the earliest symbols of the feminine,” and of the goddess.5 Once the shape of the table was determined, Chicago decided to place thirteen women on each side, or “wing”—thirteen to mimic the number included in The Last Supper as well as the number of women in a witches’ coven.

Notes

1. Judy Chicago, Beyond the Flower: The Autobiography of a Feminist Artist (New York: Penguin, 1997), 45.

2. Judy Chicago, The Dinner Party: A Symbol of Our Heritage (New York: Anchor Books, 1979), 8.

3. Chicago, Beyond the Flower, 46.

4. Ibid.

5. Chicago, The Dinner Party (1979 ed.), 12.

Reclamation

The Dinner Party sought to write forgotten women back into history. Its principle aim was to reclaim women from history—or his-story, as it was often referred to in the 1970s—a narrative that for millennia had excluded and even at times removed women as historical subjects.

When Chicago began researching and compiling women’s names for inclusion in The Dinner Party, she was, in many instances, starting from scratch. There were no archeologists working seriously on the history of goddess civilizations and imagery, or the all-female Amazonian societies that dated back to the 3rd and 2nd-millenia B.C.E.; there were no Egyptologists yet interested in the power of the female pharaoh Hatshepsut; there was certainly no real scholarly interest yet in the Baroque painter, Artemisia Gentileschi. Indeed, monographs on women artists were scant and works by women were very rarely on view in museums (if they owned works at all). Within this context, the archival research that went into unearthing these historical figures must be understood as groundbreaking.

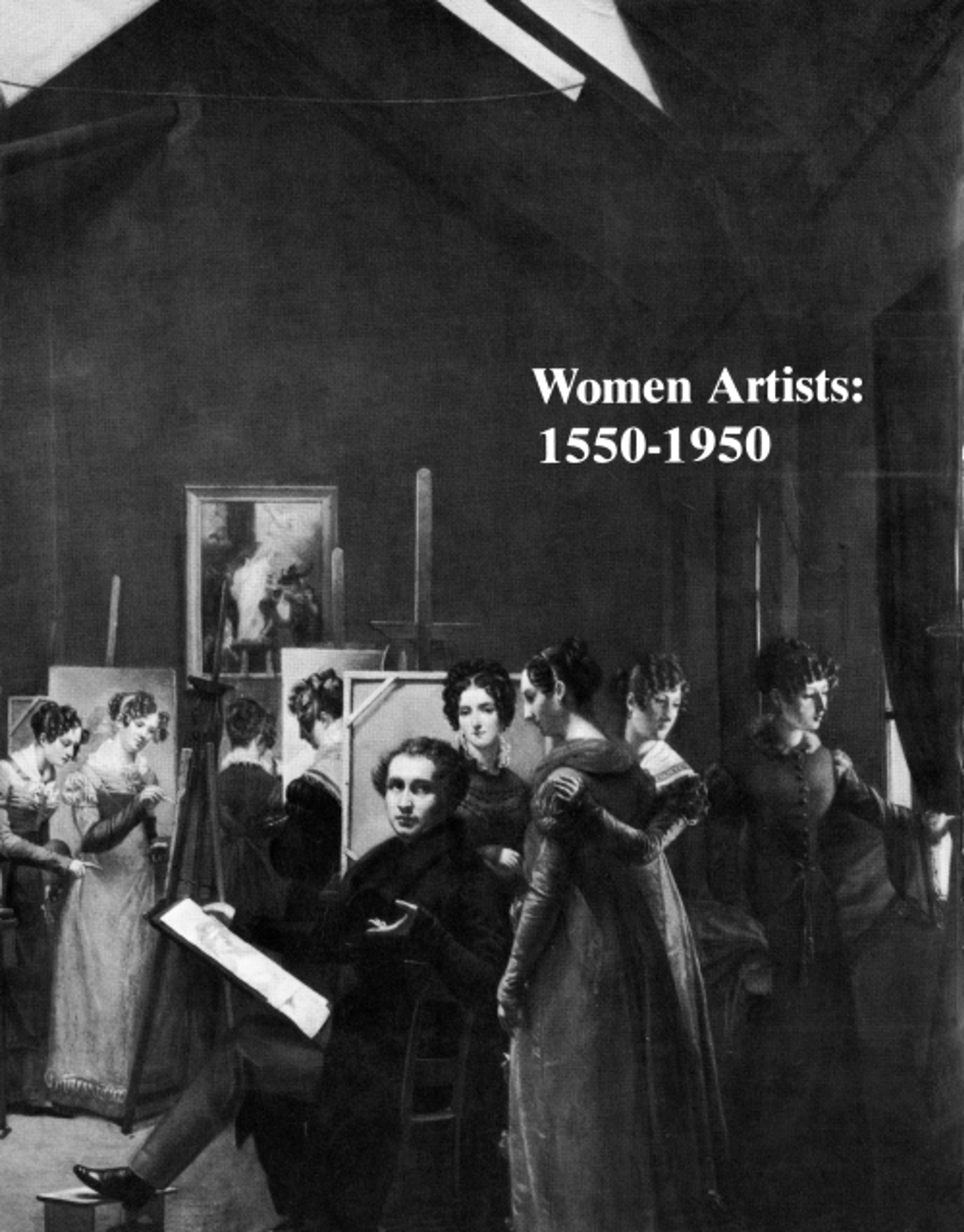

The Dinner Party is, therefore, representative of a specific moment in American history when the longstanding lack of scholarship about women was finally being addressed by an early generation of feminist scholars intent on excavating women from the archives, and criticizing his-story for its masculinist biases. This “reclamation” of women’s lost history became one of the most important feminist strategies of the 1970s, and one that resulted in new scholarship on mythological and historical female figures and societies whose names we might not otherwise know of today. For instance, in 1974 and 1975, respectively, the archeologists Marija Gimbutas and Merlin Stone presented comprehensive surveys of goddess-worshipping and matriarchal civilizations dating back to the Neolithic period (6500–3500 B.C.E.). In 1976, the art historians Ann Sutherland Harris and Linda Nochlin organized the landmark exhibition Women Artists: 1550–1950, the very first museum exhibition in this country dedicated exclusively to women artists. It was also in the 1970s that general women’s art survey books were written for the first time: Eleanor Tufts’s Our Hidden Heritage: Five Centuries of Women Artists, 1974; Elsa Honig Fine’s Women and Art: A History of Women Painters and Sculptors from the Renaissance to the 20th Century, 1978; Germaine Greer’s The Obstacle Race: The Fortunes of Women Painters and Their Work, 1979; among others.

For the first time in U.S. history, scholarly attention was being sufficiently paid to the cultural contributions of women historically, and The Dinner Party was a monumental example of its manifestation in visual form. However, the reclamation of a lost history was not the only feminist art strategy employed in The Dinner Party. There were others that, in sum, account for its power and longevity as a feminist icon, including the monumental scale of the piece; the use of “women’s work” or “craft”; and, lastly, the celebration of vaginal or “central core” imagery.

Women’s Work

Throughout the history of art, decoration and domestic handicrafts have been regarded as women’s work, and as such, not considered “high” or fine art. Quilting, embroidery, needlework, china painting, and sewing—none of these have been deemed worthy artistic equivalents to the grand mediums of painting and sculpture. The age-old aesthetic hierarchy that privileges certain forms of art over others based on gender associations has historically devalued “women’s work” specifically because it was associated with the domestic and the “feminine.” That hierarchy was radically challenged in the 1960s by Pop and feminist artists, alike (e.g., Andy Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup Can series). In the wake of the Women’s Liberation Movement, feminist artists in particular sought to resurrect women’s craft and decorative art as a viable artistic means to express female experience, thereby pointing to its political and subversive potential.

In the quest for a “female aesthetic” or artistic style specific to women, many 1970s feminist artists sought to elevate “women’s craft” to the level of “high art,” and away from its derogatory designation as “low art” or “kitsch.” As Lucy Lippard explained in her 1973 essay, “Household Images in Art,” previously women artists had avoided “‘Female techniques’ like sewing, weaving, knitting, ceramics, even the use of pastel colors (pink!) and delicate lines—all natural elements of artmaking,” for fear of being labeled “feminine artists.” The Women’s Movement changed that, she argued, and gave women the confidence to begin “shedding their shackles, proudly untying the apron strings—and, in some cases, keeping the apron on, flaunting it, turning it into art.”6 For instance, Ringgold’s handmade, narrative quilts celebrate an undervalued female creative production, just as her “Family of Woman” masks and figurines from 1970—portraits from her childhood of Mama Jones, Andrew, Barbara, and Faith—included costumes sewn by the artist’s mother, who was a professional seamstress. Likewise with Miriam Schapiro’s femmages, which she describes as “activities as they were practiced by women using traditional women’s techniques to achieve their art.”7 Schapiro viewed her use of brightly colored, patterned fabric as a conscious feminist statement. As she wrote in 1977, “I wanted to validate the traditional activities of women, to connect myself to the unknown women artists who had made quilts, who had done the invisible ‘women’s work’ of civilization. I wanted to acknowledge them, to honor them.”8 Schapiro’s femmage, like Ringgold’s narrative quilts, opened the path for the re-evaluation of anonymous art done by women.

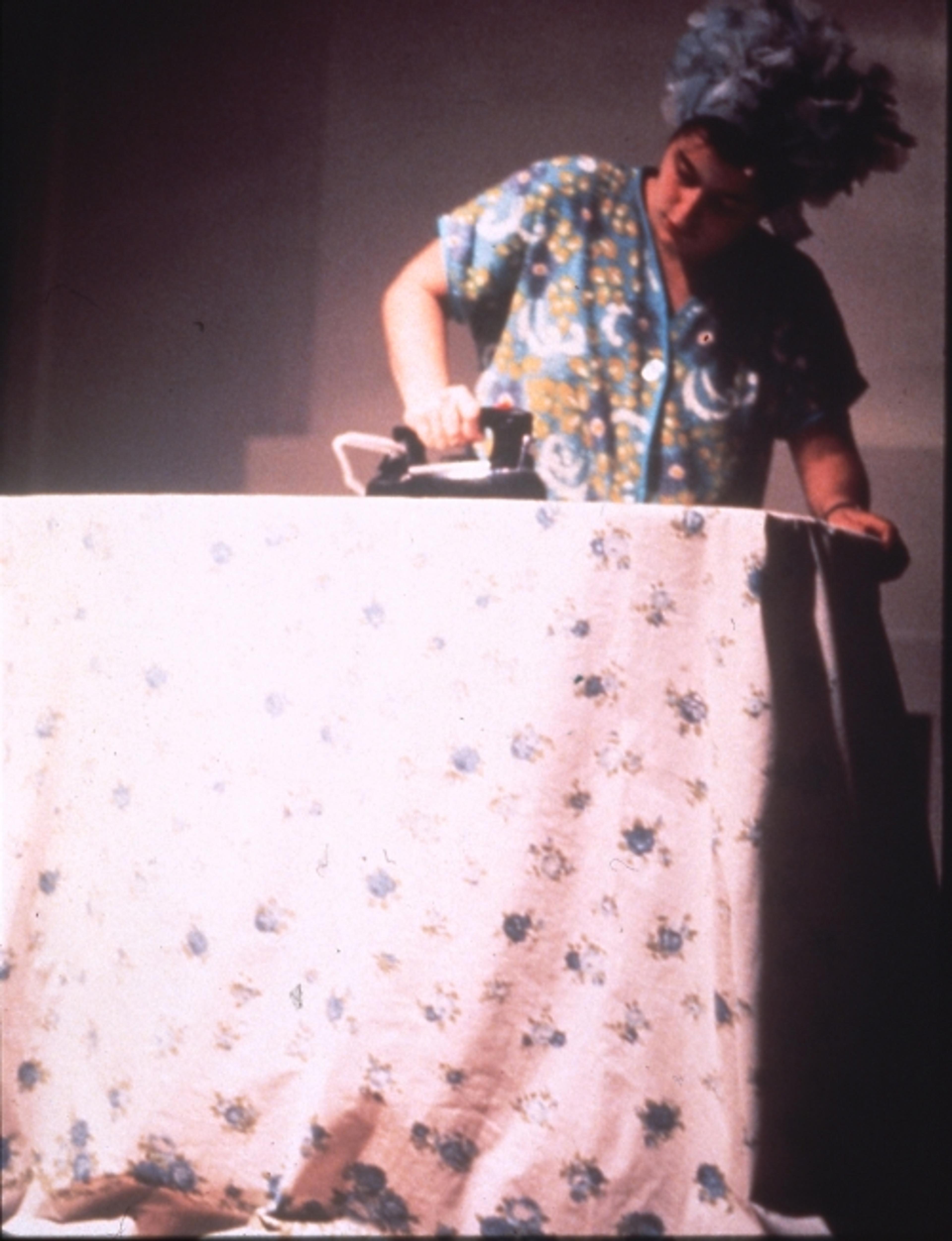

Womanhouse, 1971–72, the large-scale cooperative project executed as part of the Feminist Art Program at CalArts under the direction of Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro, is another such example of feminist artists reclaiming the domestic and “women’s work.” It sought to challenge the traditional roles historically assigned to women in middle-class American society by exploring the subject of women’s labor directly. It was within this inherently domestic environment, or “woman-house,” that 21 women artists were granted space and a voice to present and perform work about stereotypically “feminine” tasks, including scrubbing floors, ironing sheets, cooking, sewing, crocheting, and knitting; cycles, such as menstruation; and forms, such as eggs, breasts, lipstick, and so forth. This landmark exhibition, through its reclamation and use of the domestic-private sphere, takes traditional female experiences as a subject with political and subversive implications.

The Dinner Party should be understood within this context. It is a multi-media work that consists of ceramics, china painting, sewing, needlework, embroidery, and other mediums traditionally associated with “women’s work,” and, as such, not generally considered “high art” by the art world. In an effort to celebrate undervalued female creative production, Chicago consciously sought to reclaim and commemorate those mediums traditionally considered “craft,” as fine art ones equivalent to painting and sculpture. By creating a monumental work of art dedicated to anonymous art by women historically, Chicago thumbed her nose at those who dared to question its artistic value—or the labor involved in its production.

Around the same time that feminist artists were beginning to study mediums and materials associated with “women’s work”—china painting, quilts, sewing, embroidery—they were also searching for a clearly readable means of expressing female subjectivity in abstract forms, which often resembled eggs, spheres, caves, or other round forms. This vaginal or “central core” imagery, as it came to be called, was another important development in 1970s feminist art, one that is integral to understanding The Dinner Party.

Notes

6. Lucy Lippard, From the Center: Feminist Essays on Women’s Art (New York: E.P. Dutton, 1976), 57.

7. Melissa Mayer and Miriam Schapiro, “Waste Not, Want Not: An Inquiry into What Women Saved and Assembled,” Heresies 4 (Winter 1978): 67.

8. Miriam Schapiro, “Notes from a Conversation on Art, Feminism, and Work,” in Working It Out: 23 Women Writers, Artists, Scientists, and Scholars Talk About Their Lives and Work, ed. Sara Ruddick and Pamela Daniels (New York: Pantheon, 1977), 296.

Central Core Imagery

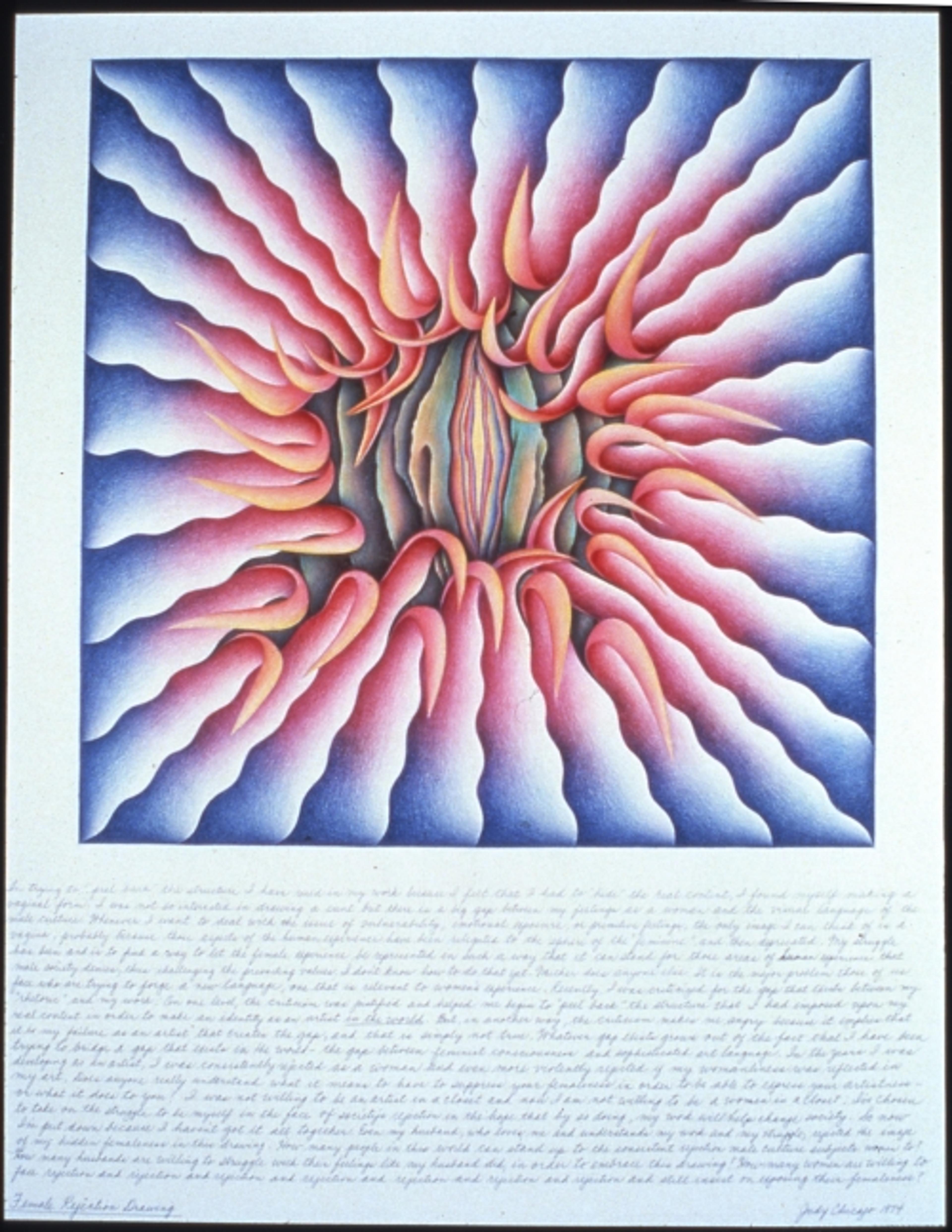

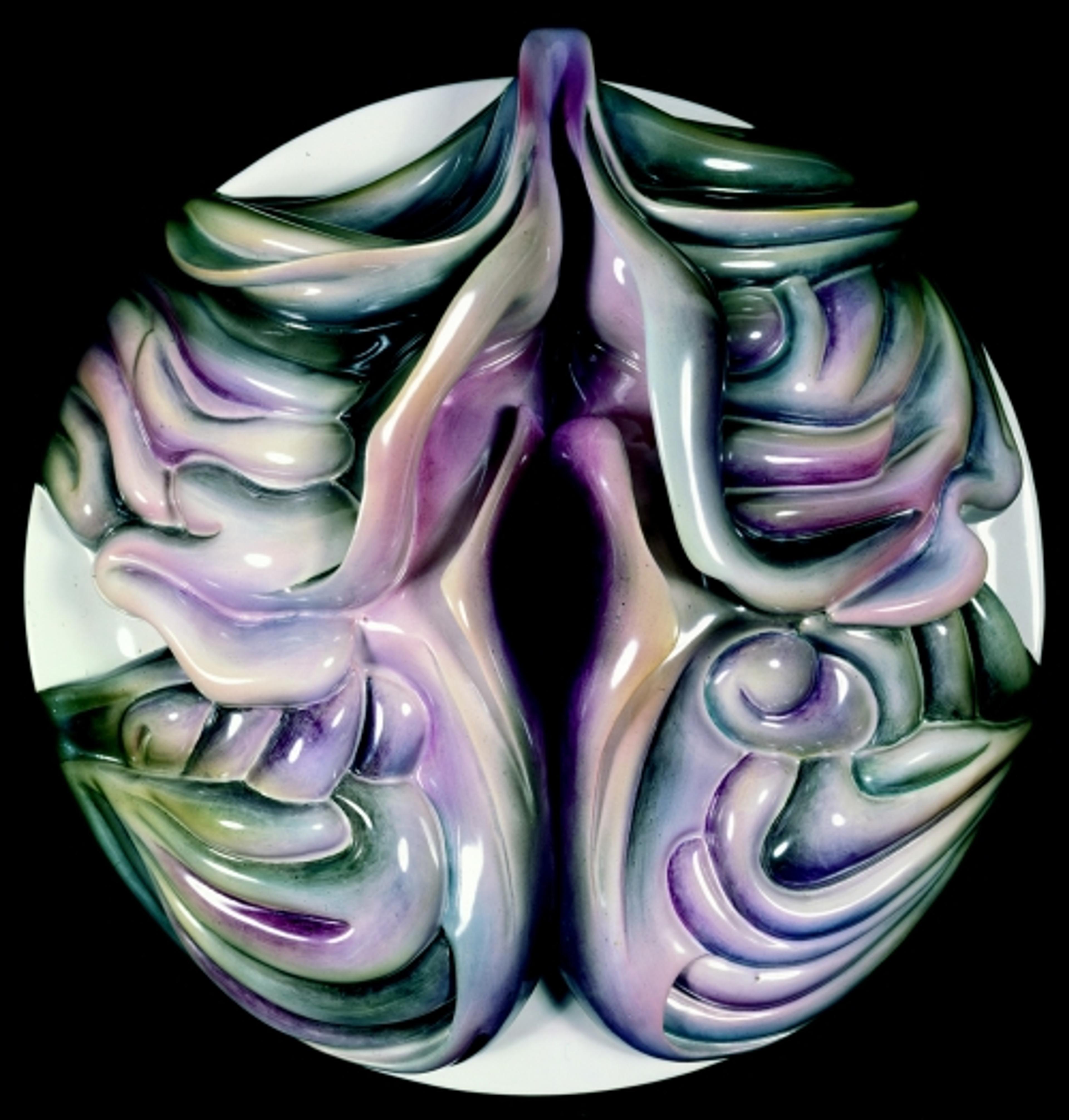

Another feminist strategy encountered in The Dinner Party is the celebration of vaginal iconography, which is, of course, the most controversial of its components. Chicago specifically chose to use vaginal or “central core” imagery for each of the plates in order to demonstrate that the one thing that united these forgotten historical subjects at the table was that they all had the same genitalia. Her aim was to reclaim and celebrate that mark of women’s “otherness,” replacing connotations of inferiority with those of pride, and to create a “new visual language” with which to express women’s experience.

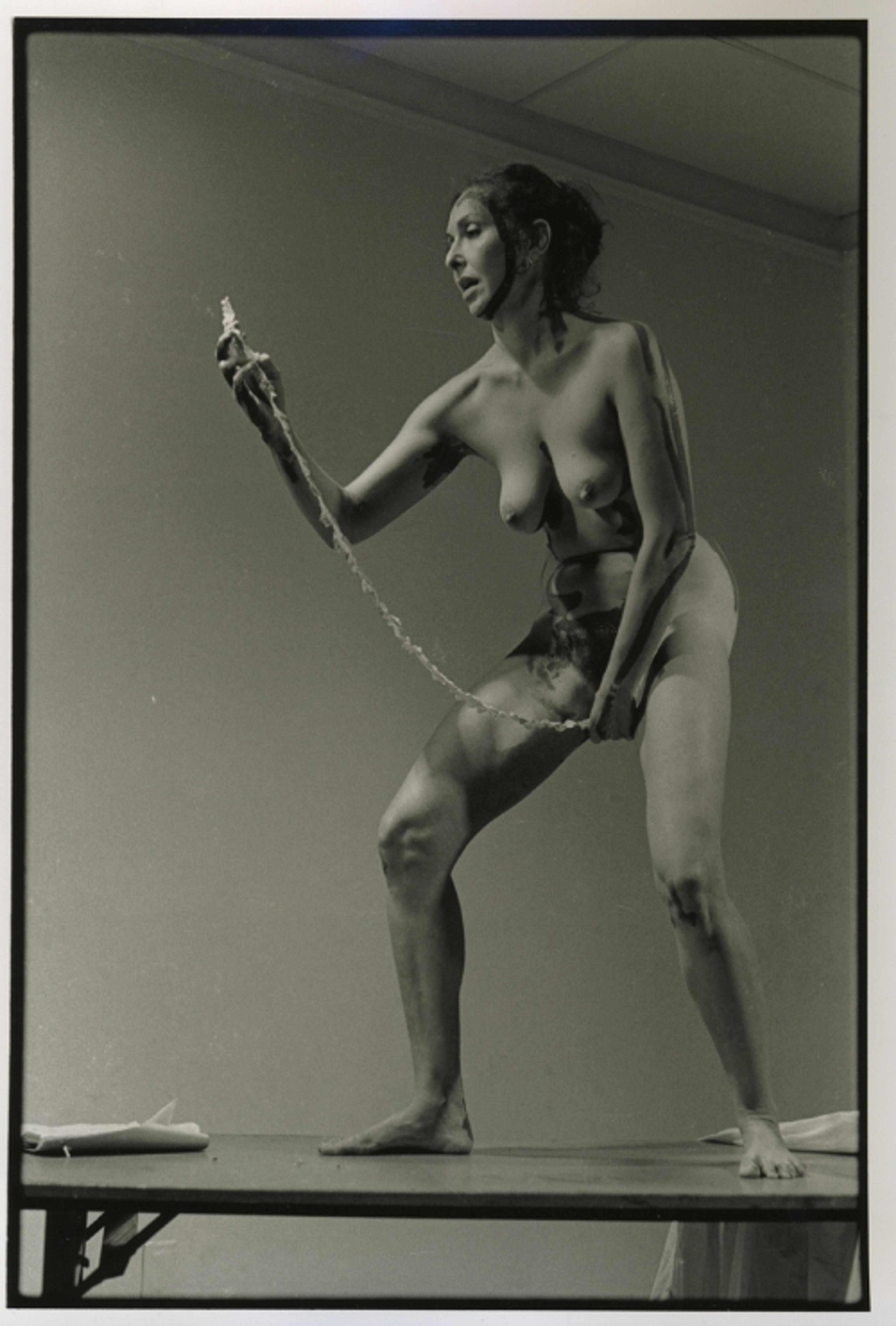

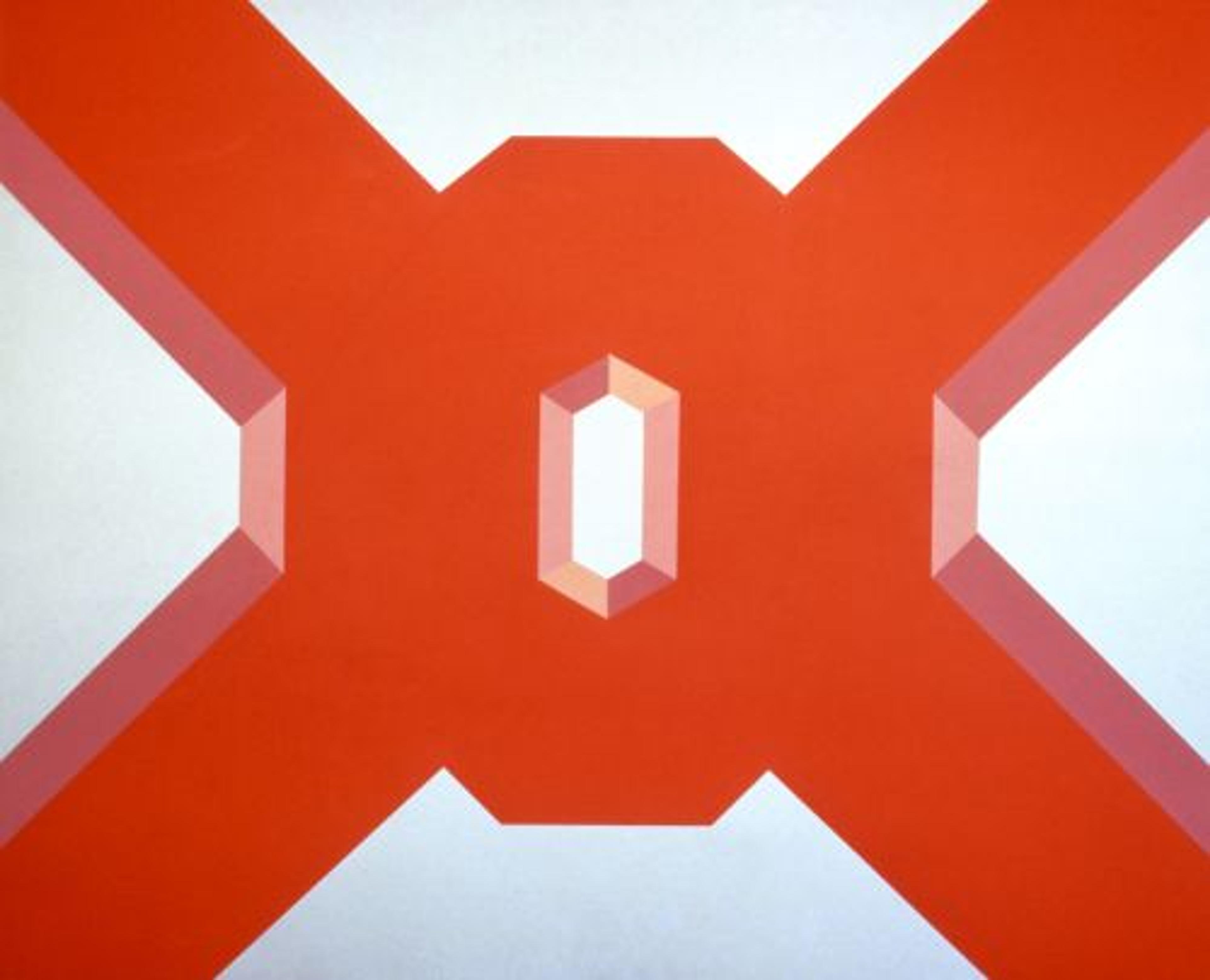

Chicago began experimenting with “central core” imagery in the late 1960s, along with other artists, including Hannah Wilke, Carolee Schneemann, and Miriam Schapiro. Each of these artists, in her own way, sought to give women’s bodies back to them, to assert a positive female sexuality by claiming her sex. Wilke’s miniature gum vagina sculptures that she stuck on her naked body; Schneemann’s interior origami scroll pulled from within her vagina that she read out loud to an audience; and Schapiro’s luscious red Big Ox with its central cavity void all speak to feminist artists’ reclamation of their bodies. The integration and celebration of vaginal imagery at that time was therefore a political gesture, not an erotic one.

Chicago, too, insists that her vaginal imagery be read not literally, but metaphorically, as an active and powerful symbol of female identity. Long before she began work on The Dinner Party, Chicago had been attempting to anthropomorphize the vulvae form, transforming it into numerous motifs suggesting caves and flowers. She eventually fused those abstract “core” images with the butterfly, an ancient symbol of liberation and resurrection, producing “a metaphor for an assertive female identity.”10 She had finally arrived at her signature “central core” form: an active vaginal form, or her equivalent to the flying phallus from Greek art. The imagery of The Dinner Party plates incorporates this butterfly-vulvae motif. Each plate fuses an abstract portrait with an (active) butterfly form. As the visitor circumnavigates the table, the butterfly form surges up dimensionally, symbolizing women’s increased strides toward liberation from prehistory to the modern era.

Notes

9. Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro, “Female Imagery,” Womanspace Journal (1973), 14. (The authors wrote the essay in March 1972.)

10. Chicago, The Dinner Party (New York: Penguin, 1996), 6.

Tour and Home

The Dinner Party first opened to the public at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art on March 14, 1979. Five thousand people attended the opening, and during its three months on view, approximately one hundred thousand people came to see it.

After its premiere, The Dinner Party went on a nine-year international tour sparked by grassroots efforts to find exhibition venues for the piece. The tour began in North America at the University of Houston at Clear Lake, Texas, and continued to venues in Boston, Brooklyn, Cleveland, Chicago, Atlanta, and across Canada. The tour continued through Europe at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe, Scotland; The Warehouse, London; and Schirn Kunsthalle, Frankfurt, Germany; ending at the Royal Exhibition and Conference Center in Melbourne, Australia, in 1988. The exhibitions were hugely popular, drawing large crowds at every venue—for the European tour alone the total viewing audience was over a million people.

During its worldwide tour, The Dinner Party received an enormous amount of press, both positive and negative. Chicago’s desire to create a new visual language with which to express women’s experience and to promote social change by creating respect for women’s history and productions was not well received by the art world at large. Many described the work as “bad art” or “kitsch” without, of course, recognizing Chicago’s deliberate reclamation of “women’s work” as a feminist strategy. Some critics praised the work’s socio-political content; others attacked the “central core” images as literal vaginas rather than metaphoric celebrations of female power.

Several reasons can be deduced from the negative reactions. The most obvious one was the fear of feminism itself. The Women’s Liberation Movement had been, and continued to be, deeply threatening to both women and men. A feminist work of art on this monumental scale with challenging subject matter was bound to provoke controversy.

When the work returned to the U.S. in 1988, it was stored at the National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, D.C., which lacked large enough exhibition space to present it. Plans began to locate a permanent home for the piece, which was a long-time goal for Chicago. To her delight, in 1990, the Trustees of the University of the District of Columbia voted to accept her gift of The Dinner Party for their collection and dedicate funds for its installation in a new gallery in the Carnegie Library. Because Congress controls this University’s budget, however, congresspersons who deemed the piece “pornographic” and “offensive” debated the purchase in televised congressional proceedings and a controversy ensued questioning the “value system” the artwork demonstrated. Ultimately, the acquisition was denied.

The Dinner Party returned to storage until 1996, when it was exhibited at the Armand Hammer Museum at UCLA in the exhibition Sexual Politics: Judy Chicago’s Dinner Party in Feminist Art History, curated by Amelia Jones. It once again drew large crowds, and virulent criticism. After the Sexual Politics exhibition, The Dinner Party returned to storage to face its ambiguous future.

Dr. Elizabeth A. Sackler, philanthropist and board member of the Brooklyn Museum, began discussing the possibility of the Center with Museum director Arnold Lehman and Museum staff. In 2002, the Elizabeth A. Sackler Foundation purchased The Dinner Party, gifting it to the Museum; the artwork was presented as a special exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum where 80,000 people came to see it.

In March 2007, The Dinner Party was permanently installed as the central work in the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art, around which changing exhibitions of feminist art are presented. Situated as such, the Center has thus preserved for posterity a visual symbol that the artist created specifically “to end the ongoing cycle of omission in which women were written out of the historical record.”11

The Dinner Party has found its home.

—Maura Reilly

Founding curator

Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art

Brooklyn Museum

Notes

11. Ibid, 3.