Feminist Art

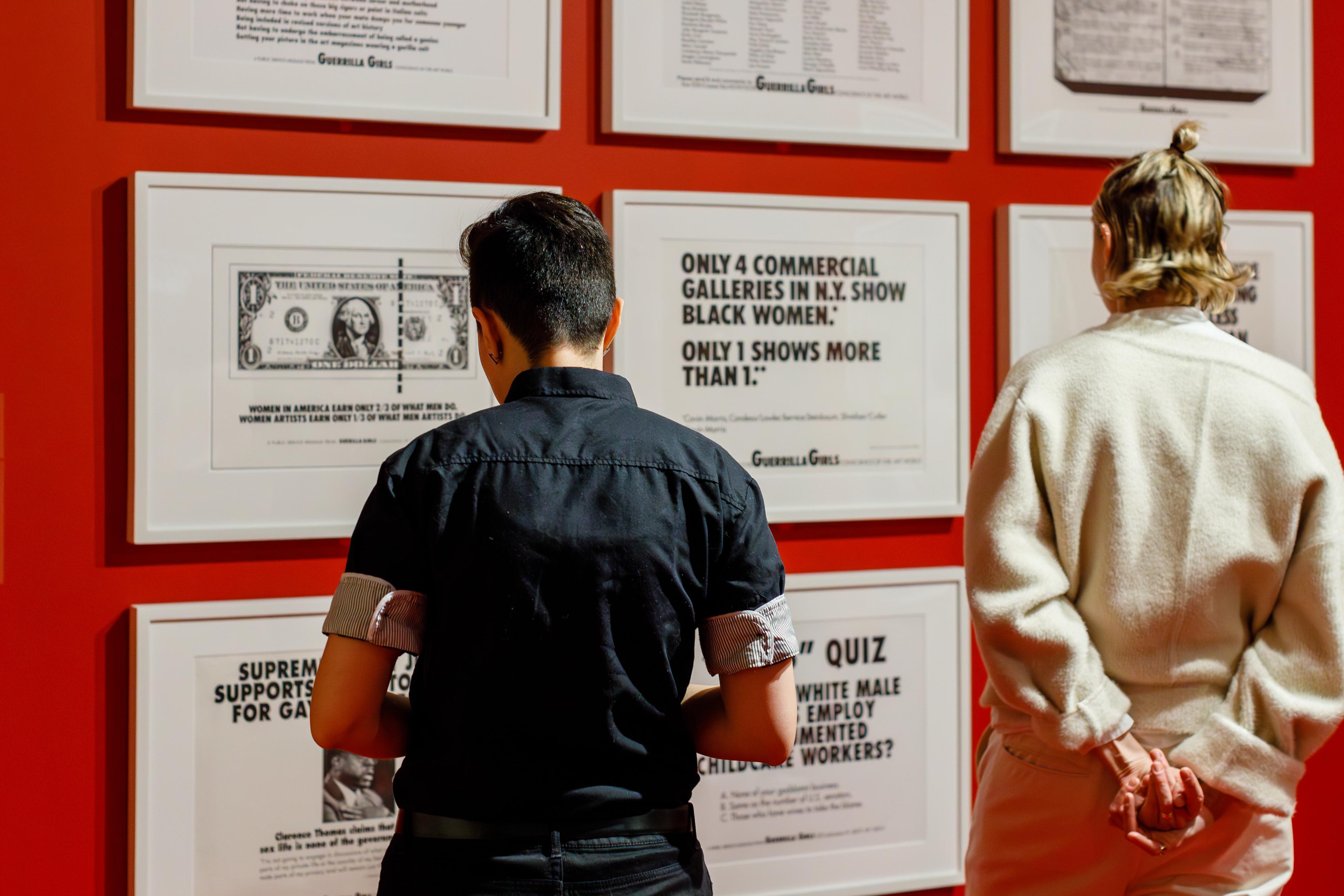

Among the most ambitious, influential, and enduring artistic movements to emerge in the late 20th century, feminist art has played a leading role in the art world over the last 60 years. The movement dramatically redefined art to be more inclusive in both subject matter and medium. Feminist art also revived socially relevant issues after an era of aesthetic formalism, while also pioneering the use of performance and audiovisual media within fine art.

Feminism and feminist art are integral to the Brooklyn Museum’s mission. Our exhibition history is replete with landmark shows dedicated to feminist art and artists. Since 2007, the Museum is proud to be home to the Center for Feminist Art, the only curatorial center of its kind. Our Feminist Art collection is second to none and includes Judy Chicago’s iconic The Dinner Party.

The Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art

About the Center

The Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art is an exhibition and education space dedicated to exploring the myriad ways feminism has and will continue to influence and change visual culture. The center’s mission is to raise awareness of feminism’s cultural contributions, educate new generations about the significance of feminist art, maintain a dynamic and welcoming learning facility, and present feminism in an approachable and relevant way.

The Center for Feminist Art regularly acquires artworks that speak to its mission. Focusing on contemporary and modern work from all over the world, the collection includes objects dating from the early 20th century onward.

The center encompasses approximately 8,300 square feet for changing exhibitions, a space for public programs and educational reflection, and a gallery devoted to The Dinner Party.

History

The Center for Feminist Art was established in 2007 through the generosity of the Elizabeth A. Sackler Foundation, but feminist curatorial approaches and inclusive teaching methods at the Brooklyn Museum can be traced back decades.

In 1971, a public forum titled “Are Museums Relevant to Women?” was held at the Museum. The event, cochaired by artist and activist Faith Ringgold and writer Patricia Mainardi, featured 29 speakers who addressed systemic failures to support women artists and visitors and demanded that museums do better.

In 1980–81, Judy Chicago’s The Dinner Party was presented at the Brooklyn Museum—one of only two fine art museums to participate in the landmark feminist installation’s world tour. In 2002, the Museum acquired the artwork and again put it on temporary display. Five years later, the Center for Feminist Art opened on the Museum’s fourth floor as a public space for exhibitions and convening, with The Dinner Party at its center.

During almost 20 years as part of the institution, the center has hosted dozens of exhibitions and hundreds of public programs. It continues to acquire artworks that exemplify and expand the definition of feminism(s) as an international driver of social change.

Elizabeth A. Sackler

Elizabeth A. Sackler is a public historian, social activist, and American Indian advocate. Dr. Sackler is the CEO and President of the Arthur M. Sackler Foundation and the founder of the American Indian Ritual Object Repatriation Foundation, and she sat on the Brooklyn Museum’s Board of Trustees for 16 years. In 2014 she became Chairman of the Board of Trustees—the first time a woman has held this role since the Brooklyn Museum’s founding in 1823.

Dr. Sackler lectures at universities and colleges in Manhattan, most recently at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice and the Stern School of Business at New York University. As a panelist for ArtTable at the National Museum of the American Indian, NYC, “Understanding the Current Art and Cultural Property Debate and its Impact on the Art World” and at the Vera List Center for Arts and Politics, “Cultural Genocide and Hegemony: Keys to Political, Economic, Religious, and Cultural Domination,” Dr. Sackler addressed historic and current cultural genocide and the legal, ethical, and moral debates raging in the museum and art-market worlds. She has authored numerous articles for scholarly journals and national magazines; her paper “Calling for a Code of Ethics in the Indian Art Market” is in the recently published anthology Ethics and the Visual Arts (Eds. Levin/King, New York: Allworth Press, 2006). She is a regular guest lecturer at the New York University Gallatin School of Individualized Study Graduate Seminar Program.

As President of the Elizabeth A. Sackler Foundation, Dr. Sackler was responsible for giving Judy Chicago’s iconic feminist masterpiece, The Dinner Party, to the Brooklyn Museum in 2002, and for its permanent installation venue in the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art at the Brooklyn Museum, opening March 23, 2007. Through this endeavor, Dr. Sackler has realized her vision to highlight women’s contributions in all fields throughout history, bring feminist art to New York’s major cultural institution, and create a fertile space for feminists, artists, thinkers, and writers to congregate and share ideas and ideals.

Dr. Sackler was honored in 1999 by the Yurok Tribal Council, received the Brooklyn Museum Community Committee Women in the Arts Award in 2002, was one of Women’s eNews “21 leaders of the 21st Century” in 2003, was the recipient of the President’s Award from the Women’s Caucus for Art in 2004, was named “Native American of the Year” by Drums Along the Hudson in 2005, and in April 2006 received ArtTable’s prestigious 2006 Distinguished Service to the Visual Arts.

Highlights

Related exhibitions

Stories and resources

- Story

The Dinner Party Today: Conversations on a Landmark Feminist Work

By: Corinne SegalIntroducing a new podcast from the Brooklyn Museum.

- Video

Reclaimed | Nona Faustine: White Shoes

Nona Faustine joins us from the Lefferts Historic House, a historic homestead in Prospect Park, to discuss sites across New York City that are built upon legacies of enslavement—the focus of her photographic series White Shoes.

- Resource

Teen Guide to Feminist Art

Council for Feminist Art

Join a community as passionate as you are about feminist art. Members meet with curators, attend exhibition openings, participate in annual meetings, and view cutting-edge work in artists’ studios and galleries year-round.

In This Collection Area

Self Portrait as Marcus Fisher I, from the "Portrait of Marcus Fisher I-IV" series

Oreet Ashery

Testimony

He Chengyao

With Blue Clouds and Laughter

Melanie Manchot

Mahuika, from the "Digital Marae" series

Lisa Reihana

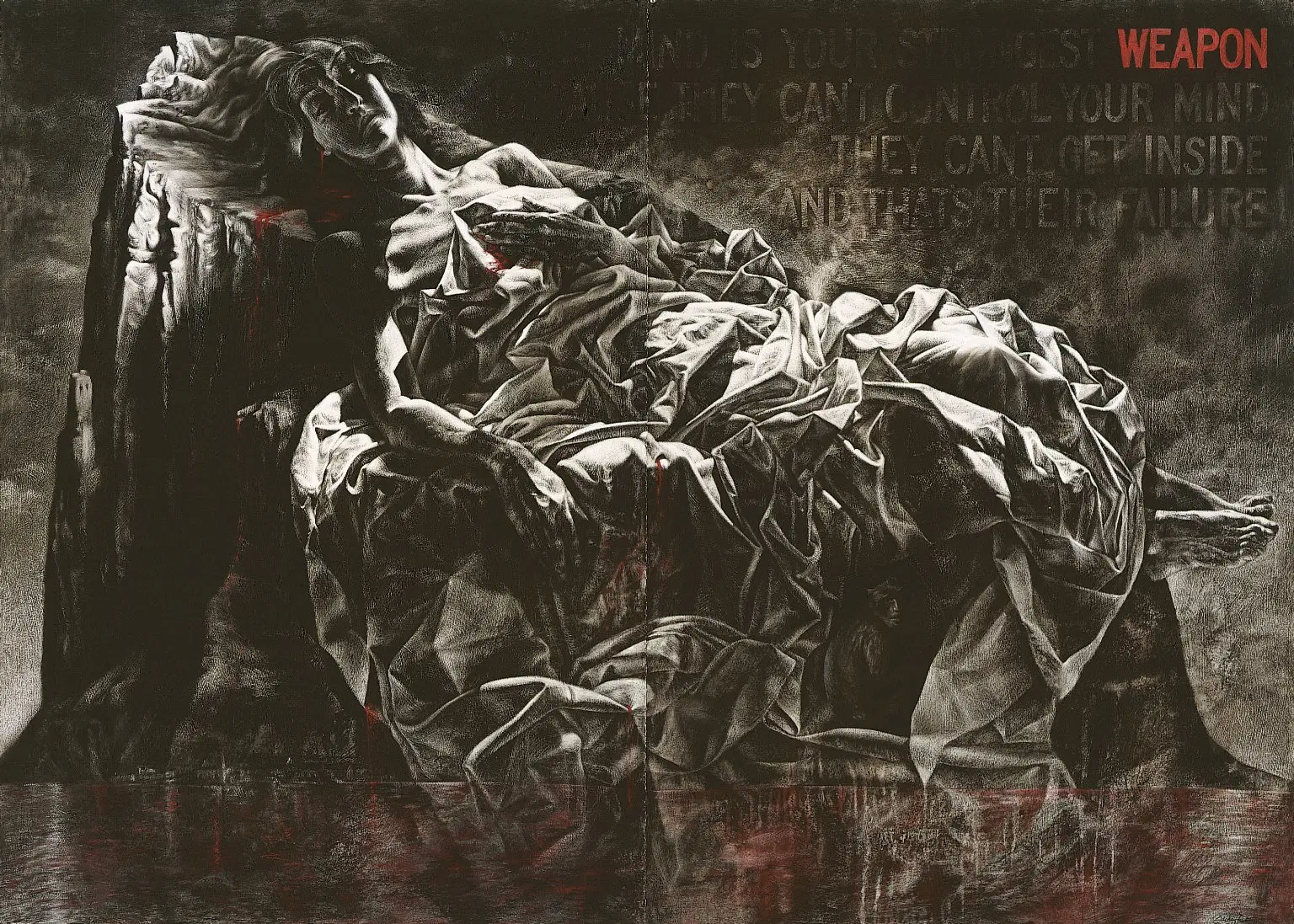

The Hard Place (For Mairead Farrell)

Bailey Doogan

Untitled (Guanaroca [First Woman])

Ana Mendieta

Large Dome Drawing #4

Judy Chicago

Is the Danger Drawing Nearer or Receeding, Six Views from the Womantree

Judy Chicago

Micrographic Study for Pink Triangle/Torture

Judy Chicago

Micrographic Study for Pink and Black Lesbian Triangle

Judy Chicago

99 Needles

He Chengyao

Celebrating the Next Twinkling

Boryana Rossa