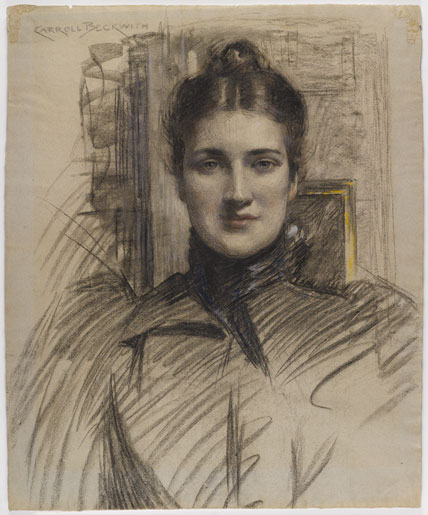

J. Carroll Beckwith (American, 1852–1917). Portrait of Minnie Clark, 1890s. Charcoal and pastel on blue fibered laid paper, 223⁄8 x 181⁄4 in. (56.8 × 46.4 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Gift of J. Carroll Beckwith, 17.127

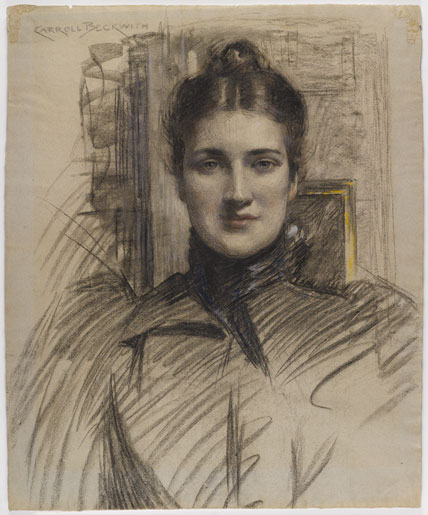

J. Carroll Beckwith (American, 1852–1917). Portrait of Minnie Clark, 1890s. Charcoal and pastel on blue fibered laid paper, 223⁄8 x 181⁄4 in. (56.8 × 46.4 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Gift of J. Carroll Beckwith, 17.127

Edward Hopper (American, 1882–1967). Male Nude, circa 1903–4. Graphite and charcoal on cream paper, 24 × 95⁄8 in. (61 × 24.4 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Morton Ostrow, 82.253.2

Edward Hopper invested this drawing with a bold frankness and palpable sense of realism that came from working from the live model in a class at the New York School of Art taught by Robert Henri, an influential teacher and leader of the Ashcan School of urban Realists. Hopper’s skills of close observation are evident in the model’s air of boredom as he holds the pose. The angled forms in the background suggest the tilted easels of other students, while the tiny sketch of a female nude at the upper right injects a note of bawdy humor. Hopper’s graphic talents earned him a teaching position at the school in 1905 and, subsequently, a successful early career as an illustrator.

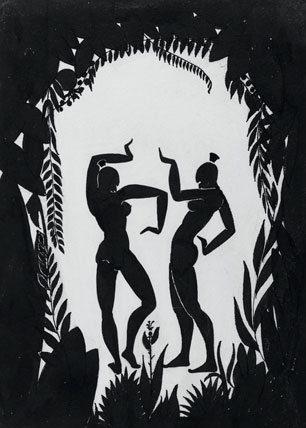

Richard Bruce Nugent (American, 1906–1987). Dancing Figures, circa 1935. Black ink and graphite on cream wove paper, 143⁄4 x 101⁄2 in. (37.5 × 26.7 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Dr. Thomas H. Wirth, gift of Frederick J. Adler, by exchange, bequest of Richard J. Kempe, by exchange, and gift of Abraham Walkowitz, by exchange, 2008.50.6. © Thomas H. Wirth

A dancer and performer himself, Richard Bruce Nugent had a deep affinity for the expressive possibilities of the human body in motion. In this striking image, he depicted dancers and plants as flat, stylized forms rendered in black silhouettes. In the mid-1920s, inspired in part by African art, several artists of the Harlem Renaissance embraced a silhouette aesthetic. As suggested in a verse of Nugent’s poem “Shadow” (1925), the silhouette also had personal significance for the artist, who was African American:

Silhouette A silhouette am I On the face of the moon Lacking color Or vivid brightness But defined all the clearer Because I am dark Black on the face of the moon.

Winslow Homer (American, 1836–1910). The Unruly Calf, circa 1875–76. Graphite and white opaque watercolor on blue-gray wove paper, 411⁄16 x 81⁄2 in. (11.9 × 21.6 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Museum Collection Fund, 24.241

This deftly executed preparatory drawing for a painting is one of several works that Winslow Homer created about 1875 depicting an African American boy engaged in a tug-of-war of wits and brawn with a calf. A faint outline indicates that the artist experimented with the position of the calf’s tail before settling on a final pose expressive of the animal’s indignation.

Homer’s images were praised by contemporary critics for their sympathetic and naturalistic treatment of blacks—a striking departure from the racist caricatures that proliferated in nineteenth-century visual culture. While rural children were a favorite subject of the artist, this particular work could also be a metaphor for the struggles of African Americans for self-determination during Reconstruction.

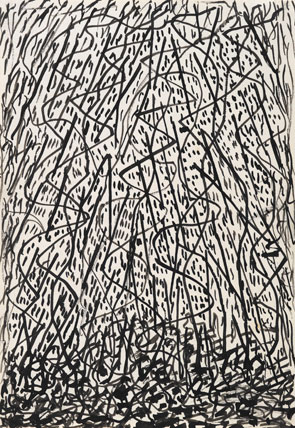

Abraham Walkowitz (American, b. Siberia, 1878–1965). Improvisations of New York, 1914. Ink on paper mounted to backing paper, 101⁄2 x 71⁄4 in. (26.7 × 18.4 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Bequest of Mrs. Carl L. Selden, 1996.157.31

Executed at a time when Abraham Walkowitz was experimenting with modernist abstraction, Improvisations of New York captures the frenetic energy of the city through the dynamic handling of the ink. Angled and squiggled lines evoke the vertical thrust of skyscrapers soaring above the crowded street, suggested by a denser concentration of strokes at the bottom of the composition.

Max Weber (American, b. Russia, 1881–1961). Composition with Four Figures, 1910. Charcoal and pastel on laid paper, 241⁄4 x 181⁄4 in. (61.6 × 46.4 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Dick S. Ramsay Fund, 57.17

One of the first American artists to embrace modernist innovations in European art, Max Weber created this drawing after a sojourn in Paris from 1905 to 1908. The blocky forms, faceted planes, and masklike faces of his figures show the influence of the early Cubism of Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, both of whom Weber met in Paris.

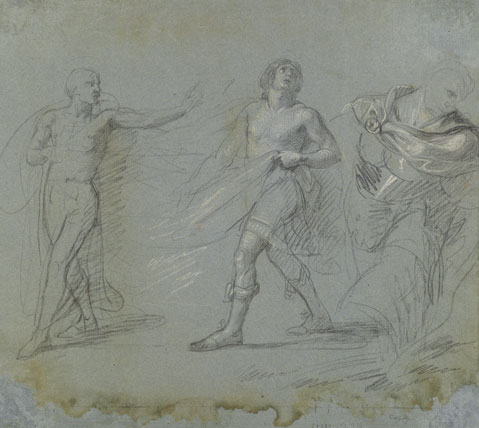

John Singleton Copley (American, 1738–1815). Studies for “Saul Reproved by Samuel in Not Obeying the Commandments of the Lord,” 1797–98. Black crayon and white chalk on blue laid paper, 121⁄4 x 141⁄4 in. (31.1 × 36.2 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Purchased with funds given by Mr. and Mrs. Leonard L. Milberg, 1990.126.1a–b

John Singleton Copley regularly made preparatory drawings for his complex, multifigural paintings in the Grand Manner. This double-sided sheet of figure studies provides a fascinating glimpse into Copley’s creative process as he experimented with poses and costumes for a biblical narrative depicting a dramatic encounter between the prophet Samuel and King Saul. The two highly finished sketches of Samuel’s voluminous drapery are particularly finely modeled with deft strokes of black chalk and highlights of white.

Fine Lines: American Drawings from the Brooklyn Museum

March 8–May 26, 2013

Fine Lines: American Drawings from the Brooklyn Museum presents a selection of over 100 of the finest, rarely seen drawings and sketchbooks from the Museum’s world-renowned collection of American art. Produced between 1768 and 1945 in a wide range of media (including graphite, pen and ink, crayon, charcoal, and pastel), the featured objects represent a variety of iconographies, styles, and practices in the history of American graphic arts. More than seventy artists are represented, including Winslow Homer, Thomas Eakins, John Singer Sargent, Edward Hopper, and Marsden Hartley.

The exhibition is organized into six thematic sections, examining portraiture, nudes, the clothed figure, narrative subjects, and natural and urban environments. It is accompanied by a scholarly catalogue including interpretive essays, illustrated catalogue entries, and a selected bibliography.

Fine Lines: American Drawings from the Brooklyn Museum is organized by Karen Sherry, former Associate Curator of American Art, Brooklyn Museum.

Generous support for this exhibition and the accompanying catalogue was provided by Leonard and Ellen Milberg. Additional funding for the exhibition was provided by the Robert E. Blum Fund. The catalogue was also supported by Linda E. Scher, Furthermore: a program of the J. M. Kaplan Fund, and a Brooklyn Museum publications endowment established by the Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Foundation and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.