Nobody Promised You Tomorrow: Art 50 Years After Stonewall

1 of 10

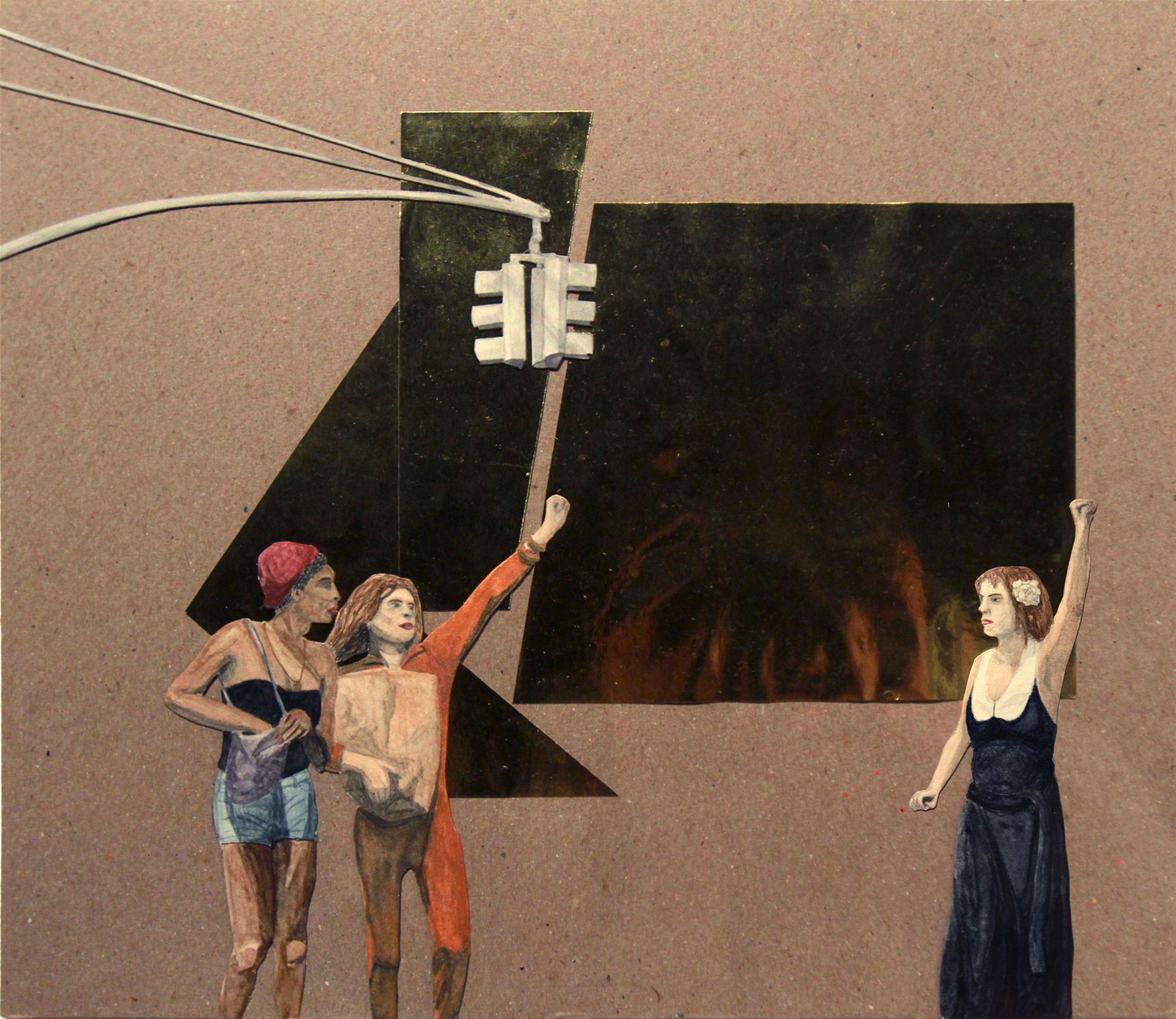

Nobody Promised You Tomorrow: Art 50 Years After Stonewall commemorates the fiftieth anniversary of the 1969 Stonewall Uprising—a six-day clash between police and civilians ignited by a routine raid on the Stonewall Inn, a gay bar in New York City—and explores its profound legacy within contemporary art and visual culture today. The exhibition draws its title from the rallying words of transgender artist and activist Marsha P. Johnson, underscoring both the precariousness and the vitality of LGBTQ+ communities.

The exhibition presents twenty-eight LGBTQ+ artists born after 1969 whose works grapple with the unique conditions of our political time, and question how moments become monuments. Through painting, sculpture, installation, performance, and video, these artists engage interconnected themes of revolt, commemoration, care, and desire.

The exhibition includes Mark Aguhar, Felipe Baeza, Morgan Bassichis, Anna Betbeze, David Antonio Cruz, TM Davy, Amaryllis DeJesus Moleski, John Edmonds, Mohammed Fayaz, Camilo Godoy, Jeffrey Gibson, Hugo Gyrl, Juliana Huxtable, Rindon Johnson, DonChristian Jones, Papi Juice, Elektra KB, Linda LaBeija, Park McArthur, Michi Ilona Osato, Una Aya Osato, Elle Pérez, LJ Roberts, Tuesday Smillie, Tourmaline, Kiyan Williams, Sasha Wortzel, and Constantina Zavitsanos. This exhibition also transforms the Forum space within the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art into an interactive Resource Room for visitors to engage LGBTQ+ histories and connect with local resources and community organizations working today.

Nobody Promised You Tomorrow: Art 50 Years After Stonewall is curated by Margo Cohen Ristorucci, Public Programs Coordinator; Lindsay C. Harris, Teen Programs Manager, Education; Carmen Hermo, Associate Curator, Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art; Allie Rickard, Curatorial Assistant, Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art; and Lauren Argentina Zelaya, Acting Director, Public Programs, Brooklyn Museum. Its Resource Room is organized by Levi Narine, Teen Programs Assistant, InterseXtions and Special Projects, in collaboration with the curators.

Generous support for this exhibition is provided by The Kaleta A. Doolin Foundation. Additional support provided by Paul R. Beirne, the Helene Zucker Seeman Memorial Exhibition Fund, Robert Shiell Collection, Sally Susman and Robin Canter, and MaryRoss Taylor.

The Keith Haring Foundation and Blanchette Hooker Rockefeller Fund provided generous support for related Education programming.

Organizing department

Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art