Christine de Pisan

(b. 1364, Venice, Italy; d. 1430, Poissy, France)

Christine de Pisan (Christine de Pizan) was a medieval writer and historiographer who advocated for women’s equality. Her works, considered to be some of the earliest feminist writings, include poetry, novels, biography, and autobiography, as well as literary, political, and religious commentary. De Pisan became the first woman in France, and possibly Europe, to earn a living solely by writing.

De Pisan was raised at court in Paris with her father, Thomas de Pisan, the astrologer and secretary to King Charles V of France. Although her educational upbringing is unclear, through her father’s court appointment, she did have access to a variety of exceptional libraries. In 1380, de Pisan married Etienne du Castel, a nobleman from Picardy. He was an unusual husband for the time in that he supported her educational and writing endeavors. When he died in 1390, de Pisan was only in her early twenties. After receiving attention from patrons in the court for her poetry and love ballads dedicated to her husband, she decided that rather than remarry she would support her three children and newly widowed mother through her writing. While she was still establishing herself as a writer, de Pisan also transcribed and illustrated other authors’ works.

Her own writing, in its various forms, discusses many feminist topics, including the source of women’s oppression, the lack of education for women, different societal behaviors, combating a misogynistic society, women’s rights and accomplishments, and visions of a more equal world. De Pisan’s work, though critical of the prevailing patriarchy, was well received, as it was also based in Christian virtue and morality. Her writing was especially strong in rhetorical strategies that have since been extensively studied by scholars.

Her two most famous works are the books Le Dit de la Rose (The Tale of the Rose), 1402, and Le Tresor de la Cité des Dames (The Book of the City of Ladies), 1405. Le Dit de la Rose was a direct attack on Jean de Meun’s extremely popular Romance of the Rose, a work about courtly love that characterized women as seducers, which de Pisan claimed was misogynistic, vulgar, immoral, and slanderous to women. She later published Letters on the Debate of the Rose as a follow-up to the controversial debate.

In Le Tresor de la Cité des Dames, de Pisan has a discussion with three “ladies,” introduced as Reason, Rectitude, and Justice, about the oppression of women and the misogynistic subject matter and language that contemporary male writers used. Under the author’s guidance, the women form their own city, where only women of virtue reside. In the book, she writes, “Moreover, it is just as applicable to ladies, maidens, and other women to have worldly prudence in regulating their lives well, each according to her estate, and to love honour and the blessings of a good reputation” (Lawson, trans., The Treasure of the City of Ladies, 110).

Although de Pisan’s work was primarily written for and about the upper classes (the majority of lower class women were illiterate), her writing was instrumental in introducing the concept of equality and justice for women in medieval France. De Pisan lived the majority of her life in relative comfort, and in 1418, she entered a convent in Poissy (northwest of Paris), where she continued to produce work, including her last poem Le Ditie de Jeanne d’Arc (Song in Honor of Joan of Arc), 1429.

Christine de Pisan at The Dinner Party

Christine de Pisan is represented in her plate as an abstracted butterfly form painted in swirling, vibrant hues of red and green. Chicago describes the form as having “one wing raised in a gesture of defense, to symbolize her efforts to protect women” (Chicago, The Dinner Party, 86).

The runner is done in tones from the same color palette, and jagged flame-like forms adorn the edges. The wavy, colorful pattern is characteristic of Bargello needlepoint, also called “flame stitch” or “Florentine stitch,” thought to have originated in medieval Italy. According to Chicago, this design, which appears to be encroaching on the plate, represents the suffocating Renaissance-era constraints on women (Chicago, The Dinner Party, 86).

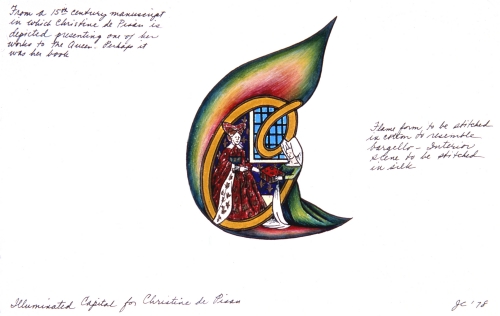

On the front of the runner, embroidered on the illuminated capital “C” in her name, is a scene based on an illuminated manuscript in which de Pisan presents a volume of her work to the queen of France. This book represents her writing as a gift of knowledge and feminism that was offered to the medieval world.

Primary Sources

L’epistre au dieu d’amours (Letter of the God of Love or Cupid’s Letter), 1399.

Le debat deux amants (The Debate of Two Lovers), 1400.

Le livre des trois jugemens (The Book of Three Judgments), 1400.

Le livre du dit de poissy (The Tale of Poissy), 1400.

Enseignemens moraux et proverbes moraux (Moral Teachings and Moral Proverbs), 1400.

Epitre d’Othea (Othea’s Letter or Epistle of Othea to Hector), 1400.

Epistres du debat su le roman de la rose (Letters on the Debate Concerning the Romance of the Rose), 1401–03.

Cent ballades d’amant et de dame, virelyas, rondeaux (One Hundred Ballades of a Lover and His Lady), 1402.

Le dit de la rose (The Tale of the Rose), 1402.

Livre du chemin de long estude (The Book of the Road of Long Learning), 1403.

Le livre de la mutacion de fortune (The Mutation of Fortune), 1403.

Livre des fais et bonnes meurs du sage Roi Charles V (The Book of the Deeds and Good Customs of the Wise King Charles V), 1404.

Le livre du duc des vrais amants (The Book of the Duke of True Lovers), 1405.

Le livre de la cité des dames (The Book of the City of Ladies), 1405.

Livre de trois vertus or Le tresor de la cité des dames (The Book of Three Virtues or The Book of the Treasury of Ladies), 1405.

Avision-Christine or L’avision (Christine’s Vision), 1405.

Livre du corps de policie (The Book of the Body Politic), 1407.

Sept psaumes allegorises (Seven Allegorized Psalms), 1410.

Le livre des fais d’armes et de chevalerie (The Book of the Deeds of Arms and Chivalry), 1410.

Livre de la paix (The Book of Peace), 1414.

Le ditie de Jeanne d’Arc (Song in Honor of Joan of Arc), 1429.

Translations, Editions, and Secondary Sources

Brabant, Margaret. Politics, Gender and Genre: The Political Thought of Christine de Pizan. Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press, 1992.

Brown-Grant, Rosalind. Christine de Pizan and the Moral Defense of Women: Reading Beyond Gender. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

Hindman, Sandra. Christine de Pizan’s “Epistre Othéa”: Painting and Politics at the Court of Charles VI. Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies, 1986.

Hopkins, Andrea. Most Wise and Valiant Ladies. New York: Welcome Rain, 1997.

Lawson, Sarah, trans. The Treasure of the City of Ladies, by Christine de Pizan. New York: Penguin, 1985.

McLeod, Enid. The Order of the Rose: The Life and Ideas of Christine de Pizan. London: Chatto and Windus, 1976.

Pemoud, Régine. Christine de Pisan. Paris: Calmann-Lévy, 1982.

Quilligan, Maureen. The Allegory of Female Authority: Christine de Pizan’s Cité des Dames. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1991.

Willard, Charity-Cannon. Christine de Pizan: Her Life and Works. New York: Persea Books, 1984.

Yenal, Edith. Christine de Pisan: A Bibliography of Writings By Her and About Her. Metuchen, N.J.: Scarecrow Press, 1982.

Zimmermann, Margarete, and Dina De Rentiis. The City of Scholars: New Approaches to Christine de Pizan. New York: Gruyter, 1994.

Judy Chicago (American, b. 1939). The Dinner Party (Christine de Pisan place setting), 1974–79. Mixed media: ceramic, porcelain, textile. Brooklyn Museum, Gift of the Elizabeth A. Sackler Foundation, 2002.10. © Judy Chicago. Photograph by Jook Leung Photography

Place Setting Images

Judy Chicago (American, b. 1939). The Dinner Party (Christine de Pisan plate), 1974–79. Porcelain with overglaze enamel (China paint), 14 × 14 × 1 3/16 in. (35.6 × 35.6 × 3 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Gift of the Elizabeth A. Sackler Foundation, 2002.10. © Judy Chicago. (Photo: © Donald Woodman)

Judy Chicago (American, b. 1939). The Dinner Party (Christine de Pisan runner), 1974–79. Cotton/linen base fabric, woven interface support material (horsehair, wool, and linen), cotton twill tape, silk, synthetic gold cord, canvas, wool yarn, thread, 51 3/4 × 30 1/8 (131.4 × 76.5 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Gift of the Elizabeth A. Sackler Foundation, 2002.10. © Judy Chicago

Biographical Images

Related Heritage Floor Entries

- Agnes of Dunbar

- Aliénor de Poitiers

- Anastasia (Christine de Pisan group)

- Angela Merici

- Beatrix Galindo

- Bourgot

- Clara Hatzerlin

- Cobhlair Mor

- Francisca de Lebrija

- Ingrida

- Isotta Nogarola

- Jane Anger

- Juliana Bernes

- Maddalena Buonsignori

- Margaret Beaufort

- Margaret O’Connor

- Margaret Paston

- Margaret Roper

- Margareta Karthauserin

- Margery Kempe

- Martha Baretskaya

- Modesta Pozzo

- Rose de Burford

- Teresa de Cartagena