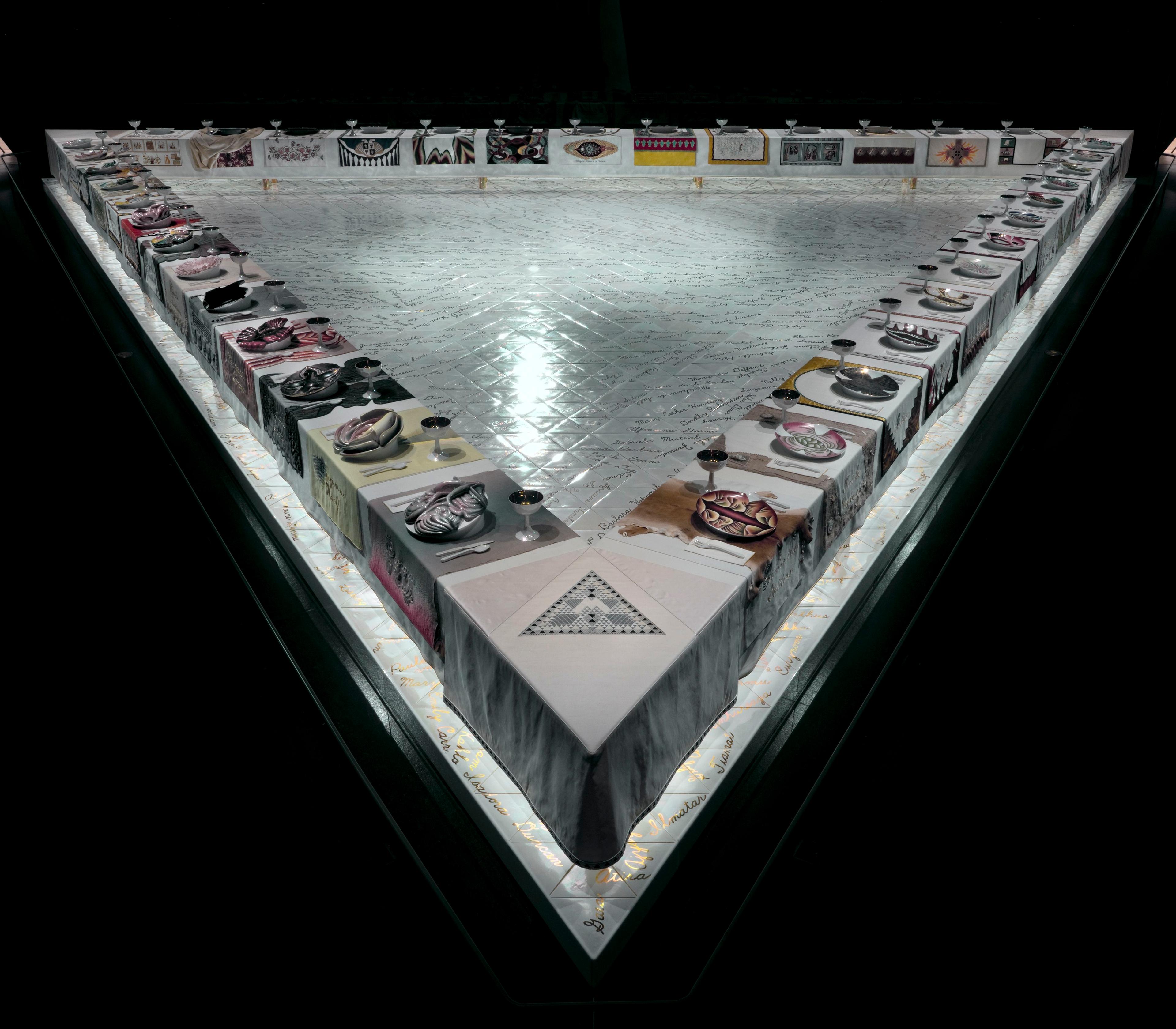

Components of The Dinner Party

The Dinner Party by Judy Chicago, an icon of feminist art, represents 1,038 women in history: 39 women are represented by place settings and another 999 names are inscribed in the Heritage Floor on which the table rests. This monumental work of art comprises a triangular table divided by three wings, each 48 feet long.